Course Authors

Lona Mody, M.D., M.Sc.

Dr. Mody is an Assistant Professor, University of Michigan Medical School, and Associate Director, Clinical Programs, at the Ann Arbor VA Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Within the past 12 months, Dr. Mody reports no commercial conflicts of interest.

Estimated course time: 1 hour(s).

Albert Einstein College of Medicine – Montefiore Medical Center designates this enduring material activity for a maximum of 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

In support of improving patient care, this activity has been planned and implemented by Albert Einstein College of Medicine-Montefiore Medical Center and InterMDnet. Albert Einstein College of Medicine – Montefiore Medical Center is jointly accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME), the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE), and the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC), to provide continuing education for the healthcare team.

Upon completion of this Cyberounds®, you should be able to:

Describe risk factors and epidemiology of common infections in long-term care facility residents

List diagnostic criteria for infections in patients with a paucity of symptoms

Implement strategies to prevent common infections in long-term care facility residents.

Healthcare delivery in the United States has evolved dramatically over the last two decades. Previously, healthcare occurred primarily in acute care facilities. Today, it is delivered in multiple settings including hospitals, sub-acute care, long-term care facilities (LCTFs) or nursing homes, rehabilitation, assisted living, home and outpatient settings.

Efforts to restrain healthcare costs have led to a reduced number of hospitalizations and shorter lengths of stay (with an associated increase in severity of illness and intensive care unit admissions), along with increased outpatient, home care and nursing home stays for older adults.(1) As a consequence, nursing homes and rehabilitation units are seeing sicker patients, who require more intense medical supervision and are more susceptible to infections and antimicrobial resistance (Table 1).

Table 1. Differences Between Acute Care Hospitals and Nursing Homes With Respect to Infection Management.

| Characteristics | Acute Care Hospitals | Nursing Homes |

|---|---|---|

| Patient Population | All ages | Predominantly older adults |

| Overall Goals of patient care | Acute care management, Disease recovery | Predominantly chronic disease management with spurts of acute disease management, Functional recovery and stability |

| Length of stay | Days, weeks | Years |

| Physician visits | Frequent, daily | Infrequent, often monthly |

| Recognition of infection signs | Physicians and nurses | Nurses aides first, followed by nurses and physicians |

| Infection definition | Based on physical findings as well as laboratory | Based on physical findings with limited timely laboratory support |

| Resources for Infection Control | Broad | Very variable, inconsistent |

Infections in LTCFs increase the mortality and morbidity of residents and lead to transfers to acute care hospitals. In fact, each year, a staggering 1.5-2.0 million infections occur in long-term care facilities, resulting in frequent hospital transfers and an estimated 1-2 billion dollars in hospital expenditures.(2)

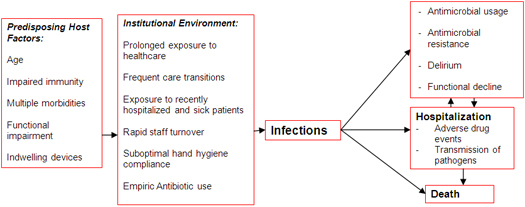

Older adults over the age of 65 account for a disproportionate share of patients with infection-related hospitalizations in the U.S.(3) The hazards of the hospitalization of LTCF residents are numerous and include functional decline, delirium, pressure ulcers and adverse drug events (Figure 1). This Cyberounds® review highlights the epidemiology, diagnosis and prevention of common infections in the long-term care setting.

Figure 1. Pathway to Nursing Home Infections and Antimicrobial Resistance.

Click here to view full image.

Urinary Tract Infections

Urinary tract infection remains the leading nosocomial infection in LTCFs. It is a common cause of bacteremia and often leads to hospital transfers. UTI rates are now considered facility quality indicators and reported quarterly by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS). New symptomatic UTI rates ranged from 0 to 2.3 infections/1000 resident days.(4) UTIs also lead to frequent and often inappropriate antibiotic usage. Asymptomatic bacteriuria occurs in nearly 50% of all LTCF residents.(2)

Risk Factors

Several risk factors can lead to UTIs in this population. These include functional and cognitive impairment, prolonged institutional stay, neurogenic bladder, diabetes and urinary catheter use. Urinary catheters are frequently used for both short- and long-term care in skilled LTCFs.(5)(6)(7) A recent study of all skilled LTCFs in four states showed that 12%-13% of all new admissions had indwelling catheters.(5) Within U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs nursing homes (NHs), 14% of residents have an indwelling urinary catheter.(6) These indwelling catheters carry many risks for NH residents including asymptomatic bacteriuria, symptomatic UTIs and antimicrobial resistance.

The majority of LTCF residents with indwelling urinary catheters have persistent bacteriuria. Indeed, studies have found that over 90% of all LTCF residents with urinary catheters had bacteriuria.(8)(9) Moreover, it is estimated that 50% of LTCF residents with urinary catheters will have symptomatic catheter-associated UTIs each year. Long-term care residents with indwelling catheters are also more likely to have UTIs with multi-drug resistant organisms than residents without these devices.(8)(9)

Diagnostic Signs and Symptoms

Diagnostic criteria for UTIs have been developed for this population.(10) In non-catheterized patients, at least three of the following signs and symptoms should be present:

- fever (>38°C) or chills

- new or increased burning pain on urination, frequency or urgency

- new flank pain, suprapubic pain or tenderness

- change in character of urine

- worsening of mental or functional status.

In catheterized patients, at least two of the following signs or symptoms should be present:

- fever (>38°C) or chills

- new flank pain, suprapubic pain or tenderness

- change in character of urine or

- worsening of mental or functional status (see Table 2).

Table 2. Standardized Surveillance Definitions Used to Detect Infections.

| Infection | Criteria |

|---|---|

| Pneumonia |

Interpretation of chest radiograph as demonstrating pneumonia, probable pneumonia, or presence of an infiltrate. Resident must have at least two of: new or increased cough, new or increased sputum production, fever, pleuritic chest pain, new or increased finding on physical chest exam, change in breathing status or new/increased confusion. |

| Urinary tract infection |

The resident does not have a urinary catheter and has at least three of the following signs and symptoms: (a) fever (>38°C) or chills, (b) new or increased burning pain on urination, frequency or urgency, (c) new flank or suprapubic pain or tenderness, (d) change in character of urine, (e) worsening of mental or functional status. The resident has an indwelling catheter and has at least two of the following signs or symptoms: (a) fever (> 38°C) or chills, (b) new flank or suprapubic pain or tenderness, (c) change in character of urine, (d) worsening of mental or functional status. |

| Skin and soft tissue infection | One of the following criteria must be met: 1. Purulence present at a wound, skin, or soft tissue site. 2. The resident must have four or more of the following signs or symptoms: (a) fever (>38°C) or worsening mental/functional status; and/or, at the affected site, the presence of new or increasing (b) heat, (c) redness, (d) swelling, (e) tenderness or pain, or (f) serous drainage. |

Since urinary tract is the most common source of infection in catheterized patients, the presence of fever and increased confusion or worsening functional status should be treated as a UTI. Although these criteria need further study with respect to their reliability and validity, they are generally well accepted in an LTCF setting. Obtaining a urine culture is important −− not only to identify the infecting organism but also to provide susceptibility to guide effective therapy.

Prevention Guidelines

Research studies show that specific catheter-care practices can reduce the entry of organisms into the usually sterile urinary bladder.(11) These research findings have been translated into recommendations by leading organizations such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to reduce or prevent catheter-associated disease and complications. These guidelines recommend limiting use of indwelling catheters, insertion of catheters aseptically by trained personnel, hand hygiene before and after catheter manipulation, maintenance of a closed catheter system, avoiding routine irrigation unless the catheter is obstructed, avoiding routine catheter changes, keeping the collecting bag below the bladder, maintaining good hydration in residents and limiting antibiotics use.(12)

Leg bags for urine collection are used often in LTCFs and pose infection control dilemmas. Leg bags allow for improved ambulation of residents but can potentially increase the risk of UTI by compromising a closed drainage system. Reflux of urine from the bag to the bladder occurs more frequently than with a standard closed system. As a result, the use of leg bags is usually discouraged. It is recommended that a physician order be obtained before using a leg bag. Suggestions for care of leg bags include using aseptic technique when disconnecting and reconnecting, disinfecting connections, assuring that the leg bags are below the level of bladder, emptying bags every 4 hours, rinsing with diluted vinegar and drying between uses.(2)(12) A 1:3 dilution of white vinegar has been recommended for leg bag disinfection.(2)

Respiratory Tract Infections

Respiratory tract infections are either bacterial or viral in etiology. Because of the impaired immunity of older adults, viral upper respiratory infections that generally are mild in other populations may cause significant disease in the institutionalized elderly patient.(14) Examples of these viruses include influenza, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), parainfluenza, coronavirus, rhinoviruses, adenoviruses and the recently discovered human metapneumovirus.(15)Pneumonia and influenza illnesses are discussed in depth here.

Bacterial Pneumonia: Risk Factors

Pneumonia is the second most common cause of infection among LTCF residents with an incidence rate ranging from 0.3 to 2.5 episodes per 1000 resident care days. Pneumonia remains the leading cause of morbidity and mortality from infections in this setting. Older LTCF residents are predisposed to pneumonia due to decreased clearance of bacteria from the airways and altered throat flora, poor functional status, presence of feeding tubes, swallowing difficulties and aspiration, as well as inadequate oral care.16 Underlying diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and heart disease, further increase the risk of pneumonia in this population.(16)(17)

Signs and SymptomsThe clinical presentation of pneumonia in the LTCF residents is often atypical, although recent studies have shown that fever is present in 70%, new or increased cough in 61%, altered mental status in 38% and increased respiratory rate above 30 per minute in 23% of LTCF residents with pneumonia.(18) Acquiring a diagnostic sputum can be difficult, but obtaining a chest radiograph is now more feasible than in the past. In residents with suspected pneumonia, it is recommended that a pulse oximetry, chest radiograph, complete blood count with differential and blood urea nitrogen should be obtained.(19)

Etiologic Agents

Streptococcus pneumoniae appears to be the most common etiologic agent, accounting for about 13% of all cases, followed by Haemophilus influenzae (6.5%), Staphylococcus aureus (6.5%), Moraxella catarrhalis (4.5%) and aerobic gram-negative bacteria (13%).(17) Legionella pneumonia also is also a concern in the LTCF. Colonization with MRSA and resistant gram-negative bacteria further complicate diagnostic and management of pneumonia in LTCF residents.

Epidemiology

The mortality rate for LTCF-acquired pneumonia is significantly higher than for community-acquired pneumonia in the elderly population.(20) Pre-infection functional status, dementia, increased rate of respirations and pulse, and a change in mental status are considered to be poor prognostic factors. Several indices predictive of mortality have been developed and may be useful in managing residents with pneumonia. Decisions pertaining to treatment (oral versus intravenous antibiotics) as well as treatment site (transfer to acute care or manage in the facility) may be based on these prognostic indices.

Naughton et al., for example, derived a prediction model of 30-day mortality for LTCF pneumonia based on factors that can be readily identified by staff at the time of evaluation for pneumonia. The model included four predictors of 30-day mortality: respirator rate >30/minute (2 points), pulse >125/min (1 point), altered mental status (1 point) and a history of dementia (1 point). Mortality worsened with increased score (range from 0-5).18 Preventive Strategies

Pneumonia prevention efforts should focus on influenza and pneumococcal immunizations, handwashing after contact with respiratory secretions, wearing gloves for suctioning, elevating the head of the bed 30 to 45 degrees during tube feeding and for at least 1 hour after to decrease aspiration.(21) The evidence for the efficacy of pneumococcal vaccine in high-risk populations, including the elderly population, is debated. However, the vaccine is safe, relatively inexpensive and recommended for routine use in individuals over the age of 65 years.(22) Pneumococcal vaccine rates for LTCFs are now publicly reported at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid website http://www.medicare.gov/NHCompare/home.asp.

Influenza

Influenza is an acute respiratory disease signaled by the abrupt onset of fever, chills, myalgias and headache, along with sore throat and cough, although elderly LTCF residents may not have this typical presentation. The incubation period for influenza is approximately 1-2 days. It is a major threat to LTCF residents, who are among the high-risk groups deserving preventive measures.(23) Influenza is very contagious, and outbreaks in LTCFs are common and often severe. Clinical attack rates range from 25% to 70%, and case fatality rates average over 10%.(24)

Influenza vaccine in the elderly is approximately 40% effective at preventing hospitalization for pneumonia and approximately 50% effective at preventing hospital deaths from pneumonia.(2) Although concern has been expressed regarding the efficacy of the influenza vaccine for institutionalized elderly patients, most experts feel that it is effective and indicated for all residents and caregivers. Recent surveys have shown an increased rate of influenza vaccine use by LTCF residents, although significant variability exists.(25)(26) Influenza vaccine rates for a facility are now publicly reported at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid website: (http://www.medicare.gov/NHCompare/home.asp). LTCF staff immunization rates remain less impressive, with average immunization rates being 40%-50% at best.(26)

Diagnosis

While viral cultures from the nasopharynx remain the gold standard for diagnosis of influenza, several rapid diagnostic methods such as immunofluorescence or enzyme immunoassay have been developed. These tests detect both influenza A and B viral antigens from respiratory secretions. Amantadine-resistant influenza has been shown to cause NH outbreaks.(23)

Treatment

Zanamivir and oseltamivir are effective against both influenza A and B and have been approved for prophylaxis and treatment of influenza A and B. Zanamivir is given by oral inhalation with a potential of erratic absorption, particularly in a non-cooperative LTCF resident. Oseltamivir is administered orally and is excreted in the urine, requiring dose adjustments to prevent renal impairment.

Rapid identification of cases in order to promptly initiate treatment and isolate them to prevent transmission remains the key to controlling influenza outbreaks. Other measures recommended during an outbreak of influenza include restricting admissions or visitors, and cohorting residents with influenza. Long-term care facilities are encouraged to have non-punitive sick leave policy allowing the affected staff to stay home.

Skin and Soft-tissue Infections

Pressure ulcers

Pressure ulcers occur in up to 20% of residents in LTCFs and are associated with increased mortality.(27) Infected pressure ulcers often are deep soft-tissue infections and may have underlying osteomyelitis; secondary bacteremic infections have a 50% mortality rate. They require costly and aggressive medical and surgical therapy.

Risk Factors

Medical factors predisposing to pressure ulcers have been delineated and include immobility, pressure, friction, shear, moisture, incontinence, steroids, malnutrition and infection. Reduced nursing time can also increase the risk of developing pressure ulcers. Several of these factors may be partially preventable (such as malnutrition and fecal incontinence). Prevention of pressure ulcers involves developing a plan for turning, positioning, eliminating focal pressure, reducing shearing forces and keeping skin dry. Attention to nutrition, using disposable briefs, and identifying patients at a high risk using prediction tools can also prevent new pressure ulcers.

Management

Once infected, pressure ulcer management requires a multidisciplinary approach with involvement of nursing, geriatrics and infectious disease specialists, surgery and physical rehabilitation. The goals are to treat infection, promote wound healing and prevent future ulcers.

Many physical and chemical products are available for the purpose of skin protection, debridement and packing, although controlled studies are lacking in the area of pressure ulcer prevention and healing. A variety of products may be used to relieve or distribute pressure (such as special mattresses, kinetic beds or foam protectors) or to protect the skin (such as films for minimally draining stage II ulcers, hydrocolloids and foams for moderately draining wounds, alginates for heavily draining wounds). Negative pressure wound therapy, using gentle suction to provide optimal moist environment, is increasingly being employed in the treatment of complex pressure ulcers.

Nursing measures such as regular turning are essential as well. A pressure-ulcer flow sheet helps detect and monitor pressure ulcers by recording information such as ulcer location, depth, size, stage and signs of inflammation, as well as the timing of care measures. Infection control measures include using diligent hand hygiene measures and glove usage.(28)(29)(30)

Because all pressure ulcers, like the skin, are colonized with bacteria, antibiotic therapy is not appropriate for a positive surface-swab culture without signs and symptoms of infection. True infection of a pressure ulcer (cellulitis, osteomyelitis, sepsis) is a serious condition, generally requiring broad-spectrum parenteral antibiotics and surgical debridement in an acute-care facility.

Scabies

Scabies is a contagious skin infection caused by a mite. Lesions usually are very pruritic, burrow-like with erythema and excoriations, and occur most commonly in the interdigital spaces of the fingers, palms and wrists, axillae, waist, buttocks and the perineal area. However, these typical findings may be absent in debilitated LTCF residents, leading to large, prolonged outbreaks.(31)(32)(33)

Diagnosis

Diagnosis in an individual with a rash requires a high index of suspicion in order to recognize the need for diagnostic skin scrapings. Scabies should always be considered with other causes of rash such as drug rash, contact dermatitis, urticaria, herpetic infections (zoster and simplex) and eczema. The presence of a proven case should prompt a thorough search for secondary causes.

Treatment

A single treatment with permethrin or lindane usually is effective, but repeated therapy or treatment of all LTCF residents, personnel and families is occasionally necessary. Ivermectin, an oral antihelminthic agent, is an effective, safe and inexpensive option for the treatment of scabies. Therapy of rashes without confirming the diagnosis of scabies unnecessarily exposes residents to the toxic effects of the topical agents. Because scabies can be transmitted via linen and clothing, the residential environment should be cleaned thoroughly. This includes cleaning inanimate surfaces, hot-cycle washing of washable items (clothing, sheets, towels, etc.) and vacuuming the carpet.

Other infections

Gastroenteritis is common and disabling to older LTCF residents. Infectious gastroenteritis can also spread rapidly within a facility leading to substantial functional decline and hospital transfers. Infectious gastroenteritis can be viral (caused by rotavirus and enteroviruses including Norwalk virus), bacterial (caused by Clostridium difficile, Bacillus cereus, Escherichia coli, Camplylobacter, Clostridium perfringens and Salmonella) and parasitic (such as Giardia lambia). Foodborne disease outbreaks also are very common in this setting, most often caused by Salmonella or S. aureus. E. coli O157:H7 and Giardia also may cause foodborne outbreaks, underscoring the importance of proper food preparation and storage.

Epidemiology

Bacteremia is rarely detected in LTCFs, although its prevalence may increase with increasing availability of diagnostics. Bacteremias are usually secondary to infection at other sites such as UTIs, pneumonia, skin and soft tissue infections. The most common source of secondary bacteremia is the urinary tract, with E. coli the etiologic agent in over 50% of cases.(34)

With increasing severity of cases seen in the subacute care setting, the use of peripherally inserted central catheters is expected to rise leading to increased risk of local and systemic catheter-related infections. Prevention of peripheral intravenous (IV) catheter-related infections should include aseptic insertion of the IC cannula, daily inspection of the IV for complications such as phlebitis, and quality control of IV fluids and administration sets.

Summary

Infections in LTCF residents are common, morbid and often difficult to diagnose and treat. Increased vigilance to their subtle presentation, optimizing antibiotic therapy with a goal to reduce inappropriate antibiotic usage and supportive therapy are crucial to early recovery from infections and related functional decline.