Course Authors

Stephen Pandol, M.D., and Hartley Cohen, M.D.

Dr. Pandol is Professor of Medicine, UCLA School of Medicine and Staff Physician, Department of Medicine, VA Greater Los Angeles Health Care System and University of California, Los Angeles. Dr. Cohen is Clinical Professor of Medicine, UCLA School of Medicine and Director of Endoscopy, Department of Medicine, VA Greater Los Angeles Health Care System and University of California, Los Angeles.

Within the past 12 months, Drs. Pandol and Cohen report no commercial conflicts of interest.

This activity is made possible by an unrestricted educational grant from ![]() Solvay.

Solvay.

Estimated course time: 1 hour(s).

Albert Einstein College of Medicine – Montefiore Medical Center designates this enduring material activity for a maximum of 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

In support of improving patient care, this activity has been planned and implemented by Albert Einstein College of Medicine-Montefiore Medical Center and InterMDnet. Albert Einstein College of Medicine – Montefiore Medical Center is jointly accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME), the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE), and the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC), to provide continuing education for the healthcare team.

Upon completion of this Cyberounds®, you should be able to:

Discuss the risk factors for chronic pancreatitis

Identify patients who may have chronic pancreatitis

Describe the approaches and limitation to the diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis

Treat patients with chronic pancreatitis including management of pain, exocrine and endocrine insufficiency

Discuss the complications of chronic pancreatitis including development of pseudocysts, ascites and pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

Histologically, chronic pancreatitis is defined as irreversible damage to the pancreas with the development of chronic inflammation, fibrosis and destruction of exocrine (acinar cells and ducts) and endocrine (islets of Langerhans) tissue. In advanced disease, this damage is associated with calcifications and ductal abnormalities.

Because it is rare to obtain tissue from patients for histologic examination, there have been several clinically applicable strategies using pancreatic function and imaging tests to identify patients who likely have chronic pancreatitis. As will be detailed below, there are limitations to these proxy tests, especially because they lack the sensitivity to identify patients in early stages of the disease. Awareness of these difficulties in diagnosis is necessary in approaching patients with the possibility of chronic pancreatitis.

Epidemiology and Prevalence

By far the most common etiology of chronic pancreatitis is alcohol abuse, estimated to cause 60-90% of the cases (Figure 1). Approximately 20% of the cases are classified as idiopathic. About 10% of the cases are caused by hereditary pancreatitis (a disorder resulting from mutations in trypsinogen), cystic fibrosis, hyperparathyroidism, hypertriglyceridemia, obstruction of the pancreatic duct, pancreatic divisum (a congenital abnormality of fusion of the ducts of the embryological ventral and dorsal pancreas), trauma, tropical pancreatitis and autoimmune pancreatitis. The latter is a rare type of chronic pancreatitis but has been increasingly recognized as sometimes mimicking pancreatic cancer, and unlike other types of chronic pancreatitis, histologic and clinical manifestations including mass lesions, biliary obstruction and pancreatic duct strictures resolve with corticosteroid treatment.

Figure 1. Etiologies.

The incidence and prevalence of chronic pancreatitis are difficult to ascertain with precision, in part because of the variable nature of clinical manifestations of the disease and the difficulties in diagnosis alluded to above. Furthermore, with respect to alcohol-induced pancreatitis, there is a continuum of disease manifestations from acute to chronic pancreatitis such that the distinction between acute and chronic disease without histologic material is somewhat difficult. Finally, findings consistent with chronic pancreatitis have been demonstrated in up to 75% of autopsies done on alcohol abusers suggesting that the disorder is significantly under diagnosed. With these considerations in mind, reports of prevalence show rates varying from 4-33 per 100,000.(1),(2),(3)

Alcoholic pancreatitis occurs predominantly in men. The risk of developing alcohol-induced chronic pancreatitis is related to the amount and duration of drinking. A minimum of 6-12 years of drinking 80 g or more of alcohol are generally considered required for development of the disease. However, only 10-15% of heavy drinkers develop chronic pancreatitis, indicating that, in addition to alcohol abuse, other environmental or genetic factors are involved in the development of chronic pancreatitis.

Epidemiological studies supporting other factors in the etiology of the disorder show that African American patients are 2-3 times more likely than white patients to be hospitalized for chronic pancreatitis than alcoholic cirrhosis; and that both Native Americans and Alaskan Natives have the highest rates of alcohol-induced liver cirrhosis of any ethnic/racial group in the US but have rates of chronic pancreatitis similar to those of whites.(4),(5),(6)

Both smoking and dietary factors may contribute to the risk of alcoholic chronic pancreatitis. Recent studies(7),(8) demonstrate that cigarette smoking is an independent risk factor for alcohol-associated pancreatitis and that smoking accelerates that progression of the disease. Diets high in protein and fat appear to exacerbate the course of chronic pancreatitis, whereas saturated fats and vitamin E may act to decrease alcohol's effect.

Pathobiology

The pathobiologic processes of chronic pancreatitis include acute and chronic inflammation and fibrosis with the loss of parenchymal cells of the exocrine and endocrine pancreas (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Proposed Necrosis-Fibrosis Sequence.

These processes lead to irreversible and debilitating exocrine and endocrine insufficiency, and a severe chronic pain syndrome. Alcohol abuse may cause episodes of recurrent acute pancreatitis with increasing amounts of fibrosis, chronic inflammation and parenchymal cell loss with each successive episode. On the other hand, these processes may proceed silently over years with progressive fibrosis and loss of function without symptoms of acute pancreatitis. Of particular note, the processes of chronic pancreatitis continue even after complete cessation of alcohol intake, which indicates that the processes are self-sustaining once a certain stage of the disease is reached. Adding to the morbidity and mortality of this disorder is the fact that patients with chronic pancreatitis are at significant increased risk for pancreatic cancer.

A leading hypothesis called "the necrosis-fibrosis sequence" provides a basis for understanding the disorder, based on pancreatic tissue examination during alcoholic acute and chronic pancreatitis.(9),(10),(11) In particular, early after the onset of chronic pancreatitis symptoms, there is evidence of postnecrotic changes in the pancreas such as pseudocyts; and morphology from surgical specimens shows predominant pancreatic lesions of focal necrosis and mild fibrosis. In contrast, specimens several years after the onset of symptoms obtained at autopsy show severe perilobular and intralobular fibrosis and calcification with no necrosis.

What are the factors that initiate and sustain the necrosis-fibrosis sequence of chronic pancreatitis? Although the mechanisms are not identified in humans, there is emerging evidence that alcohol sensitizes the pancreas to the pathobiological responses that mediate the disease. For example, alcohol promotes both the acute inflammatory response and sustains the chronic inflammatory response in the pancreas after a stressful injury. Further, alcohol has been demonstrated to enhance necrosis of acinar cells through effects on death pathways; and promote fibrogenesis by enhancing the proliferation and extracellular matrix production of myofibroblasts in the pancreas.

Common Clinical Manifestations of Chronic Pancreatitis Pain

Abdominal pain and exocrine and endocrine pancreatic insufficiency account for most of the clinical manifestations of chronic pancreatitis. Pain is the most common clinical manifestation and the hallmark of chronic pancreatitis, occurring in 80% of the diagnosed cases. Sometimes simulating the pain of pancreatic cancer, chronic pancreatitis pain may be severe, unrelenting, epigastric, radiating to the back, exacerbated by food ingestion and associated with weight loss, although appetite may be well preserved (in contrast to anorexia in patients with pancreatic carcinoma). As in pancreatic cancer, the fetal position may provide some relief.

There are many different patterns of pain: occasional or intermittent; frequent or recurrent; mild, moderate or severe; and at times associated with nausea and vomiting. At times, pain seems to correlate with "flares" - what appears to be a clinical attack of acute pancreatitis superimposed on a background of a previously established diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis. In the latter setting, amylase and lipase often are normal or only mildly elevated. Intermittent attacks of pain (i.e., the flares) have been labeled type A pain pattern, while prolonged periods of pain or pain occurring for at least a few days every week have been termed Type B pattern.

Table 1. Clinical Manifestations and Complications of Chronic Pancreatitis.

|

Clinical Manifestations

Complications

|

Especially among alcoholics, it may be very difficult to assess the significance of complaints of pain, as personality disorders and potential narcotic addiction cloud the presentation. A commonly held view is that persistent alcohol consumption exacerbates pain but this is difficult to substantiate. Studies(12) suggest that alcohol abstinence leads to some improvement in pain in about half of such patients as compared to pain relief occurring in about a quarter of patients despite continued alcohol misuse.

Generally, the pain of chronic pancreatitis spontaneously wanes over the course of a decade. Some believe that with advanced disease, with loss of functioning parenchymal tissue leading to exocrine and endocrine deficiency (sometimes called burnout), the pain subsides. However, the evidence to support this belief is conflicting.(12)

Complications of chronic pancreatitis can confound the assessment of pain. For example, pseudocysts, biliary obstruction or the occurrence of pancreatic adenocarcinoma in the setting of chronic pancreatitis may cause or exacerbate pain. Additionally, other diseases causing epigastric pain (e.g., peptic ulcer disease) may coexist.

Exocrine Insufficiency

Exocrine insufficiency is defined as steatorrhea. The exocrine pancreas has sufficient reserve so that steatorrhea does not occur in chronic pancreatitis until 90% of the exocrine pancreas is lost. Patients with exocrine insufficiency may also maldigest protein and carbohydrate, although maldigestion of fat is the most significant.

Patients with exocrine pancreatic insufficiency often describe bulky, foul smelling stools and even oil droplets in the toilet bowel. These patients often also have diarrhea and weight loss. However, they usually do not have watery diarrhea, excessive gas and abdominal cramps as occurs with other forms of malabsorption. Even with significant loss of fat in the stool, most patients with pancreatic exocrine insufficiency only pass three to four stools per day.

Of note, because fat soluble vitamins accumulate in the oil phase of the bowel contents, patients with exocrine insufficiency can have malabsorption of such vitamins and become deficient. For example, recent studies show increased rates for osteopenia and osteoporosis in these patients.(13)

Endocrine Insufficiency

Although islets are relatively resistant to destruction during chronic pancreatitis, they do fail in long-standing disease. In chronic pancreatitis both the insulin-secreting β cells and the glucagon-secreting α cells fail, so that the patient does not have the ability to respond to hypoglycemia with the glycemic effect of glucagon. These patients are often described as "brittle diabetics" and require significant caution in treatment because of the increased risk of hypoglycemia.

Complications of Chronic Pancreatitis

Pseudocysts

Pseudocysts occur in 20-40% of patients with chronic pancreatitis. The pseudocysts can be asymptomatic or discovered as a result of imaging studies performed to evaluate one or another symptom including early satiety, nausea, weight loss and, probably most commonly, changes in abdominal pain patterns. Why some pseudocysts cause abdominal pain while others are asymptomatic is not known. An acute exacerbation of pain (Type A pain) may reflect a flare of pancreatitis and or herald the presence of a pseudocyst, which may not necessarily be "mature." The mechanism of pseudocyst development probably involves a small ductal disruption that leads to a confined and slow fluid accumulation eventually recognized as a pseudocyst.

Impingement of large (>5 cm) pseudocysts on the stomach or duodenum probably explains early satiety, nausea, vomiting and weight loss in some patients. Infrequently, jaundice may occur as a result of bile duct compression from a pseudocyst located in the head of the pancreas. Manifestations of infection (i.e., pain, fever and leukocytosis) may lead to imaging studies and subsequent diagnosis of infected pseudocyst or even an abscess. Rupture of a pseudocyst intra-abdominally presents as an abdominal catastrophe secondary to chemical peritonitis and emergency surgery is indicated. Pseudocysts may form in remote locations from the pancreas and produce space-occupying symptoms leading to their diagnosis. Pseudocysts very infrequently leak and cause pancreatic ascites and/or pleural effusions.

Pancreatic Fistula and Its Major Consequences - Pancreatic Ascites and Pancreatic Pleural Effusions

Pancreatic fistulas result from pancreatic duct disruptions. Fistulas either communicate with the skin ("external fistulas") or lead to pancreatic juice accumulations within the body ("internal fistulas"). External fistulas are always iatrogenic unless associated with trauma. They occur as a result of percutaneous interventions or surgery. Internal fistulas presumably occur as a result of inflammation and relative high pancreatic ductal pressure either from strictures or stones occluding the duct downstream from the site of duct disruption. Presumably, sphincter of Oddi pressure or hypertension also contribute to duct disruption and maintenance of fistula patency. It is the consequences of duct disruption that are clinically relevant. For example, in the setting of chronic pancreatitis, consequences include pseudocysts (see above), pancreatic ascites and pleural effusions.

Pancreatic ascites mostly presents indolently. Patients present with a history of increasing abdominal girth, minor abdominal discomfort and weight loss despite fluid retention. Occasionally, patients may have dyspnea, especially if there is an accompanying large (usually left-sided) pleural effusion. It is curious that a clinical acute peritonitis, as occurs with sudden rupture of a pseudocyst, is not present. Chronic alcoholic pancreatitis is the primary underlying disease and, overall, ascites occurs in ~3% of all patients with chronic pancreatitis. About half of patients with pancreatic ascites have a history of pancreatitis. However, an episode of clinical acute pancreatitis (Type A pain pattern) immediately preceding presentation with ascites is unusual. In marked contrast to the ascites of large volume seen in chronic pancreatitis, a few patients with acute severe pancreatitis may develop a small volume of pancreatic fluid in the abdominal cavity. Trauma is a rare cause of pancreatic ascites.

Pancreatic ascites in about half the cases results from a communication or fistula directly from the pancreatic ductal system, while in the other 50% of cases it occurs indirectly from the ductal system via a leaking pseudocyst. Duct rupture or pseudocyst leak into the peritoneal space result in pancreatic ascites, while duct leakage into the retroperitoneal space may lead to tracking through the aortic or esophageal hiatus into the chest. Pancreatic chest communications rarely include pancreaticobronchial or pancreaticopericardial fistulas. The major chest manifestation of a pancreatic fistula is pleural effusion.

Bile Duct Strictures

The clinical manifestations in patients with bile duct strictures are variable and range from no symptoms to abdominal pain indistinguishable from that of the associated underlying chronic pancreatitis. Type A pain or an exacerbation of Type B pattern may reflect an "acute on chronic pancreatitis flare" and may be associated with jaundice secondary to increased edema of the head of the pancreas constricting (or further constricting an already narrowed) distal common bile duct (the intrapancreatic portion of the bile duct). Progressive chronic pancreatitis in the absence of a "flare" also may result in overt jaundice because of bile duct stricture. Cholangitis is a much less common presentation unless coexisting common bile duct (CBD) stones are present.

Splenic Vein Thrombosis

The splenic vein courses along the posterior aspect of the pancreas and as a result of inflammation of the pancreas splenic vein thrombosis may occur. This leads to gastric varices [sinistral (left side) portal hypertension]. Both occult bleeding and major bleeding can occur from these gastric varices. Portal vein obstruction also may occur with similar sequelae.

Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma

Pancreatic cancer occurs with increased frequency among chronic pancreatitis patients compared to the general population. The cumulative incidence is ~2% per decade. Overall, however, these patients account for at most 5% of all cases of pancreatic cancer. The manifestations of pancreatic cancer may be indistinguishable from those of the underlying chronic pancreatitis. Worsening of pain, onset of jaundice, weight loss, development of migratory thrombophlebitis or onset of depression may prompt consideration of pancreatic cancer.

Diagnostic Testing for Chronic Pancreatitis

Most patients with chronic pancreatitis will present to the clinician with abdominal pain. Some of these patients may additionally have steatorrhea and a few may have steatorrhea alone. A history of alcohol abuse, smoking, steatorrhea and previous episodes of acute pancreatitis will bring up the consideration of chronic pancreatitis. However, the clinician must be aware that even if the patient is found to have evidence of chronic pancreatitis, the pain can be secondary to other causes. In addition, the pain may be a manifestation of "drug seeking behavior"/addiction in patients treated with narcotics. A complication of chronic pancreatitis such as a pseudocyst may present with pain as well.

The gold standard tests for chronic pancreatitis are pancreatic function tests described later in this section. With the exception of the stool fat measurement, these tests are rarely used. Loss of dietary lipid in the stool (steatorrhea) occurs in advanced chronic pancreatitis. Of note, steatorrhea does not occur until there is loss of approximately 90% or greater of the pancreatic exocrine tissue. Initially, this measurement can be done simply by staining the stool with an oil soluble dye and observing the specimen under the microscope for oil droplets. This test is formalized in most clinical laboratories. Furthermore, a quantitative measure of stool fat should be obtained during a time that the patient is taking in a defined amount of dietary fat (commonly 100 g per day).

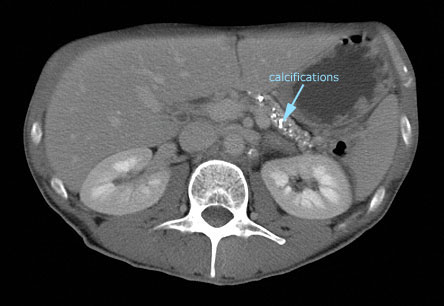

For the diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis in patients without steatorrhea, we favor imaging tests to determine if there is evidence of chronic pancreatitis with or without one of the complications (Table 2). A CT scan of the abdomen is an appropriate initial imaging test to evaluate for chronic pancreatitis. Findings of an atrophic gland, calcifications in the gland and/or dilation of the main pancreatic duct provide evidence for chronic pancreatitis. Of note, there are no abnormal findings in early chronic pancreatitis. The CT findings will also identify complications such as pseudocyst, biliary dilation, pancreatic adenocarcinoma or concomitant findings suggestive of an "acute on chronic pancreatitis flare." Depending on the CT findings, additional imaging with magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) or MR may be warranted.

Table 2. Imaging Tests for Chronic Pancreatitis.

| Test | Mild Disease | Severe Disease | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| CT | Poor | Very good | Detects calcification, duct dilation |

| MRCP | Poor | Very good | Defines ductal anatomy |

| EUS | Good | Very good | Less invasive than ERCP |

| ERCP | Good | Very good | Risk of pancreatitis |

Figure 3. CT Image of the Pancreas in a Patient with Chronic Pancreatitis.

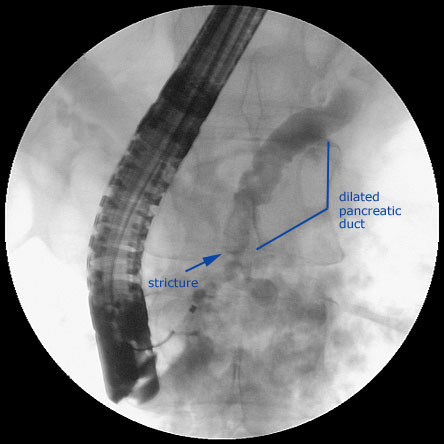

Figure 4. ERCP in a Patient with Chronic Pancreatitis.

Much more difficult is the assessment of abdominal pain in early disease when CT and MR imaging are normal. As the pain of chronic pancreatitis is very variable and its characteristics may mimic pancreatic carcinoma, peptic ulcer disease, abdominal ischemia and functional abdominal pain et al., it is sometimes necessary to pursue extensive diagnostic evaluation. A history of alcohol consumption may help focus on the possibility of chronic pancreatitis. However, the absence of a history of alcohol use is not helpful, as idiopathic chronic pancreatitis may be the culprit. Of note, genetic testing for a predisposition to pancreatitis may be helpful. Genetic testing for cystic fibrosis and hereditary pancreatitis can be considered.

If the abdominal CT and MRI studies are unrewarding and there is a sufficient suspicion and justification for pursuing the diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis (i.e., consistent pattern, frequency, severity of pain), it may be appropriate to consider endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) of the pancreas. EUS has minimal morbidity very similar to that of routine upper endoscopy. The EUS criteria for diagnosing chronic pancreatitis are in flux but there is agreement among experts that EUS can provide information about the pancreatic duct and parenchyma to make a diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis especially if 5 or more criteria are present. Endoscopic retrograde pancreatography (ERCP) has comparable accuracy to EUS for diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis. However, EUS is preferred over ERCP, as the latter is associated with life-threatening complications at an unacceptable rate. Thus, we do not recommend the use of ERCP to make the diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis.

Pancreatic function testing is not routinely available but has been labeled as the gold standard for diagnosing chronic pancreatitis (Table 3). Pancreatic secretions are sampled from the duodenum after either a standard meal or with secretin or cholecystokinin stimulation. The secretion is analyzed for enzyme and bicarbonate concentrations.

Table 3. Pancreatic Function Tests.

| Test | Mild Disease | Severe Disease | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Secretion | |||

| Endoscopic collection | Uncertain | Good | Invasive; optimal collection time unclear |

| Dreiling Tube | Very good | Very good | Uncomfortable, expensive, difficult to obtain |

| Stool proteases | Poor | Good | Moderate cost |

| Absorption | |||

| 72-hr stool fat | Poor | Very good | Cumbersome, non-specific |

| Stool fat stain | Poor | Good | Inexpensive |

Historically, a special tube made to separately collect gastric and pancreatic secretions (Dreiling tube method) was used to aspirate duodenal contents. More recently, upper endoscopic techniques for collection have been described.(14) In chronic pancreatitis, the concentrations of both enzymes and bicarbonate are decreased in the pancreatic juice. Because of the time needed for the collection and the fact that the measurements are not routinely done in clinical laboratories, these tests will not likely gain wide acceptance. Tubeless tests have been developed that determine the amount of enzymes secreted by the pancreas both by measuring pancreatic enzymes (proteases) in the stool and by using substrates that are cleaved by the digestive enzymes and result in absorption of a product of the enzyme action that can be measured in the serum or urine. Unfortunately, all of the tubeless tests do not have sufficient sensitivity to measure lesser decreases in pancreatic secretions that occur in chronic pancreatitis patients without steatorrhea.

Diagnosis of Complications of Chronic Pancreatitis Pseudocysts

We prefer CT scanning initially. Pseudocysts are usually single, unilocular, located anywhere in the pancreas and homogenous. So-called "retention cysts," however, are located in the head and may be multiple. The differential diagnosis of cystic lesions in and around the pancreas also includes cystic neoplasms. There is no reason to believe that patients with chronic pancreatitis are immune from cystic neoplasms or other types of cysts but, in this clinical setting, hearing hooves should not make one think of zebras, unless the imaging is atypical. If infection is suspected clinically, percutaneous sampling of the pseudocyst, followed by bacterial culture, should be performed. A percutaneous drain should be placed at the time of sampling if the aspirated fluid appears to be infected. A change in size or density of a pseudocyst on CT scan or evidence of blood loss should suggest bleeding into the pseudocyst from a ruptured pseudoaneurysm.

Pancreatic Fistula and Its Major Consequences -- Pancreatic Ascites and Pancreatic Pleural Effusions

Because of its generally indolent course and because a history of alcohol abuse is usually present, the initial clinical suspicion for the cause of ascites is likely to be alcoholic liver disease/cirrhosis/portal hypertension. If it is known that the patient has underlying chronic pancreatitis, it is much easier to think of the diagnosis of pancreatic ascites. Imaging studies may be indicative of chronic pancreatitis by revealing pancreatic calcifications and/or pseudocysts. Over half of the patients with pancreatic ascites also have pseudocysts. In patients with pancreatic ascites, the serum amylase usually is mildly elevated (possibly as a result of amylase absorption from the ascites fluid into the circulation). Aspiration and analysis of a sample of ascites fluid typically reveal an albumin >3g/100 ml. Thus, almost always, the serum-ascites albumin gradient is <1.1 and, if pancreatic ascites has not been considered previously, this should prompt its inclusion in the differential diagnosis. The sine qua non for diagnosis is an ascites-serum amylase gradient >1 or ascites amylase >1000 units. The ascites white blood cell count is often in the thousands and possibly reflects a sub-clinical chemical peritonitis. Infection must be excluded.

Pancreatic pleural effusions will have similarly markedly increased levels of amylase.

ERCP is needed to demonstrate that fistula are causing the ascites or pleural effusion. It is not performed simply to show the fistula but is used to define ductal anatomy in combination with performing endoscopic therapy, as described below.

Bile Duct Strictures

Overt jaundice or bilirubin elevation and even isolated alkaline phosphatase elevation may occur. The diagnosis is made on the basis of imaging studies (ERCP or MRCP) that show stricture of the distal CBD. In this situation, one must also consider the diagnosis of obstruction of the common bile duct caused by a pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

Splenic Vein Thrombosis

With splenic vein thrombosis, endoscopy may reveal gastric varices in the absence of esophageal varices. Sometimes, the gastric varices are difficult to identify and differentiate from gastric folds and EUS or extracorporeal imaging methods (including Doppler ultrasonography) may be needed. Splenomegaly is common. Thus, the diagnosis of splenic vein thrombosis should be suspected in patients with chronic pancreatitis, splenomegaly and upper gastrointestinal bleeding secondary to gastric varices.

Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma

The diagnosis of pancreatic adenocarcinoma may be made serendipitously at the time of surgery for pain of chronic pancreatitis. Imaging studies may reveal focal enlargement of the head of the pancreas, which should prompt EUS with fine needle aspiration. PET scanning may be helpful but false positives occur in the presence of pancreatic necrosis. Generally. the diagnosis is not made until the disease is beyond cure.

Management of Symptoms and Complications of Chronic Pancreatitis

Pain

Theoretically, the treatment of pain in chronic pancreatitis would be "easy" or at least potentially rational if only we understood the mechanisms of pain generation and had the means to modulate these mechanisms. Unfortunately, the mechanisms are not known. Multiple mechanisms have been postulated including ductal hypertension, parenchymal hypertension (akin to "compartment syndrome" and induction of ischemia), neural sheath inflammation and disruption, and inflammatory mediators. Perhaps, different postulates/mechanisms are applicable to different patients. For example, there may be differences in mechanism as a function of etiology - alcoholic, genetic or idiopathic. There also may be differences as a function of morphology -- minimal changes versus end-stage with dilated large ducts and calcifications.

Table 4. Pain Management in Chronic Pancreatitis.

| Treatment | Effectiveness | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| No alcohol | Low to moderate | Pain may continue despite cessation of alochol abuse |

| Analgesics | Moderate | Addiction to narcotics develops |

| Pancreatic enzymes | Low | Limited to idiopathic early disease in women |

| Neurolytic therapy | Moderate | Usually short-term benefit |

| Pseudocyst drainage | High | Symptom relief when the pseudocyst is etiology of pain |

| Surgical duct drainage | Moderate | Used in patients with dilate ductal system |

| Store removal | Low | Controversial |

Mild infrequent pain is treated with non-narcotic analgesics on an as needed basis. Alcohol abstinence is encouraged, although the relationship of alcohol to pain is not established. However, alcohol generally promotes progression of disease. The approach to treatment is directed at symptoms. It is empiric and may include antidepressants. The intention is to relieve symptoms but to avoid potent narcotics, as the latter guarantee drug addiction.

Based on very limited data, it also is rational to attempt to treat pain based on patient characteristics, as suggested above. Women with idiopathic chronic pancreatitis and minimal morphological pancreatic changes may respond to the administration of oral pancreatic enzymes. The underlying concept is to place the pancreas at rest.

The postulated mechanisms, whereby pancreatic enzymes may be effective, are as follows. Cholecystokinin (CCK) is the major stimulator of pancreatic enzyme secretion. CCK is released from the small intestine with a meal but is also regulated by the amount of digestive enzymes in the lumen of the GI tract. The effect of digestive enzymes results from the degradation of intraluminal CCK-releasing peptides. Thus, with increases in the amount of pancreatic enzymes in the lumen, there is greater degradation of the CCK-releasing peptides and this leads to a diminution of CCK release into the blood and decreased pancreatic stimulation. Even if such treatment proves ineffective, there is little downside. Because the effect likely requires delivery of the enzymes into the duodenum, for this situation non-enteric coated enzyme preparations (pancrealipase) should be used, together with acid-suppressive treatment to prevent degradation of enzymes by gastric acid. Studies that show benefit also use high doses of pancreatic enzymes (equivalent to 30,000 units of lipase with meals and at night).

For patients with more or less constant debilitating pain (so-called B type pain) who do not respond to medical treatment as above and for whom potent narcotics are considered (if not already started), nerve blocks, endoscopic interventions and surgery are considerations.

Unfortunately, nerve blocks of the celiac ganglion by either CT guidance or by EUS have been disappointing. However, a few patients do respond, at least transiently. The EUS technique may be the one of choice, as it provides the most direct access, may have a lower rate of complication and may be minimally more effective compared to CT guidance. Given the relative simplicity of EUS-guided celiac ganglion injection and acceptable complications (primarily transient diarrhea and hypotension), it seems reasonable to try this modality before embarking on more complex surgical alternatives including denervation procedures such as surgical resection of the splanchnic nerve and the celiac ganglion. Unfortunately, denervation procedures usually have been combined with other surgical maneuvers which obscure the potential benefit of the denervation procedure itself.

Traditionally, it has been assumed that intraductal hypertension, secondary to strictures and/or obstructive pancreatic duct stones, causes pain. Therefore, surgical drainage procedures have been performed, especially on patients with markedly dilated pancreatic ducts, to relieve the presumed hypertension. The surgery involves opening the main pancreatic duct along its long axis, combined with anastamosis to a portion of small bowel, for drainage of its secretions. The surgical results have been interpreted as successfully relieving pain in the majority of patients but rigorous studies have not been performed.

Based on the belief that drainage procedures relieve pain, endoscopic procedures to accomplish "drainage" have been performed. Thus, pancreatic sphincterotomy, pancreatic duct stenting, pancreatic duct stone extraction with and without extracorporeal lithotripsy and stricture dilation have been performed. In mainly retrospective case analyses, it has been claimed that more than half the patients treated by these endoscopic methods (endotherapy) have amelioration of pain. The data is difficult to interpret but endotherapy, in general, may help postpone surgery and obviate the need for surgery in individual patients. Unfortunately, as with the selection of patients for surgery, there are no agreed upon criteria to select patients who are likely to have long-lasting pain relief by endotherapy. However, given the relatively lower morbidity of endotherapy, as compared to surgery, endotherapy seems to be a reasonable option in patients with appropriate ductal anatomy and debilitating pain.

In addition to surgical drainage procedures in patients with dilated ducts, pancreatic resections (for presumed parenchymal hypertension and coincidental removal of inflamed neural sheaths), especially of a portion of the head of the pancreas (conceptually considered the pacemaker area for pancreatic pain and usually the site of focal enlargement for unclear reasons) have been performed with the claim that results of such surgery are superior to simple drainage procedures. Sometimes, only resection surgery is possible as the ducts are not dilated and, occasionally, total pancreatectomies have been performed. Total pancreatectomy results in brittle diabetes. Thus, at the time of pancreatectomy, autologous islet cell transplantations have been performed with some success at complete insulin independence.

A randomized trial of patients with pain and pancreatic duct obstruction has evaluated endotherapy compared to surgery, the latter mostly consisting of limited pancreatic resections.(15) Pain relief was successful in both groups to a similar degree at one year. At the 5-year follow-up, pain relief was superior in the surgical group. However, complete absence of pain was present in only 34% of the surgical group, which leads us to believe that neither endotherapy nor surgery are reliably effective (perhaps because of the difficulty of selecting the appropriate patient and matching the patient to the "correct" surgical procedure) and that surgery should be reserved for a small proportion of chronic pancreatitics with Type B pain who fail other modalities. Indeed, in one center, the proportion of patients with chronic pancreatitis undergoing surgery for pain that is unrelated to a complication of chronic pancreatitis (e.g., pseudocysts, bile duct obstruction) is less than 10% of all patients with alcoholic chronic pancreatitis.(9)

Other treatments, based on the concept of resting, subduing or inhibiting the pancreas, have been tried. Octreotide therapy has been found to be ineffective.(16) Prolonged TPN has been used for a few patients with presumptive (i.e., normal imaging studies) idiopathic chronic pancreatitis in whom pain is especially exacerbated by eating. Pancreatitis is suspected because of the clinical presentation in association with usually mild, sometimes fluctuating elevations of amylase and lipase. These patients may have "smoldering pancreatitis" and typically it is unclear if there is an underlying chronic pancreatitis. Some of these patients have clear precipitants of acute pancreatitis (e.g., gallstones which are not thought to induce chronic pancreatitis) but in other patients the inciting event is occult. The natural history or the pathophysiologic mechanisms that underly this entity are not known and management is empiric. Fortunately, this is a tiny subset of patients. Anecdotally, pancreatic duct stenting has helped in a few patients. There may be some improvement in pain with intensive antioxidant treatment as shown in a recent study.(20)

Exocrine and Endocrine Insufficiency

Treatment of maldigestion and steatorrhea generally requires administration of 30,000 units of lipase to the intestine with each meal. This can be accomplished with both enteric-coated and non-enteric-coated preparations. The best approach is to have the patient divide the dose into three portions to be taken at the beginning, middle and end of a meal. If non-enteric-coated preparations are used, the patient should also receive sufficient proton pump inhibitor therapy to prevent enzyme inactivation as the preparation passes through the stomach. The effectiveness of the treatment is generally gauged by the clinical response. In other words, how effective is the treatment in decreasing stool frequency and visible steatorrhea, while increasing weight. These parameters should be monitored in each case. If the patient does not respond, one should consider increasing the dose of pancreatic enzymes and/or proton pump inhibitor. Also, particular patients may benefit from smaller and more frequent meals. Finally, if these measures fail, one can consider replacing dietary fat with medium-chain triglycerides which do not require pancreatic enzymes for absorption.

Because of the potential for fat soluble vitamin deficiency, these patients should receive supplements of vitamin D and calcium.

The treatment of diabetes mellitus in patients with chronic pancreatitis requires special consideration because these patients are more prone to hypoglycemia, as discussed earlier. Further, if the patient is using narcotics for pain relief and/or continuing alcohol abuse, further precautions are necessary. The treatment should be individualized and it may not be prudent to "tightly" control blood glucose levels in many of these patients. Of note, patients with endocrine insufficiency of chronic pancreatitis will respond to oral hypoglycemic agents. However, insulin therapy is required for many of these patients.

Pseudocysts

In general, on discovery, pseudocysts in chronic pancreatitis are considered mature and may be treated immediately if symptomatic. However, if the pseudocyst is an"incidental finding" on imaging studies, it may be ignored on the short-term irrespective of size. Over the long-term, the concern is that a major complication may occur (pseudoaneurysm, perforation, abscess formation). Unfortunately, however, the natural history of pseudocysts is poorly defined. Nonetheless, asymptomatic pseudocysts may be observed safely with repeat imaging every 6 months for one year. If the patient becomes symptomatic, or the pseudocyst increases in size during follow up, intervention is indicated. Whether imaging studies need to be repeated in the asymptomatic patient indefinitely is unclear. Our bias is not to do so but to follow the patient clinically. However, as only a mere ~10% of patients with alcoholic chronic pancreatitis are pain-free over many years,(9) we speculate that most patients with alcoholic chronic pancreatitis and pseudocysts will be symptomatic.

In one study, 66% of surgical procedures for alcoholic chronic pancreatitics were performed because the patients had pseudocysts associated with Type B pain.(9) Of these patients, 70% had lasting (>5 years) pain relief post-operatively. Surgery in patients with pseudocysts is usually directed not only at the pseudocyst (cyst enterostomies) but also at the underlying disease and may include main duct drainage procedures (lateral pancreaticojejunostomy) and/or resection (especially of the distal pancreas if this is preferentially involved).

In addition to surgery, both percutaneous and endoscopic techniques are available for treating pseudocysts nonoperatively. There are no prospective trials comparing the outcome of these modalities with each other or with surgery. Local expertise is often the deciding factor as to which of the three techniques are used. In our view, surgery should be reserved for cases in which endoscopic methods are not feasible or are unsuccessful. Surgery, of course, also is necessary to treat complications arising from a percutaneous or endoscopic approach.

Percutaneous techniques require access to the pseudocyst without having to traverse liver, spleen or loops of bowel. The procedure is performed by a radiologist, usually with CT guidance. The technique probably should be avoided in patients with known duct disruption or dislocated duct syndrome, or multi-loculated cysts or multiple cysts. The catheter is removed once drainage flow rates have decreased to 5-10 ml/day. The major disadvantage of the technique is that prolonged drainage (~1 month) is commonly required. External fistulas, infection and failures are potential complications.

Endoscopic techniques include a transampullary approach and a transmural approach from either the stomach or duodenum. No hard and fast rules apply as to which technique to use. In general, pseudocysts remote from the gastric or duodenal wall; cysts <6 cm; cysts associated with duct disruptions; or cysts that are in communication with the pancreatic duct are drained via the transampullary method when feasible. Even multiple large pseudocysts in communication with the pancreatic duct have been successfully treated with transampullary drainage only. High-grade downstream pancreatic strictures or obstructions from pancreatic duct calculi may result in unsuccessful attempts at transampullary drainage. The technique includes an ERCP, a pancreatic duct sphincterotomy and insertion of pancreatic duct stents to bridge areas of stenosis and duct disruptions. The distal end of the stent is sometimes placed into the pseudocyst if there is ductal communication.

Endoscopic cyst gastrostomies or duodenostomies (transmural cyst drainage) are performed with and without the aid of EUS. Visible bulges into the stomach or duodenum allow safe procedures without EUS. Nonetheless, EUS is increasingly utilized prior to transmural drainage to evaluate cyst architecture to ensure that the lesion is a cyst and that gastric varices are absent at a potential gastric wall puncture site. EUS is also helpful to evaluate the cyst contents (e.g. for particulate contents, especially of concern in "acute pseudocysts"), to perform both the puncture of the gastric or duodenal wall and insert stents. The pseudocyst should be within 1 cm of the wall of either the stomach or duodenum. Different techniques are used to penetrate the stomach/duodenal wall - usually either "burning" (electrocautery) through the wall or needle puncture followed by dilation in both cases. One or more 10 French stents are placed into the cyst once access has been obtained. Occasionally, both transampullary and transmural stents are used. In general, large pseudocysts (>5 cm) or cysts associated with complete duct disruption are drained transmurally preferentially. Prophylactic antibiotics usually are used. The stents are left in place for a few weeks to a few months depending on the course and follow up findings on serial imaging by ultrasound or CT scanning. Complications include bleeding, retroperitoneal perforations, infections and failures.

Pancreatic Fistula and Its Major Consequences -- Pancreatic Ascites and Pancreatic Pleural Effusions

Conservative management of pancreatic ascites or pleural effusions is usually the initial approach. Such management includes total parenteral nutrition in order to decrease pancreatic exocrine secretions as much as possible. Additional attempts to decrease pancreatic secretion can be attempted with the use of octreotide. Repeated paracentesis to effect serosal apposition and sealing of the fistula is of doubtful benefit and probably simply depletes the patient of protein. Thoracentesis or placement of a chest tube may be more helpful, especially if the effusion is of large volume and causing dyspnea. Although ~50% of patients fail conservative treatment (~10% of patients may die), such treatment is a reasonable approach if limited to 2-3 weeks only and if it seems that improvement is occurring.

Endotherapy may be effective for both external and internal pancreatic fistula. It is uncertain as to whether endotherapy should be used very early after a diagnosis of pancreatic fistula. One concern is that endotherapy may cause complications, for example, infection. Thus, we prefer to advocate a conservative approach initially. Endotherapy is similar to that described for pseudocysts (see above). The principle is to try and bridge a ductal disruption with a pancreatic duct stent. If this can be accomplished, the fistula resolves (as does the ascites and/or pleural effusions). If endotherapy fails, surgery (decompression and/or resection) is usually the next step.

Bile Duct Strictures

Two issues drive treatment considerations. Is the stricture causing symptoms or overt signs (pain, pruritus, jaundice, cholangitis)? Is the stricture causing (or likely going to cause) progressive liver disease (obstructive fibrosis/secondary biliary cirrhosis)? Remarkably, biliary diversion not only prevents progression of liver disease but may result in regression of existing hepatic fibrosis.(17)

In one center, the second most common (~20%) reason for surgery in chronic pancreatitis was pain thought to be related to bile duct obstruction.(9) Seemingly pain improves after surgery for biliary decompression in these patients. In another center, decompression of the biliary tree (with endoscopic stenting) surprisingly did not lead to significant reduction in pain.(18) Moreover, in many centers, chlolestasis is the primary reason for surgery related to CBD stricture rather than pain per se, although most patients have coexisting pain.

Overall, CBD strictures are usually identified during the evaluation of jaundice or bilirubin elevation or isolated alkaline phosphatase elevation. Management of these cases is not straightforward. For example, the bilirubin and/or alkaline phospatase elevation may result from an "acute flare" of acute pancreatitis on chronic pancreatitis and may resolve as inflammation and edema from an acute exacerbation resolves. At this stage, invasive imaging or stenting are not performed, as patients may need to be followed for a few weeks to assess whether mild bilirubin elevation will normalize. If the bilirubin remains elevated, patients are encouraged to undergo a surgical biliary diversion to prevent (and reverse) secondary liver damage. Patients with isolated elevations of the alkaline phosphatase (i.e., normal bilirubin values) and biliary strictures are encouraged to undergo liver biopsy to determine whether hepatic fibrosis is present versus alcoholic liver disease. The presence of hepatic fibrosis prompts surgical decompression of the biliary tree. The absence of fibrosis reassures patient and clinician that observation with repeat liver testing every 6 months is appropriate. An elevation in the bilirubin prompts surgery.

Endoscopic treatment with metal stents or increasing numbers (over time) of plastic stents in strictured distal common bile ducts from chronic pancreatitis have been found to be efficacious in the short-term. However, we share the opinion of others that such treatment is inappropriate for the majority of patients with chronic pancreatitis.(19) This is a 'benign' disease, multiple procedures may need to be performed and the long-term outcome of endoscopic techniques is unpredictable. Instead, we support surgical diversion, which may consist of a choledochal duodenostomy or a Roux-en-Y jejunal bypass.

Splenic Vein Thrombosis

Splenectomy cures the sinistral portal hypertension and eliminates gastric varices. Usually splenectomy is performed only after acute gastric variceal bleeding has become manifest.

Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma

Surgery (for curative intent or palliation), chemotherapy and radiation, as well as endoscopic procedures for palliation, are all considerations for therapy of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. However, these topics are beyond the scope of this review.Summary

Chronic pancreatitis is a difficult disorder for both diagnosis and management, and most commonly results from alcohol abuse. However, there are less common disorders including genetic diseases that should be considered. In patients with advanced disease, steatorrhea and abnormalities on routine imaging tests allow an unambiguous diagnosis. In patients with early disease associated with pain only, the diagnostic approach can be challenging, as indicated in this review.

Treatment of the pain of chronic pancreatitis for most patients is limited to pain medications. There are some patients especially women with idiopathic chronic pancreatitis whose pain will respond to high doses of oral pancreatic enzymes. In some patients with severe and debilitating pain, options such as nerve blocks and pancreatic surgery need consideration.

Treatment of the exocrine and endocrine insufficiency of advanced disease requires continual monitoring of the clinical response. Supplementation, especially with vitamin D and calcium, is appropriate. Because of the "brittle" nature of the diabetes mellitus of endocrine insufficiency (i.e., inability to mount a vigorous response to hypoglycemia), control of glucose should not be "tight."

Continuous and careful clinical monitoring of these patients is also necessary for early detection of complications such as pseudocysts, fistulas, bile duct strictures and carcinoma.