Course Authors

J. Douglas Bremner, M.D.

Dr. Bremner is Professor of Psychiatry and Radiology at the Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia, and author of You Can’t Just Snap Out Of It: The Real Path To Recovery From Psychological Trauma: Introducing the START NOW Program.

Within the past 12 months, Dr. Bremner has no conflicts of interest relevant to this activity.

Albert Einstein College of Medicine, CCME staff, and interMDnet staff have nothing to disclose relevant to this activity.

Estimated course time: 1 hour(s).

Albert Einstein College of Medicine – Montefiore Medical Center designates this enduring material activity for a maximum of 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

In support of improving patient care, this activity has been planned and implemented by Albert Einstein College of Medicine-Montefiore Medical Center and InterMDnet. Albert Einstein College of Medicine – Montefiore Medical Center is jointly accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME), the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE), and the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC), to provide continuing education for the healthcare team.

Upon completion of this Cyberounds®, you should be able to:

List the effects of stressors such as combat or childhood abuse on the brain and cognition, and the implications for health, public policy, rehabilitation and psychiatric treatment;

Describe studies that show smaller volume of the hippocampus in posttraumatic stress disorder with associated cognitive memory deficits and explain theories behind these findings and effects of treatment on memory and the hippocampus;

Discuss how dysfunction of medial prefrontal cortex and increased function in the amygdala may contribute to symptoms of stress-related disorders like PTSD, and the effects of treatment on these brain areas;

Apply treatments for stress-related disorders, including PTSD and depression, that have been shown to have efficacy for these conditions.

Childhood abuse, motor vehicle accidents, assault, and other psychological traumas and stressors represent a major public health problem in our society today. Psychological trauma, defined as threat to life or integrity of yourself or someone close to you, affects over half of the U.S. population at some time in their lives.(1)(2) Childhood sexual abuse alone affects 16% of women (about 40 million) in the U.S.A.(2)

Epidemiology

The most common cause of post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in women is childhood sexual abuse, while in men the most common cause is physical assault.(1) Other causes of PTSD include motor vehicle accidents, combat and natural disasters.

Symptoms of PTSD include intrusive memories, nightmares, flashbacks, feeling worse with reminders, increased physiological arousal with reminders, avoiding reminders and trying to avoid thinking about the trauma, distorted negative conditions, increased startle and vigilance, social impairment and problems with memory and concentration.

Depression and anxiety are also important, frequent, secondary symptoms of PTSD.

All these symptoms are the result of the effects of psychological trauma on the brain and stress-responsive systems, and they can be reversed with treatment.(3)(4)

Neuropathophysiology

Studies in animals show that stress causes reduced neuronal branching in the hippocampus and an inhibition of neurogenesis, the ability to grow new neurons. These effects can be blocked or reversed with treatment including antidepressants like paroxetine and fluoxetine, or the anti-epilepsy medication, phenytoin.

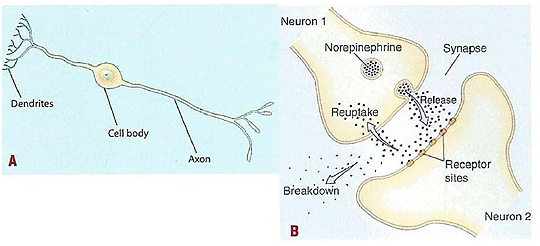

Figure 1. The Human Neuron.

(A) A long axon, at the end of which neurotransmitters are released into the space between the cells, called the synapse

(B) neurotransmitters travel through the synapse, where they attach to an adjacent neuron's dendrites, which are branching ends of the neuron that receive signals from adjacent neurons. Reuptake sites (where SSRI medications such as Prozac work) "vacuum" the neurotransmitter back into the neuron.

Reprinted with permission from You Can't Just Snap Out Of It, Figure 5, by J. Douglas Bremner, Laughing Cow Books, 2014.

Deprived environment during development also inhibits neurogenesis. This can be reversed by an enriched environment, which has implications for public policy. Finally, running also promotes hippocampal neurogenesis.

(6)Multiple studies have shown that psychological trauma, including childhood abuse, combat, assault or motor vehicle accident, is associated with a smaller volume of the hippocampus, a brain area involved in learning and memory.(6)(7) The psychological trauma is associated with deficits in hippocampal-based learning and memory.

(6)Problems with memory include deficits in declarative memory (ability to remember facts and lists), autobiographical memory, working memory and ability to find your way.(8) The latter problem explains why many PTSD patients get lost on their way to appointments. There is also a failure of activation of the hippocampus in PTSD during the performance of memory tasks, or with finding your way paradigms, as demonstrated by functional brain imaging.(9) Treatment with the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) paroxetine, or phenytoin, reverses the hippocampal and memory deficits seen in PTSD.(10)(11)

The hippocampus mediates many of the symptoms of PTSD. It plays a role in problems with memory and concentration, intrusive memories, flashbacks, dissociation and pathological emotions.(6)

The hippocampus has important links to the medial prefrontal cortex, another brain area that mediates emotion and the stress response, dysfunction of which has also been implicated in PTSD (see below).

Trauma in childhood, including childhood abuse, as well as having parents with mental illness or substance disorders or a history of incarceration, can impair academic achievement.

Childhood trauma also affects other health outcomes, including increasing the risk of developing asthma and cardiovascular disease.(12)(13) Early trauma probably resets the inflammatory and stress-responsive systems, like cortisol and norepinephrine, for life.

In addition to the hippocampus, the amygdala is involved in the pathophysiology of PTSD.(14) The amygdala mediates the learning of the fear response. For instance, if you are attacked by a tiger, the next time you see a tiger you will feel afraid. Your memory of fear is stored in the amygdala. The learning of fear is called fear acquisition. In the classic model of fear learning, a light and shock paired together create a fear response to the light alone. This is a conditioned response, or the acquisition of the conditioned fear response.

Women with childhood, sexual abuse-related PTSD show an increase in amygdala activation compared to normal women during fear conditioning.(15) Other studies showed increased amygdala function during exposure to fearful stimuli such as angry or fearful faces. Increased activity in the amygdala underlies startle, hyperarousal and probably other PTSD symptoms.(16)

The medial prefrontal cortex plays an important role in emotion and is, therefore, affected by PTSD. Lesions of this brain area result in an inability to inhibit, or forget, fear-related memories. In the paradigm of fear conditioning described above, with time, fear to the light in the absence of the shock will be extinguished. This is fear extinction, and it is mediated by the frontal cortex inhibiting the amygdala.(17)

Dysfunction of the medial prefrontal cortex in PTSD leads to an inability to inhibit, or extinguish, fear memories. Normal combat veterans can watch a film like Full Metal Jacket and know that there is no risk. Their frontal cortex is inhibiting the primitive fear reaction of the amygdala. PTSD veterans, in contrast, cannot do this. After returning from the battlefield, they literally are unable to turn off their fear response when it is no longer needed.

Brain imaging studies consistently show medial prefrontal lobe dysfunction in PTSD.(18) Exposure of combat-related slides and sounds or scripts of traumatic childhood memories results in decreased function in this area, associated with an increase in fear and PTSD symptoms.(19)(20) Normal traumatized individuals have an increase in function in this brain area when exposed to the same materials.

PTSD patients also show a failure of medial prefrontal activation during the extinction phase of the classic fear conditioning paradigm. We have found, however, that treatment with the SSRI paroxetine results in an increase in medial prefrontal lobe function with exposure to traumatic reminders. Paroxetine treatment is also associated with a decrease in cortisol and heart rate response to stress.(21)

Treatment of Trauma-Related Mental Disorders

Psychotherapy is very useful for trauma-related mental disorders like PTSD and depression. Psychotherapy helps people understand the cognitions, behaviors, and emotions that follow psychological trauma, regain a sense of control and learn coping skills(22) Psychodynamic therapy addresses both the here and now, past events like traumas that have impacted the person, and the nature of the relationship with the therapist.

Psychodynamic therapy is based on the assumption that there are unconscious forces (often linked to the trauma) that contribute to negative emotions and behaviors. Interpersonal therapy focuses on the interactions and behaviors with family and friends, emphasizing the goal of improving communication skills and increasing self-esteem. In cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), negative cognitions (e.g., negative view of the world in PTSD and pessimistic thinking in depression) are addressed and the logical basis for these thought patterns is examined.

Both psychotherapy and medications (see below) are effective for PTSD and the associated depression, and often the best approach is a combination of the two.

Stress management techniques are also useful for PTSD. These include yoga, meditation, deep breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, and mindfulness-based stress reduction.

Antidepressant medications have been shown to be efficacious for PTSD. Antidepressants act on the serotonin, norepinephrine and other neurotransmitter systems in the brain. Antidepressants bind to proteins called transporters and receptors that signal the action of the neuron or take the neurotransmitter out of the synapse and back into the neuron.

Tricyclic antidepressants increase norepinephrine and serotonin in the synapse. Tricyclics were the first class of medications found to work for the treatment of depression. They include doxepin (Sinequan), imipramine (Tofranil), amoxapine (Asendin) and amitriptyline (Elavil). Side effects include anticholinergic side effects such as blurred vision, dry mouth, constipation, memory problems, confusion, sexual dysfunction and decreased urination. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) block, as their name implies, reuptake of serotonin into the synapse. They include paroxetine (Paxil), fluoxetine (Prozac, Sarafem), escitalopram (Lexapro), fluvoxamine (Luvox), citalopram (Celexa) and sertraline (Zoloft).

Table 1. Medications for PTSD and Secondary Symptoms (e.g., Depression and Anxiety).

| Drug | Use | Common, benign side effects | Serious side effects | Life-threatening side effects | Reasons not to take |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRI) Low Risk | |||||

| Paroxetine (Paxil) | Major depression, panic, OCD, PTSD, GAD | Nausea, diarrhea, headache, insomnia | Decreased libido, akithisia | Suicidal thoughts, mood swings with dose change | Allergic reaction, MAOI |

| Sertraline (Zoloft) | Major depression, panic, OCD, PTSD, GAD | Nausea, diarrhea, headache, insomnia | Decreased libido, akithisia | Suicidal thoughts, mood swings with dose change, bleeding | Allergic reaction, MAOI |

| Fluoxetine (Prozac)) | Major depression and OCD | Nausea, diarrhea, headache, insomnia | Decreased libido, akithisia | Suicidal thoughts, mood swings with dose change | Allergic reaction, MAOI |

| Citalopram (Celexa) or Escitalopram (Levapro) or Fluvoxamine (Luvox)Paroxetine (Paxil) | Major depression | Nausea, diarrhea, headache, insomnia | Decreased libido, akithisia | Suicidal thoughts, mood swings with dose change | Allergic reaction, MAOI |

Abbreviations: OCD, obsessive compulsive disorder; GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; MAOI, monoamine oxidase inhibitor;

Reprinted with permission from You Can't Just Snap Out Of It by J. Douglas Bremner, Laughing Cow Books, 2014.

While all of the SSRIs have been approved by the FDA for the treatment of depression, the FDA has specifically also approved paroxetine (Paxil) and sertraline Zoloft) for the treatment of PTSD. Compared to the tricyclics, SSRIs produce fewer side effects. For this reason, patients treated with SSRIs drop out less frequently than patients who are being treated with tricyclics, although SSRIs have not been shown to have greater efficacy.(23) Patients with mild or moderate depression do not have clinically meaningful responses to antidepressants, while those with severe depression have more substantial responses.

Side effects of SSRIs include insomnia, nausea, diarrhea, headache, and agitation. SSRIs can be associated with considerable sexual dysfunction. If this becomes a problem, medications in different classes, such as bupropion (Wellbutrin) can be substituted. SSRIs can also cause akathisia (feelings of internal restlessness), although these symptoms can be treated with benzodiazepines. All antidepressants are associated with increased risk of suicidal thinking.(24) This is not common, however, and seems to be associated with quick changes in dosage or abrupt discontinuation.

Norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (NRIs) block reuptake of norepinephrine into the synapse. These antidepressants include desipramine (Norpramin) and nortriptyline (Aventyl, Pamelor). Like the SSRIs, they have fewer anticholinergic side effects than the tricyclics.

Antidepressants with a dual reuptake inhibition of serotonin and norepinephrine (SNRIs) include venlafaxine (Effexor) and duloxetine (Cymbalta). They have a slightly better efficacy than SSRIs but have a higher tendency toward suicidality. Side effects include headache, dizziness, constipation, dry mouth and changes in sleep. A serotonin syndrome, with restlessness, shivering and sweating, is more rare.

Antidepressants with alternative mechanisms of action include bupropion (Wellbutrin), mirtazapine (Remeron), trazodone (Desyrel) and maprotiline (Ludiomil). Bupropion primarily acts on dopamine systems. Side effects include increased blood pressure, weight loss and restlessness. Mirtazapine is a quatrocyclic antidepressant that blocks pre-synaptic noradrenergic alpha-2 receptors and other receptors. Side effects include fatigue, sweating and shivering, tiredness, strange dreams, weight gain, dyslipidemia, anxiety and agitation. Trazodone and maprotiline have fewer anticholinergic side effects than other antidepressants. Desyrel can rarely cause priapism (extended painful erection that requires emergency treatment).

Benzodiazepines act on the GABA-benzodiazepine receptor complex to stimulate release of the inhibitory neurotransmitter, GABA. They are used for the treatment of anxiety, a frequent secondary symptom associated with psychological trauma. Benzodiazepines prescribed for anxiety and/or insomnia include alprazolam (Xanax), clonazepam (Klonopin), temazepam (Restoril), oxazepam (Serax), lorazepam (Ativan), chlordiazepoxide (Librium), clorazepate (Tranxene), diazepam (Valium), among others. They differ in time of onset of action and duration of effect. Side effects from benzodiazepines include daytime drowsiness, dizziness, light-headedness, memory problems and increased risk of motor vehicle accidents.

PTSD and Insomnia

Insomnia is another common symptom associated with psychological trauma. Some of the benzodiazepines are used in the treatment of insomnia including temazepam. In more common use today are the "Z" drugs -- zaleplon (Sonata), zolpidem (Ambien), zopiclone (Imovane) and eszopiclone (Lunesta). They also act on specific subsets of the GABA receptor, although they were marketed as "non-benzodiazepine" medications with the claim that they were associated with less dependence and fewer side effects.

Studies have not shown the "Z" drugs to be more effective or safe than the benzodiazepines for the treatment of insomnia, and no differences among the various "Z" drugs for safety or efficacy have been demonstrated.(25) Side effects for all of these medications include memory impairment, drowsiness and dizziness. An increased risk of road traffic accidents was also seen with zopiclone. Half-life of these medications varies -- zaleplon is one hour, zolpidem 2.5 hours and eszopiclone 6 hours.

Another medication used for the treatment of insomnia is rozerem (Ramelteon), a melatonin receptor agonist. Side effects include nausea, headache, drowsiness, fatigue, dizziness, and more rarely diarrhea and depression.

Buspirone (Buspar) is also used to treat anxiety. It causes fewer sedating effects and effects on memory than the benzodiazepines. Buspirone is an agonist of the serotonin 1A receptor. Side effects include nausea, headache and light-headedness.

Other Therapies

St John's wort (Hypericum perforatum) is an herb that has been used for the treatment of depression, a frequent secondary symptom seen in PTSD. St. John's wort has actions on the brain, including monoamine oxidase inhibition, serotonin reuptake inhibition and effects on sigma receptors. Some studies have shown that St. John's wort is better than placebo for the treatment of depression, although studies have been highly variable in their results.(26) Omega-3 fatty acids, including eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid, have been promoted for treatment of depression. Studies of efficacy have had mixed results.(27)

Kava is an extract of the roots of the Polynesian plant Piper methysticum and is advocated for the treatment of anxiety, another frequent secondary PTSD symptom. Although some controlled trials have shown it to work for anxiety,(28)(29) it can have side effects, including dry mouth, dizziness, stomach problems, diarrhea, drowsiness, depression and, more rarely, liver failure. Because of the risk of liver failure, Kava is not recommended for the treatment of mood disorders.

Exercise produces a clinically significant improvement in depression.(30)(31) In general, studies have found larger effect sizes in clinically depressed samples than in non-clinical samples. A half hour a day of exercise six days a week is an effective treatment for the mild to moderate depression that may accompany PTSD. Exercise may also complement the effects of antidepressant medication.

PTSD and Mild Traumatic Brain Injury

Memory problems in PTSD patients has made it difficult to differentiate PTSD from mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) in returning soldiers from Iraq and Afghanistan, since many soldiers have both head impact and trauma exposure. Symptoms of post-concussion syndrome, including headaches and problems with memory and concentration, overlap with PTSD. The fact that mTBI is not associated with brain damage visible on imaging complicates things.

Alterations in memory form an important part of the clinical presentation of patients with PTSD. PTSD patients report deficits in declarative memory (remembering facts or lists, as reviewed below), fragmentation of memories (both autobiographical and trauma-related) and dissociative amnesia (gaps in memory that can occur for minutes to days and are not due to ordinary forgetting).

Clinical and Public Policy Implications of the Effects of Psychological Trauma on Cognition and the Brain

Studies on memory and the brain may shed light on areas of clinical relevance to the treatment of PTSD. The hippocampus plays an important role integrating different aspects of a memory at the time of recollection. Hippocampal dysfunction following exposure to childhood abuse may lead to distortion and fragmentation of memories.(32) For instance, in an abused patient who was locked in the closet, there is a memory of the smell of old clothes but no affective memory or visual memory of being in the closet.

Psychotherapy may facilitate associations that bring all of the aspects of the memory together, or there may be a related incident that triggers the recollection of the whole event. Finally, successful treatment (whether medication or psychotherapy-related) may promote medial prefrontal function, diminishing the fear reaction to the memory, which allows it to come fully into consciousness.

Childhood trauma and effects on cognition and the brain have important implications for public health policy. Children in inner cities often witness violent crimes in their neighborhoods and families, and can be exposed to other traumas such as accidents, parental incarceration or childhood abuse. Effects on brain and cognition early in life may put children at a disadvantage that they are not able to overcome later in life. As an illustration of this, traumatized Beirut adolescents with PTSD had deficits in academic achievement, compared to non-traumatized adolescents and traumatized adolescents without PTSD.(33)

Summary

We have reviewed the effects of childhood abuse and other traumas on cognition and the brain. These studies show that trauma related to combat, childhood abuse, or other events leads to dysfunction of a brain network involved in memory that includes the hippocampus, amygdala and medial prefrontal cortex. These changes underlie the symptoms of PTSD.

Altered hippocampal function leads to problems with new learning and memory and underlies flashbacks and intrusive memories. The amygdala over-encodes fear and underlies symptoms of increased startle and hypervigilance. Medial prefrontal dysfunction is responsible for the failure to inhibit intrusive memories or fear responses to reminders, ultimately producing avoidance of the reminders.

Successful treatment — with either psychotherapy or medications — reverses these changes. Understanding PTSD and the effects of treatment from a neuroscience perspective represent a useful model for both the mental health treater as well as the client in recovery. Clients can use these models to provide an objective and blame-free approach to charting their own recovery from psychological trauma.(34)

For more information on PTSD, especially for your patients, please see Dr. Bremner's new book You Can't Just Snap Out Of It: The Real Path To Recovery From Psychological Trauma: Introducing the START NOW Program.