Myocardial Infarction

Course Authors

Richard Josephson, M.S., M.D., and Sri K. Madan Mohan, M.D.

Dr. Josephson is Professor of Medicine Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine. Director Cardiac Intensive Care Unit and Director Cardiovascular & Pulmonary Rehabilitation at Harrington Heart & Vascular Institute and Dr. Mohan is Assistant Professor of Medicine, ?Chief Quality Officer and ?Program Director, ?Harrington Heart & Vascular Institute?, Case Western University School of Medicine, Cleveland, OH.

Within the past 12 months, Drs. Josephson and Mohan report no commercial support.

Albert Einstein College of Medicine, CCME staff, and interMDnet staff have nothing to disclose.

Estimated course time: 1 hour(s).

Albert Einstein College of Medicine – Montefiore Medical Center designates this enduring material activity for a maximum of 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

In support of improving patient care, this activity has been planned and implemented by Albert Einstein College of Medicine-Montefiore Medical Center and InterMDnet. Albert Einstein College of Medicine – Montefiore Medical Center is jointly accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME), the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE), and the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC), to provide continuing education for the healthcare team.

Learning Objectives

Upon completion of this Cyberounds®, you should be able to:

Discuss the role of medications and therapies in the post-MI patient

Counsel the patient regarding post-MI risk and activity

Identify and address the problem of non-adherence to medications.

This presentation may include discussion of commercial products and services.

Significant progress has been made in the primary and secondary prevention of myocardial infarction (MI). Nevertheless, there has been only a modest reduction in the incidence of myocardial infarction and it remains a leading cause of death.

Much effort and energy have been spent on the timely recognition and management of acute MI, in particular emergent reperfusion therapy. This Cyberounds® will focus on the non-emergent and subacute management of MI. We will also address some issues at discharge and highlight the recently identified hospital to home transition. The importance of these measures is reflected in the several guidelines and updates published by the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA).(1)(2)(3)

|

Case Vignette Ms. T is a 64-year-old female with diabetes mellitus (DM), hypercholesterolemia and rheumatoid arthritis. Her mother died of a myocardial infarction at age 65. She presents with a two-day history of accelerating angina culminating in rest pain and myocardial infarction. She seeks attention five hours after severe unrelenting pain and is found to have a large, inferolateral, ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). Ms. T undergoes primary stenting of a dominant right coronary artery. On Day 2 she is in mild congestive heart failure (CHF) and an echocardiogram shows an ejection fraction (EF) of 30% with an extensive inferolateral wall motion abnormality. |

Treatment

Anti-Platelets

Aspirin therapy is the cornerstone of antiplatelet therapy after MI. The ISIS 2 study(4) randomized patients to aspirin and streptokinase in a 2X2 factorial design. Aspirin reduced cardiac mortality by 23%. Current recommendations: 162-325 mg P.O. of aspirin immediately and 81-325 mg P.O. qd indefinitely.

Aspirin therapy is the cornerstone of antiplatelet therapy after MI.

With the arrival in the last few years of newer P2Y12 inhibitors, clinicians now have more antiplatelet options. These agents, when used in conjunction with aspirin, are referred to as dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT). In general, more potent antiplatelet therapies are associated with a lower risk of recurrent ischemic events but at the cost of increased hemorrhage.

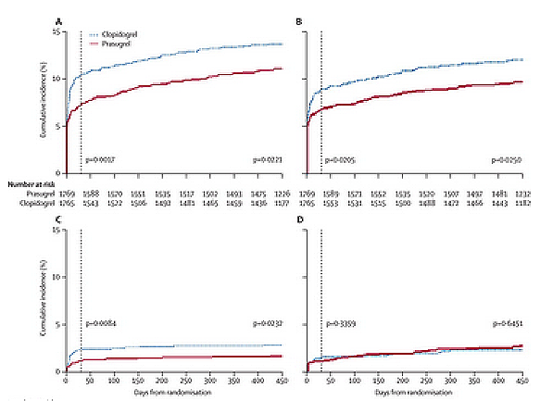

The CLARITY-TIMI 28(5) studied patients who received fibrinolysis. The addition of clopidogrel with a loading dose of 300 mg was associated with a 20% reduction in primary end point. ACC guidelines recommend the use of clopidogrel for a 12-month period post-MI. There are little data regarding the use of prasugrel or ticagrelor in patients who undergo thrombolysis. Reperfusion by percutanteous intervention (PCI) is the preferred method of opening occluded arteries. However, should this not be feasible in a timely manner, thrombolytic agents such as reteplase are used.The TRITON-TIMI 38(6) compared prasugrel with clopidogrel in acute coronary syndrome (ACS) patients undergoing PCI. A relative risk reduction of 19% was observed with prasugrel. This benefit was not seen in patients <60 kg, >75 years or who had a history of stroke. Based on this observation, the ACC recommends the use of prasugrel for a period of one year after MI as an alternative to clopidogrel. Consideration for continued use after one year should be given to patients who receive a drug-eluting stent.

Figure 1.

Prasugrel vs. Clopidogrel in STEMI Patients.

Source: The Lancet: Prasugrel compared with clopidogrel in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-elevation myocardial infarction (TRITON-TIMI 38): double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Reproduced with permission.

The PLATO study(7) compared ticagrelor and clopidogrel in patients undergoing PCI. Ticagrelor yielded a 13% reduction in composite endpoint in the STEMI subpopulation. Similar to the other P2Y12 inhibitors, ticagrelor should be prescribed for a period of one-year post-MI as an alternative to clopidogrel. Consideration for continued use after one year should be given to patients who receive a drug-eluting stent.

It is important to consider the choice of stent and dual antiplatelet therapy in this patient population. Factors including cost, compliance and possible need for surgery should be borne in mind. This is, not uncommonly, difficult in the emergent situation of STEMI.

Table 1. Currently Available P2Y12 Inhibitors.

| Clopidogrel | Prasugrel | Ticagrelor | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Load | 300-600 mg | 60 mg | 180 mg |

| Maintenance | 75 mg daily | 10 mg daily | 90 mg bid |

| Avoid if... | Prior CVA/TIA Weight <60 kg Age ≥75 |

Prior ICH |

Legend: CVA – cerebrovascular accident; TIA – transient ischemic attack; ICH – intracranial hemorrhage

Beta Blockers

Beta blockers have been extensively studied in the management of MI. They appear to be useful because they lower oxygen demand, reduce the frequency of arrhythmias and exert positive effects on remodeling. Several studies including ISIS 1(8) and MIAMI(9) demonstrated that early I.V. and continued P.O. use of beta blockers decreased post- MI mortality.

Even greater benefit was seen among higher risk patients. Older patients and those with history of MI, hypertension, angina, diabetes and CHF or LV dysfunction are recognized to be at a higher risk. A meta-analysis of over 50,000 unselected patients revealed a 23% reduction in death.(10)

More recently, researchers studied the effects of beta blockers on the hemodynamic stability of post-MI patients. In the COMMIT/CCS2 trial early I.V. use in unstable patients was associated with a reduction in reinfarction, but an increase in cardiogenic shock, with no overall mortality benefit.(11) Therefore, it is recommended that early I.V. use of beta blockers be limited to patients with hypertension, tachycardia and continued pain and with no contraindications. Contraindications include hypotension (SBP<120 mm Hg), decompensated heart failure, bradycardia (HR<60 bpm) and conduction disturbances. Reactive airways disease is a non cardiovascular relative contraindication.

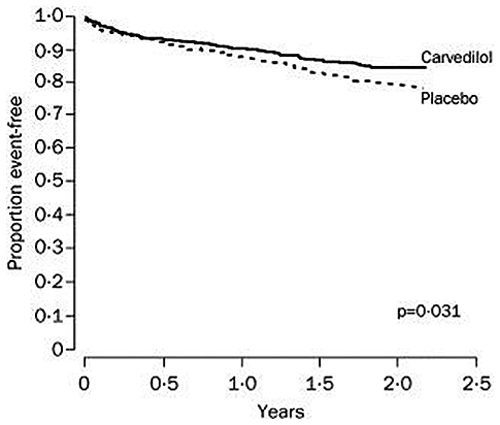

The CAPRICORN study evaluated the utility of carvedilol in post-MI patients with reduced EF (<40%).(12) At 15 months, the study reported a 23% reduction in all-cause mortality.

Figure 2.

Carvedilol Post-MI.

Source: The Lancet: Effect of carvedilol on outcome after myocardial infarction in patients with left-ventricular dysfunction: the CAPRICORN randomised trial. Reproduced with permission.

Patients should be evaluated daily and oral beta blockers initiated as early as possible. The general approach is to start with a low dose of beta blocker and titrate up to the target dose. Beta blockers are potentially hazardous in decompensated heart failure and treatment of volume overload often precedes beta blocker initiation.

The target dose for metoprolol succinate is 200 mg P.O. qd and for carvedilol 25 mg P.O. bid. Upward titration is often incomplete in the current era of short inpatient hospitalizations. Resting- and exercise-associated heart rate (which may be examined via patient ambulation in office), as well as the presence of possible side effects, should guide dose titration. The goal is to up-titrate to the maximal tolerated dose over a 4 to 6 week period to achieve a resting heart rate in the 60s.

Table 2. Commonly Used Beta Blockers.

| Metoprolol Succinate | Carvedilol | |

|---|---|---|

| Antagonist | Beta 1 selective | Beta and alpha 1 |

| Target dose | 200 mg qd | 25 mg bid |

| Preferred in specific populations | Prone to bronchospasm, hypotension | Diabetes mellitus |

After gentle diuresis, we initiated carvedilol in this patient.

ACE Inhibitors

Patients with reduced EF and/or CHF should receive an ACE inhibitor in the absence of contraindications. Contraindications include allergies, renal dysfunction or hyperkalemia and hypotension.

Patients with reduced EF and/or CHF should receive an ACE inhibitor in the absence of contraindications.

ACE inhibitors improve remodeling, reduce afterload and lessen local tissue effects. Several studies reported a mortality benefit with the initiation of ACE inhibition post-MI. The SAVE study demonstrated a 19% reduction in mortality and an even greater reduction in clinical CHF incidence in patients with reduced EF.(13) Reduced mortality has been reproduced in several studies(14) resulting in the recommendation to initiate ACEi therapy within the first 24 hours of MI. If a patient has borderline hypotension, it is necessary to carefully monitor ACEi dosing in order to avoid precipitating shock.

Attempts at using I.V. enalaprilat early upon presentation in CONSENSUS II(15) resulted in increased mortality. Early I.V. use is not recommended.

Several studies including OPTIMAAL(16) and VALIANT(17) demonstrated the equivalence of ACE inhibitors and AR blockers in this clinical situation. Thus ARBs can be used in ACEi-intolerant patients.

We recommend the initiation of captopril and up-titration in the hospital prior to conversion to a long-acting ACE inhibitor at discharge. In hemodynamically stable patients it is acceptable to start long-acting ACEi directly.

Statin Therapy

LDL and HDL levels fall after MI. Thus, there is controversy regarding the ideal time after ACS that will result in valid results. The ACC STEMI guidelines recommend that lipids be measured in the first 24 hours. The LUNAR trial,(18) however, demonstrated that LDL and HDL levels in the first four days after ACS essentially did not vary and that any values obtained in the first few days could be used. Note should be made that in the LUNAR study LDL was measured directly, as opposed to an indirect calculation that may be significantly affected by variations in triglyceride levels.

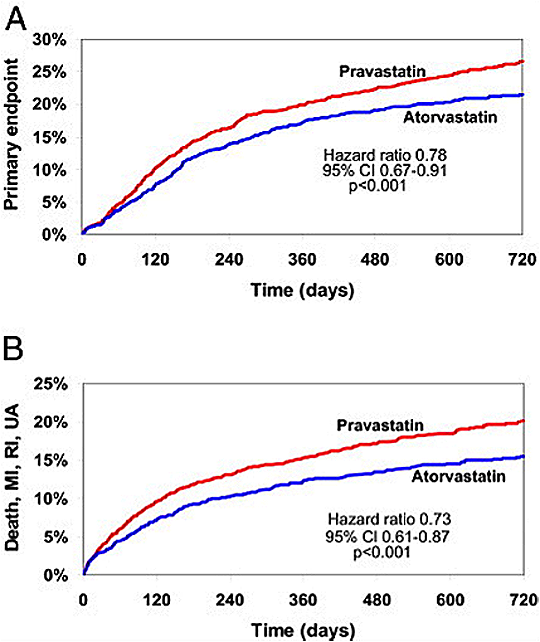

The PROVE IT – TIMI 22 trial(19) assessed the value of intensive statin therapy (atorvastatin 80 mg/day) vs. less intense therapy (pravastatin 40 mg/day). Researchers found a significant reduction in primary endpoint with high-dose atorvastatin, primarily driven by a reduction in recurrent ischemia. All-cause mortality also decreased but not significantly. Similarly, the MIRACL study(20) demonstrated a reduction in primary endpoint (14.8% vs. 17.4%), once again driven by fewer instances of recurrent ischemia.

Figure 3.

Intensity of Lipid Lowering.

Source: Journal of the American College of Cardiology: Effect of Intensive Statin Therapy on Clinical Outcomes Among Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for Acute Coronary Syndrome: PCI-PROVE IT: A PROVE IT-TIMI 22 (Pravastatin or Atorvastatin Evaluation and Infection Therapy-Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction 22). Reproduced with permission.

The literature offers limited data on the use of statins in patients with low baseline LDL levels. A small retrospective study showed a significant reduction in mortality and morbidity with the use of statins.(21) Study authors attributed these statistical improvements to purported pleiotropic benefits including plaque stabilization, anti thrombotic and positive effects on endothelial function.

Several studies, including CHAMP,(22) demonstrated that the early initiation of statins prior to discharge is associated with a reduction in clinical events and an increase in compliance. The authors, therefore, start high-dose statins prior to discharge in all patients with a goal LDL of less than 70 mg/dl. The use of statins at discharge is used as a metric of quality of care and is one of the core measures.

Measures to increase HDL levels have been disappointing. While increases in HDL were seen with niacin, CETP inhibitors and other drugs, no systematic significant clinical benefit has accrued in the non-MI setting.(23)

We initiated our patient on atorvastatin 80 mg daily and plan to monitor for side effects (principally muscular). Downward titration of statin dosage can be considered in the chronic (>1 year) post-MI phase, guided by LDL levels.

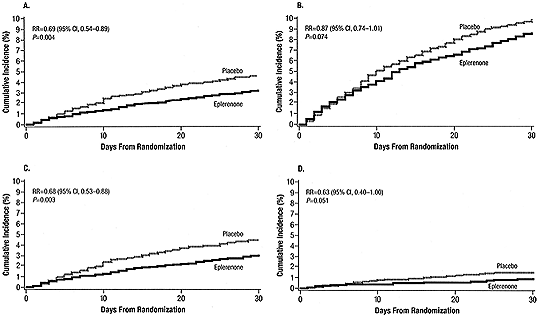

Eplerenone

The EPHESUS trial(24) studied use of eplerenone in the post- MI patient. Patients with reduced EF (<40%), and either CHF or DM were started on eplerenone prior to discharge. Eplerenone was prescribed in addition to baseline medications including ACE inhibitors. Patients with renal dysfunction (creatinine >2.5 mg/dl) and hyperkalemia (>5 meq/L) were excluded. As early as one month (3.2% vs. 4.6%), EPHESUS authors noted a mortality benefit, and this extended out to 16 months. Similarly, there was a reduction in hospitalization due to CHF. This may well be a class effect but spironolactone has not been studied in this scenario.

Figure 4.

Eplerenone Following MI.

Source: Publication: Journal of the American College of Cardiology: Eplerenone Reduces Mortality 30 Days After Randomization Following Acute Myocardial Infarction in Patients With Left Ventricular Systolic Dysfunction and Heart Failure. Reproduced with permission.

We recommend that eplerenone be initiated in-hospital and that the dose be escalated as an outpatient with careful monitoring of renal function and electrolytes. Note that many recommended therapies (e.g., beta blocker, ACE inhibitors and aldosterone antagonists) not only lower blood pressure but also provoke drug-drug interactions. The judicious, often sequential, initiation and titration of these medications is, therefore, recommended. Target doses are not typically achieved in hospital, and outpatient follow-up including continued medication adjustment is required for optimal care.

We recommend that eplerenone be initiated in-hospital.

ICD Implantation

The implantation of ICDs in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy has been associated with a clear survival benefit. However, the timing of such implantation is less clear. Several studies assessing early implantation did not show reduced overall mortality. In the DINAMIT study,(25) patients with recent MI (<40 days) and reduced EF (<35%) underwent ICD implantation. At 30 months, study researchers found no mortality difference between the control and ICD implant groups. Possible explanations for this lack of early benefit include a subsequent improvement in EF in revascularized patients and an early risk of recurrent ischemic events. Guidelines thus recommend the implantation of ICD after 40 days post-MI.

An externally wearable ICD jacket is available. The value of such a strategy in this interim period is currently under investigation.

Cardiac resynchronization therapy in patients with symptomatic CHF, reduced EF and wide QRS (LBBB) has been shown to reduce morbidity and mortality.(26) These devices should be implanted once patients are stabilized on optimal medical treatment for at least several weeks.

Cardiac Rehabilitation: Daily Living Post-MI

Exercise is the core component of cardiac rehabilitation (CR). CR also typically includes regular physical assessment, nutritional and psychological counseling and is typically divided into three phases:

Phase 1 consists of inpatient education targeted at medication use and "survival skills" such as avoidance of driving or heavy labor;

Phase 2 is the core of most patients' experience and usually consists of 36 outpatient sessions (thrice weekly for 12 weeks): supervised exercise and education on a variety of topics including nutrition, medication use and psychological issues (depression, anxiety, coping skills). Exercise consists of both aerobic and strength training phases;

Phase 3 is a long-term supervised exercise and education program designed to maintain and build on achievements of the earlier phases. Commonly, patients will opt to exercise independently or in a public access health club rather than participate in a formal Phase 3 program.

Education is a key component of all three phases.

Considerable data exist reflecting the many benefits of CR. A meta-analysis of ~22,000 patients who underwent CR demonstrated a 20% reduction in total mortality which was seen across all subgroups.(27) Rehab significantly improves functional capacity, sense of well-being, risk factor profile and compliance. Despite these benefits, CR is consistently underused. Evidence suggests that if the CR process is initiated in-hospital, prior to discharge, more patients will participate.

For our Cyberounds®patient, we would recommend evaluation with a physician prior to starting CR phase 2 in order to establish that her CHF is suitably treated and compensated.

Most patients with uncomplicated MI can resume normal activities, including returning to work by two weeks, though there are very limited data. Patients should be encouraged to participate in activities of daily living (ADLs) and other physical activity based on their CR plan. Likewise, the patient can resume car driving 1-2 weeks later.

Sexual activity requires 2–4 METs (metabolic equivalents). We therefore advise patients to abstain for two weeks post-MI, after which the risks of intercourse are lower. And we would personalize our advice based on clinical assessment.

Sexual dysfunction is common after MI. Causes include psychological, physiological and drug-related issues. It is important to proactively address this problem, as some patients are reluctant to mention it. The negative interaction of phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE-5) inhibitors, prescribed for erectile dysfunction, with nitrates is well recognized and their concomitant use (24- to 48-hour window) is contraindicated.

We would advise this patient to abstain from sexual intercourse for a 2-week period. Further advice will reflect the patient's functional capacity and CHF.

Depressive symptoms are very common post-infarction, with female sex and a prior history of depression as major risk factors.

We advise patients to abstain from sex for two weeks post-MI.

The death of our Cyberounds® patient's mother from an infarction at a similar age as the patient potently impacted the patient's mental health and approach to her illness. Unstructured interactions with a patient may hint at depression but data suggest that it is often under-diagnosed. Simple validated questionnaires (PHQ-2) are easily incorporated into hospital and outpatient clinical flow and should be used.(28) Mild depressive symptoms often spontaneously remit, but significant symptoms, suicidality or symptoms that persist for more than several weeks all merit targeted evaluation and therapy. Interestingly, cardiac rehabilitation appears to ameliorate depressive symptoms, a further reason to encourage CR enrollment.(29)

Compliance in the real world is, unfortunately, much poorer than in trials. One in seven patients, for example, stops their thienopyridene (ADP receptor/P2Y12 inhibitors used for their anti-platelet activity) within 30 days of DES implantation. Similarly, in the MI FREEE study,(30) compliance for various prescribed medicines was low — ACEi/ARB (35%), beta blockers (41%) and statins (49%). Compliance for taking all three medications concurrently was 9%. Compliance to medications is often thought to be the patient's responsibility.

There are several possible reasons for the dismal compliance. Side effects, lack of understanding or denial, apathy, complexity, convenience and cost of pharmacotherapies have all been implicated.(31) The physician has a major role in easing these issues. Typically, insurance companies charge copays to reduce utilization of treatments. In the MI FREEE study, medications were provided free of copay costs. Even in the absence of copays there was only a modest increase in adherence to medications. Despite this, the cost of care to the insurance company was less over three years because patients were less likely to have another major cardiac event.

Many observational studies confirm the correlation between non-adherence and poorer clinical outcomes and increased emergency room visits.(32) It is likely that this relationship is stronger than that ascribable to the 'healthy adherer' concept, where compliant patients generally lead healthier lifestyles.(33)

The authors provide education about medications to their patients, prior to discharge, in addition to printed information sheets. Our patients also receive a phone call a few days after discharge, and prior to a follow-up office visit, to review medications and answer any questions they may have. We find it invaluable to include a family member to advocate for and participate in the patient's care.

Conclusions

The subsequent care of the post-MI patient is complex and fraught with challenges. Patients have a significant level of anxiety for recurrent MI and are more aware of chest symptoms. A significant increase in major depression is noted.

We ask patients to modify their life and work styles. Smoking cessation, not discussed in detail, causes great stress. Against this background, treating practitioners must necessarily prescribe many new medications, all of which have demonstrated clinical benefits. But the medications may be expensive and provoke side effects. It is, therefore, paramount that treating physicians understand their indications and associated problems. To underscore their therapeutic importance, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) categorized several of these medications as core measures.(34)