Why all the yelling and screaming? Dealing with agitation in the ED setting.

Course Authors

Michael P. Wilson, M.D., Ph.D., and Gary M. Vilke, M.D.

Dr. Wilson is Director of the Department of Emergency Medicine Behavioral Emergencies Research (DEMBER) lab, and attending physician in UC San Diego Health Systems; Dr. Vilke is Professor of Clinical Emergency Medicine, and Director of Medical Risk Management, UC San Diego Health System, San Diego, California.

Within the past 12 months, Drs. Wilson and Vilke report no commercial support.

Albert Einstein College of Medicine, CCME staff, and interMDnet staff have nothing to disclose.

Estimated course time: 1 hour(s).

Albert Einstein College of Medicine – Montefiore Medical Center designates this enduring material activity for a maximum of 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

In support of improving patient care, this activity has been planned and implemented by Albert Einstein College of Medicine-Montefiore Medical Center and InterMDnet. Albert Einstein College of Medicine – Montefiore Medical Center is jointly accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME), the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE), and the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC), to provide continuing education for the healthcare team.

Learning Objectives

Upon completion of this Cyberounds®, you should be able to:

Discuss safe methods for managing agitated patients in the ED setting

Apply the science of agitation research, including how new approaches allow for faster ED disposition

Apply new expert consensus guidelines to the management of agitation including recommended pharmacological approaches.

This presentation may include discussion of commercial products and services.

|

Case A 23-year-old male with a past history of schizophrenia presents to the emergency department in the company of police after being found on the street corner threatening people. He is paranoid about staff poisoning him. He is talking loudly and is too agitated to sit down in triage, but is still intermittently directable. He reports he has not been taking his psychiatric medications. |

Introduction

Many emergency physicians think agitated patients are some of the simplest individuals to treat -- restrain and then medicate, usually with parenteral preparations -- has been the standard and straightforward protocol.(1)(2)(3)(4)(5) Indeed, in recent emergency medicine (EM) literature, the only apparent controversy with respect to treatment has been which parenteral medication results in the quickest chemical control.

Over the past several years, however, an emerging consensus, originating mostly outside the field of emergency medicine, has criticized the medicated-only protocol for agitated patients as both inhumane and wasteful of emergency (ED) resources.(6)(7) This consensus has called for a bundle of new practices for agitated patients, not unlike a resuscitation bundle in critical care, in which agitated patients are treated with a variety of approaches. Although there is little formal literature on the composition of this bundle, expert consensus agrees that it involves at least the following components:

- Use of standardized agitation scales to objectively measure agitation;

- Attempted verbal de-escalation to calm the patient when this can be done safely;

- Use of medication targeted to the specific etiology of the agitation;

- Use of oral medicines whenever possible;

- Use of second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) rather than first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs) in most situations not involving alcohol intoxication.

??oeSafety first??? starts even before agitated patients arrive in the ED.

In studies of acute agitation, proponents of this new bundled approach have criticized the emergency department's practice of "restrain and sedate."(7) These critics have stated that EM physicians often restrain patients too quickly and wait too long to medicate them, thereby increasing lengths of stay. When patients are finally medicated, the critics contend, the patients are typically administered the wrong kinds or wrong doses of medication, which in turn causes over-sedation and, once again, leads to increased lengths of stay. According to this logic, EM clinicians themselves often contribute to the problems of overcrowding by sub-optimally treating agitated patients in this manner.

Despite this consensus, many emergency departments nationwide have been slow to adopt the use of these recommended measures. Some possible reasons: (1) there are limited data about the use of SGAs in the emergency department, and even more limited data about the use of oral medications for agitation in the emergency setting. Indeed, most SGAs have never been tested in the ED setting against the most common ED regimen of haloperidol and lorazepam;(1)(8)(9) (2) emergency clinicians do not, we've noted, intervene in patients with mild agitation, thus reserving treatment until patients are severely agitated. These patients then require more medication, more frequent restraint, and ultimately use additional ED resources including precious manpower; (3) there is preliminary evidence that the population of agitated patients in the ED is inherently different from the population of agitated patients in the psychiatric inpatient unit,(10)and these patients may require different approaches and different medications.

How ED clinicians should manage agitated patients is therefore somewhat controversial. In this Cyberounds®, we explore the recent science of agitation research. Discussion of key issues and barriers to care for ED patients are presented, together with recent expert consensus guidelines on the issue.

What is agitation?

A 2010 survey of emergency nurses in the Emergency Nurse Association (ENA) study indicated that 54.8% of EM nurses had been physically or verbally abused by patients in the past seven days.(11) Agitation is thus of considerable clinical importance in the acute setting. Although most practitioners use the standard of "knowing it when they see it," agitation has been defined by recent expert consensus guidelines as a "disruption in the physician-patient relationship" which has consequences for the treatment of the patient.(12) These consequences may arise either because staff are threatened, such as reported in the ENA study above, or because it becomes difficult to treat the patient if he or she is severely agitated.

Since agitation is difficult to define, its prevalence is difficult to measure. Many previous studies have therefore investigated staff perceptions of safety. The National Emergency Department Safety Study surveyed staff at 65 U.S. emergency departments and found that more than 25% of ED staff felt safe at work only "sometimes," "rarely" or "never."(13) Other researchers have documented that university police responded, on average, twice daily to violent incidents with a majority of incidents occurring on the night-shift.(14) Anglin and colleagues (1994), however, reported that physicians were not immune from the violence -- nearly 62% of California EM residents indicated they were worried about their safety at work.(15) It is clear that agitation is a significant problem and remains an important ED concern.

How should an agitated patient be approached in the emergency setting?

In a word, "carefully!"(1) No matter what the circumstance, the goals of agitation treatment are the same: calm and protect the patient; calm and protect staff; allow the patient's participation in care to whatever extent possible; and, finally, evaluate and make appropriate disposition of the patient. These goals are not necessarily achieved in order, but all involve boundary-setting, verbal de-escalation if this can be done safely and coordination among ED staff.

"Safety first" starts even before agitated patients arrive in the ED. Staff should have a prepared place for these patients so that they are in a separate room away from potential weapons and sharp objects. An easy way to notify security if the need arises should also be in place.(16)(17)

Once an agitated patient arrives, efforts should be made if possible to ensure that they are physically comfortable. External stimuli such as loud noises should be decreased. Staff assigned to the patient should be trained in verbal de-escalation techniques. Although there is little experimental evidence as to which specific verbal techniques to employ or how long verbal intervention must be in order to be effective (see below), expert consensus agrees that there are few if any side effects to patients from being "talked down," as long as this can be done safely.(18)(19)

Why is the initial approach verbal de-escalation? Aren't clinicians too busy for this?

Much like sepsis care, current expert consensus (mostly outside the emergent setting) states that a variety of strategies is needed to manage agitated patients.(5)(7) Perhaps the key approach is the use of verbal de-escalation, which first attempts to calm the patient with words.19 Although verbal de-escalation is standard in settings outside the emergency department, its use in the ED is not as widespread. This may be for two reasons. First, emergency clinicians often perceive themselves as too busy for verbal de-escalation techniques, and thus opt for early use of medication instead. Second, there is little research about the efficacy of verbal de-escalation types and techniques.

One recent study, however, indicated the potential power of using verbal de-escalation. Isbister and colleagues studied the use of droperidol vs. midazolam in Australian emergency departments.(20) Treating physicians were required to attempt verbal de-escalation before giving either of these medications. As a result, 60 of 223 security calls (26.9%) were lost to the study, since they were calmed to the point of no longer needing medication. An additional 15 patients agreed to oral or IV meds (6.7%). Taken together, approximately one-third of patients screened for this study could not be included after undergoing verbal de-escalation. Thus, verbal de-escalation techniques can be quite powerful, especially in comparison to other treatments in the ED.

Although there are no agreed-upon scripts for verbal de-escalation, recent expert guidelines suggest that clinicians utilize Table 1's principles and Table 2's strategies for verbal de-escalation.(19)

Verbal de-escalation techniques can be quite powerful.

Table 1. Ten Principles of Verbal De-escalation.

- Respect personal space

- Do not be provocative

- Establish verbal contact

- Be concise

- Identify wants and feelings

- Listen closely to what the patient is saying

- Agree or agree to disagree

- Lay down the law and set clear limits

- Other choices and optimism

- Debrief the patient and staff

Source: Janet Richmond, by permission of author.

Table 2. Useful Verbal Strategies in Verbal De-escalation.

| Verbal Approach | Rationale |

|---|---|

| What helps you at times like this? | STRATEGY: Invite the patient's ideas. |

| I think you would benefit from medication. | STRATEGY: Stating a fact. |

| I really think you need a little medicine. | STRATEGY: Persuading. |

| You're in a terrible crisis. Nothing's working. I'm going to get you some emergency medication. It works well and it's safe. If you have any serious concerns, let me know. | STRATEGY: Inducing. |

| I'm going to have to insist. | STRATEGY: Coercing. Great danger, last resort. |

Source: Janet Richmond, by permission of author.

Utilizing these principles, some experts believe that verbal de-escalation can often be accomplished in only a few minutes.

What if the agitation persists or worsens?

For those patients whose behavior continues to deteriorate or who refuse medication, a show of force is typically recommended.(12) This is often termed a "show of concern" instead of a "show of force," in order to differentiate it from police action and emphasize the therapeutic nature of the intervention. A show of concern involves security forces in large numbers who are present outside the patient's room, usually in plain view, in case forcible restraint is required. Oral medication is typically offered at this point.

Forced parenteral medications during such scenarios are often ordered by emergency clinicians. However, this decision is usually made with little forethought and does not often consider the patient's ultimate disposition. Simply being on a psychiatric hold is not sufficient grounds for forcing medication or procedures, unless there is an emergent and overriding reason for doing so.1 Most patients who are at least intermittently directable will take oral medications if prompted to do so. Patients who refuse oral medications or who are violent should be administered IM medication.(25)

According to the latest expert consensus guidelines, the type of agitation should guide the choice of medication.(6) Agitation that is not psychiatric in origin should not be treated with antipsychotics. Hypoglycemia, hypoxia, infection, substance withdrawal and thyroid storm, for instance, should be treated with agents appropriate to these conditions.

Agitation that is not psychiatric in origin should not be treated with antipsychotics.

If a patient's behavior continues to deteriorate, physical restraints may be needed but should be considered as a last resort. Restraints should be used sparingly with minimal force.(21)

What if I must administer medication? Is haloperidol really the best medicine?

Although there a number of different options for pharmacologic treatment of agitation, haloperidol + ativan is the most common antipsychotic combination prescribed in the United States.(3) Haloperidol is a butyrophenone with primary activity at the dopamine 2 (D2) receptor and little activity at other receptor types. According to latest expert consensus guidelines, haloperidol is now second-line for treating agitation of most types (except in patients with alcohol-intoxication) for the following reasons: it carries a black-box warning about use in treating dementia-related psychosis; it lengthens QT intervals, and so is not FDA-approved for IV use; it has a high association with dystonic or other extrapyramidal reactions because it acts at the D2 receptor, located primarily in the basal ganglia; and patients may feel dysphoric after use.(22)(23)(25)(26)

If haloperidol is administered by clinicians, it should be given with an adjunctive medication to reduce side effects. In the largest study of haloperidol in the emergency department, Battaglia and colleagues (1997) randomized 98 psychotic agitated patients in five U.S. emergency departments to either IM lorazepam 2 mg, IM haloperidol 5 mg, or both in combination.(27) Although all patients had a significant reduction in agitation, reduction was more rapid in patients receiving the combination of haloperidol + lorazepam. In addition, the number of extrapyramidal symptoms, defined as dystonia, hypertonia or tremor, was less than in patients receiving haloperidol alone. The authors therefore concluded that if haloperidol is given, it should be prescribed with lorazepam, since the combination is more effective and has a lower risk of side effects.

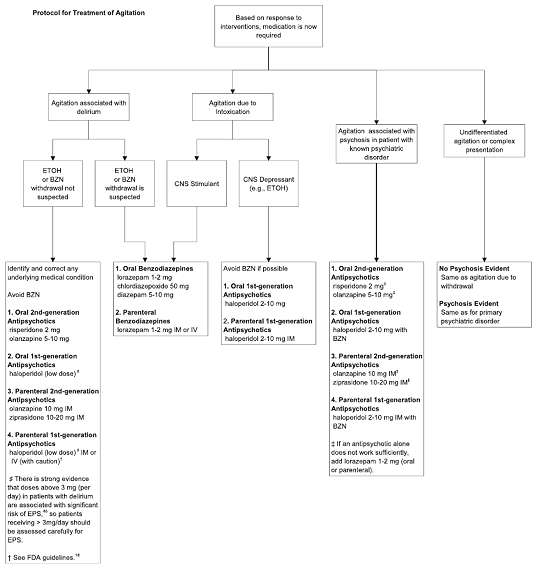

Given both the side effects of haloperidol and the need for administration with adjunctive medications, recent expert guidelines therefore recommend second-generation antipsychotics. These agents have a more complex pharmacological profile, but are preferred in most clinical scenarios not involving alcohol intoxication (see Figure 1)(6):

Figure 1. American Association for Emergency Psychiatry Expert Consensus Guidelines on the Pharmacologic Treatment of Agitation.

Source: Michael P. Wilson, by permission of author.

Why give these medications orally? Have these "experts" ever been in an emergency department?

Many ED providers assume that oral antipsychotics are inappropriate for use in the ED setting, either because they do not work as well as first-generation antipsychotics or because the average agitated patient is "too agitated" for oral medications. These perceptions, however, may result from the fact that, anecdotally, most ED clinicians do not typically treat patients unless they are severely agitated.

Surprising to many ED clinicians, oral SGAs may work just as well as IM injections of haloperidol + lorazepam

Oral SGAs may work just as well as IM injections of haloperidol.

The study with the strongest methodology, performed by Currier et al. (2004), examined a mixture of ED patients and inpatients.(29) In this prospective randomized rater-blinded study, 162 agitated patients were randomized to either 2 mg risperidone and 2 mg lorazepam PO or 5 mg haloperidol and 2 mg lorazepam IM. At all time-points, oral medications were just as effective as IM medications at reducing agitation. However, half as many patients in the first hour who received oral medication fell asleep compared to patients who received IM injections (24% vs 55%, p<.001). As sleeping patients are more difficult to interview and discharge, this likely increases ED lengths of stay.

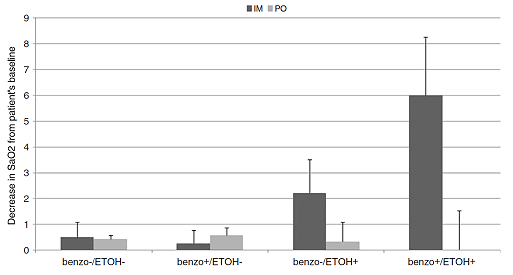

Oral medications in addition to their effectiveness have several other benefits. Use of oral agents is thought to: help maintain a therapeutic relationship; protect staff that would otherwise have to restrain the patient; prevent accidental needle-stick injuries; and may have fewer side effects than IM injections. In a series of studies comparing decreases in oxygen saturations in alcohol-intoxicated patients who received olanzapine and benzodiazepines, the authors found that these decreases were only noted in patients who received IM olanzapine. Patients who received oral olanzapine did not show the same effect (see Figure 2).(30)(31)(32) An inhaled version of a first-generation antipsychotic, loxapine, has been recently approved by the FDA. This has the potential for being an important new treatment for agitation, but is currently limited to use in facilities with the capability of handling bronchospasm.(33)

Figure 2: Decreases in Oxygen Saturation In Alcohol-intoxicated Patients Who Receive Olanzapine: PO v. IM.

Source: Michael P. Wilson, by permission of author.

What is the proper goal of sedation?

Many emergency physicians and staff think that the only properly sedated patient is one who is sleeping, despite multiple appeals from consensus-based expert reviews for "calming" instead of outright sedation.(1)(12)(34) Current guidelines on sedation state that the proper goal of sedation is to "calm" the patient and reduce the risk of violence, while still allowing the individual to participate in their own care as much as possible. More practically, however, patients should be calmed to the point where medical assessment can take place.(36)(37) This is more difficult in sleeping patients, who cannot generally be evaluated by consultants or provide a history.

How and when should a patient be restrained?

Restraint of a patient is encountered frequently in practice, reported up to 3.7% of all patients in one urban ED.(38)(39) The decision to restrain a patient, although monumental in terms of the philosophical and legal implications, is often made with very little thought since many providers assume that a restrained patient is a safe patient. However, this may not be true, as most injuries to staff occur during the restraint process.(40)

The disadvantages of restraint are many. Improperly applied restraints may cause physical and psychological injury to the patient.(41)(42) Philosophically, they do not allow the patient's participation in care.(21)(42) In addition, restrained patients require more nursing resources in order to satisfy Joint Commission requirements for restrained patients: frequent checks, significant charting and documentation by nursing staff. These patients also have increased lengths of stay. In one study of ED psychiatric patients, for example, Weiss et al. (2012) analyzed components of the length of stay, and found that restrained patients stay 4.2 hours longer on average than other psychiatric patients.(43) Thus, reducing restraint use may improve ED throughput and lessen staff injuries.

What about agitation due to alcohol intoxication?

One of the more controversial topics concerns treatment of the agitated intoxicated patient. Alcohol abuse is a common problem in the emergency department with an estimated 10-46% of visits related to alcohol-related issues.(44) There is very little evidence-based guidance for how and when to administer medication to an agitated alcohol-intoxicated patient. However, three studies conducted in the ED have each found respiratory complications with medications typically used to treat agitated patients in the emergency department.(45)(46)(47) In each study, a large proportion of patients were alcohol-intoxicated, and thus these studies may provide some evidence about optimal management. Complications with benzodiazepines were higher, though statistically non-significant, in comparison with antipsychotics. Although it is probably wise to avoid additional CNS depressant medications like benzodiazepines in alcohol-intoxicated patients, it may be that any calming medication which reduces sympathetic drive tends to predispose patients to respiratory complications.

As a consequence, recent expert guidelines have stated that medication is not first line in alcohol-intoxicated patients.(6) As a first step, external stimuli should be reduced and verbal de-escalation techniques should be utilized. If medication must be administered, FGAs such as haloperidol are typically safer than IM injections of SGAs like olanzapine or ziprasidone, which have been associated with decreased oxygen saturations in alcohol-intoxicated patients.(30)(31)(32)(48)

In a 2009 review, we offered the following series of evidence-based interventions for alcohol-intoxicated patients:(1)

- All agitated intoxicated patients who can be approached safely should undergo verbal de-escalation and be placed into a dark quiet room.

- If these interventions are successful, medication becomes unnecessary. However, if medication is required, this should be offered orally if possible.

All agitated intoxicated patients who can be approached safely should undergo verbal de-escalation.

Now that the patient is calm, what sorts of tests are necessary?

In the emergency department, agitation has a wide variety of causes, including substance intoxication, substance withdrawal, electrolyte disturbances, thyroid dysfunction, brain injury, dementia or psychiatric disorders.(36)(49) Diagnoses of mental disorders in the emergency department are particularly likely, although not all of these patients were agitated.(49) This frequently creates a dilemma, as clinicians may have to treat patients before the final diagnosis is fully known.

Nonetheless, one of the initial (and important) steps in treating agitation is a provisional diagnosis of its etiology.(6) It is admittedly challenging to form a provisional diagnosis when an extremely agitated patient first presents to the ED, but providers should first try to rule out life-threatening causes of agitation with measures such as vital signs and a finger-stick glucose.(36)(51)(52) There are also a few "rules of thumb" which can help distinguish medical causes of agitation:(37)(52)

Is the patient without any previous psychiatric history?

Are there any features atypical for a psychiatric diagnosis such as fever, lethargy or confusion?

Are vitals signs abnormal? Although agitated patients can transiently present with abnormal vital signs, they should not persist.

Are the symptoms coming and going (i.e., waxing and waning)?

Does the patient drink lots of alcohol?

Has the patient recently started any new prescription medications? Any illicit drugs?

Is the patient immune-compromised?

If the answer to any of these questions is yes, consider a medical cause for the symptoms first.

|

Case Wrap-up A 23-year-old male with a past history of schizophrenia originally presented to the emergency department in the company of police after being found on the street corner threatening passersby. He is paranoid about the staff poisoning him. He is talking loudly and is too agitated to sit down in triage, but is still somewhat intermittently directable. He reports he has not been taking his psychiatric medications. After a directed but thorough history and physical, the treating physician determined that the most likely cause of the patient's agitation was his untreated psychiatric disease. His vital signs were normal, his history did not suggest other complicating medical causes, and his physical exam was normal. He was therefore quickly given 2 mg oral risperidone and 2 mg oral lorazepam, which he agreed to take after some coaxing. He was able to be calmed without IM injections or restraint, and so was able to be discharged quickly from the emergency department to follow up with his psychiatrist. He was also given a supply of his psychiatric medication, which he had run out of. |

Conclusions

Agitation is a common emergency department problem. Although many EM physicians treat all patients with IM haloperidol and lorazepam, this medication combination is considered second-line in most instances by recent expert guidelines, as it can result in increased side effects and sedation. Patients who resist IM injections must often forcefully be restrained. Forcible restraint increases staff and patient injuries, and is associated with more ED resources and longer lengths of stay.

Based on the latest consensus evidence and experimental trials, a simplified approach may be developed for agitation in the emergency department:

- Any agitated patient should be approached with safety in mind. This safety planning should start even before agitated patients arrive in the ED.

- Verbal de-escalation should be attempted in all patients.

- If agitation persists or worsens, a "show of concern" should be attempted.

- At this stage, medication should be offered based on the most likely cause of the agitation. Underlying medical problems should be treated first, as a potential pitfall is administering antipsychotics to a patient who really has an underlying medical disorder such as hypoxemia or hypoglycemia.

- Although restraints may sometimes be necessary, they should be used sparingly and only to protect the staff or patient from harm while medications are administered. Agitated patients are often hostile, and elicit similar angry feelings from staff. However, restraints should never be used as punishment.

In summary, agitation usually requires pre-planning and a team-oriented approach. Physician presence at the bedside may be helpful until a potentially violent patient is calmed.