Course Authors

Robert J. Pignolo, M.D., Ph.D.

Dr. Pignolo is Assistant Professor and Director, Ralston-Penn Clinic for Osteoporosis & Related Bone Disorders, Department of Medicine, Division of Geriatric Medicine, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA.

Within the past 12 months, Dr. Pignolo reports no commercial conflicts of interest.

Albert Einstein College of Medicine, CCME staff and interMDnet staff have nothing to disclose.

Estimated course time: 1 hour(s).

Albert Einstein College of Medicine – Montefiore Medical Center designates this enduring material activity for a maximum of 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

In support of improving patient care, this activity has been planned and implemented by Albert Einstein College of Medicine-Montefiore Medical Center and InterMDnet. Albert Einstein College of Medicine – Montefiore Medical Center is jointly accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME), the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE), and the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC), to provide continuing education for the healthcare team.

Upon completion of this Cyberounds®, you should be able to:

Distinguish between pressure ulcers and other types of skin breakdown

Discuss the risk factors and contributing etiologies for pressure ulcers

Apply the major treatment and preventative options for pressure ulcers

Manage the possible complications of pressure ulcers.

Pressure ulcers are lesions caused by unrelieved pressure that result in underlying tissue damage. They usually develop over bony prominences below the waist but they can occur anywhere (e.g., in the nares of patients with nasogastric tubes, in the corners of the mouth in patients with endotracheal tubes, between fingers in patients with rheumatoid arthritis). The prevalence of pressure ulcers in acute care hospitals is about 3-15%,(1)(2)(3)(4) in elderly post-hip fracture patients at least 33%(5) and in critical care patients as much as 50%.(6) Ten to 35% of patients admitted to nursing homes have pressure ulcers, with the rate somewhat lower in the case of long-term care residents.(7)(8)(9)(10) Pressure ulcers should be distinguished from others causes of skin breakdown.

Differential Diagnosis

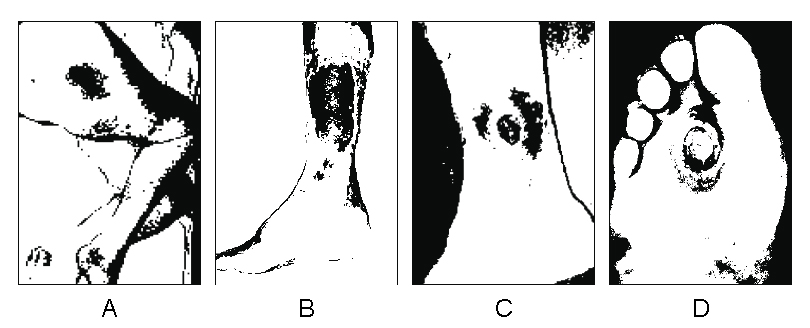

In addition to pressure ulcers, areas of skin breakdown may commonly be due to ulcers of venous insufficiency, arterial insufficiency and diabetic neuropathy (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Types of Ulcers.

Click image for larger view.

Schematic illustration of the representative shape and location of a pressure ulcer (A), venous insufficiency ulcer (B), arterial insufficiency ulcer (C), and diabetic foot ulcer.

Venous insufficiency ulcers usually occur in the lower legs, either on the pretibial areas or above the medial ankles. Although they can be the result of minor trauma and are shallow, they are often chronic and difficult to heal. Characteristic findings of venous insufficiency ulcers include pain when the foot is placed in a dependent position, location over a perforating vein or along the saphenous veins, irregular borders without undermining (i.e., continuation of the ulcer past the wound edge under the skin) and purplish coloration. They are never found above the level of the knee or in the forefoot. They may be single or multiple, and most often are tender. They usually remain superficial and exudative with granulation tissue at the base. Circumferential extension can occur if treatment is delayed.

Arterial insufficiency ulcers are painful lesions that usually occur over the ankle or other areas of the foot. Although they may be seen near bony prominences, they are distinguished from pressure ulcers by their "punched-out" or stellate appearance in the setting of diminished or absent pedal pulses, or other signs of arterial insufficiency (thin atrophic and hairless skin, diminished capillary refill or hypertrophic deformed nails). The wound base may be pale and dry with surrounding red and taut skin, or with associated eschar. Dependent rubor and increased pain with elevation may be present. They can be precipitated by trauma of the lower leg.

The diabetic ulcer occurs on the foot, usually over the metatarsal heads or on the top of toes with Charcot deformity. Repetitive injury in patients with diabetes and peripheral neuropathy precipitates the ulcer, commonly on the ball of the foot. Diabetic foot ulcers are often surrounded by thick hyperkeratosis, have undermined borders and are usually insensitive to touch.

Uncommon causes of lower extremity ulcers include connective tissue diseases (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis), other conditions associated with vasculitis, hemoglobinopathies (e.g., sickle cell disease), pyoderma gangrenosum and skin carcinoma (e.g., squamous and basal cell). High clinical suspicion should guide decisions regarding the need for ulcer biopsy in order to rule out these possibilities.

Risk Factors

Risk factors for pressure ulcers are categorized as extrinsic and intrinsic. Pressure, friction, shearing (two layers of skin sliding on each other in opposite directions) and maceration (moisture causing softening of skin) are considered extrinsic risk factors. Intrinsic factors include immobility, inactivity, fecal and urinary incontinence, malnutrition, decreased consciousness, steroid use and smoking.

Medical conditions associated with intrinsic risk factors include anemia, infection, peripheral vascular disease, edema, diabetes mellitus, stroke, dementia, delirium, alcoholism, fractures and malignancies. Age-related physiological factors such as decreased fat and muscle with which to dissipate pressure, decreased ascorbic acid levels that may cause fragility of vessels and connective tissue, fewer dermal blood vessels which may predispose to ischemic injury and declines in rates of all stages of wound healing add to the cumulative risk.

Tissue Ischemia

Tissue ischemia due to pressure is considered a major etiologic factor in the development of pressure ulcers. Constant pressure sufficient to impair local blood flow must be greater than arterial capillary pressure of 32 mm Hg to compromise perfusion and greater than venous capillary closing pressure of 8-12 mm Hg to diminish blood return. Maintained external pressure greater than two hours produces irreversible changes in animal tissues. In patients who tend to develop pressure ulcers post-operatively, there is impairment in skin blood flow over bony prominences during surgery.(11)

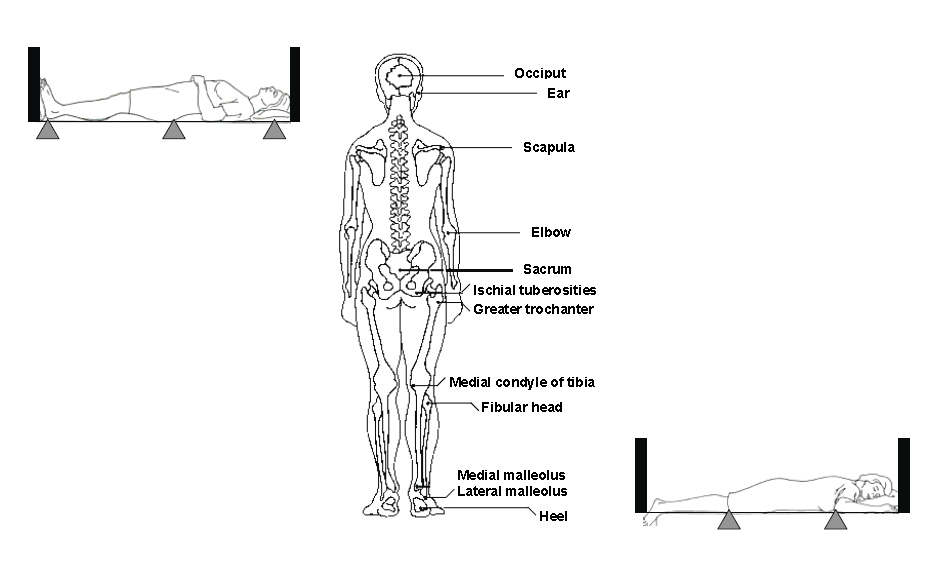

The anatomic locations of pressure points vary with position and dictate where pressure ulcers commonly occur. For example, the sacrum, heel and occiput will experience the highest pressure in the supine position, whereas the chest and knees absorb the most pressure in the prone position (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Common Pressure Ulcer Locations.

Click image for larger view.

Bony prominences where pressure ulcers occur and the most common locations (triangles) based on supine and prone positions.

In the seated position, the ischial tuberosities bear the greatest pressure. In all positions, pressure exceeds end capillary pressure.(12) Development of pressure ulcers may occur from the "inside-out" given that pathologic changes caused by pressure tend to be more severe in muscle than in skin.(13) The epidermis shows signs of necrosis late in ulcer development.(14) The implication of this pathologic sequence is that even early detection of skin breakdown may be indicative of an already established process. Factors such as hypotension, dehydration, vasomotor failure, heart failure or medications that may precipitate these states also contribute to pressure ulcer development.(6)(15)(16)(17)(18)(19)

Stages of Pressure Ulcers

The most commonly used system for staging of pressure ulcers characterizes wounds according to depth and exposure of underlying tissues,(20) and is described by the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (http://www.npuap.org/pr2.htm). Stage I ulcers are areas of non-blanchable erythema of intact skin. As a practical matter, pressure should be relieved over the area of interest before assessment. Darkly pigmented skin may not have discernable blanching but its color may differ from the adjacent area. Stage II ulcers are areas of partial-thickness skin loss (epidermis and/or dermis) presenting as an abrasion, blister or shallow crater but without evidence of bruising.

Full-thickness skin loss of subcutaneous tissue that may extend down to, but not through, underlying fascia, and which presents as a deep crater with or without undermining of adjacent tissue, constitutes a stage III ulcer. Full-thickness skin loss with extension to muscle bone, or supporting structures such as tendon or joint capsule, is diagnostic of a stage IV ulcer. Stage III and IV ulcers may also have associated undermining or tunneling/sinus tracts.

A deep tissue injury should be suspected when a purple or maroon discoloration of intact skin or blood-filled blister is present, suggesting underlying damage of tissue from pressure and/or shear. Unstageable ulcers are areas of full thickness tissue loss in which the bases of the ulcers are covered by slough and/or eschar; the true depth cannot be determined without debridement. However, dry, adherent heel eschars, without erythema or fluctuance, should be considered part of normal healing and should not be removed for staging. Illustrations with accompanying photographs of pressure ulcer stages, including examples of deep tissue injury and unstageable ulcer are available at http://www.logicalimages.com/publicHealthResources/pressureUlcer.htm.

With healing, pressure ulcers do not recapitulate the anatomic layers present prior to the onset of wound development. Healed ulcers that were once deep do not replace lost muscle, fat or dermis. Defects are filled with granulation tissue and are covered by re-epithelialization. Given this sequence, it is inappropriate to reverse stage a healing ulcer in documentation of clinical progress. For example, a stage III pressure ulcer does not with healing become a stage II or a stage I lesion; however, it is appropriate to observe and note improving characteristics in size, depth, amount of necrotic tissue and amount of exudate.

Laboratory Studies

Laboratory studies that may support underlying intrinsic risk factors that interfere with healing (e.g., albumin as a measure of under- or malnutrition) or medical conditions that may predispose to ulcers or poor healing (e.g. total lymphocyte count to assess for possible infection or malignancy) should be obtained. Routine cultures in the absence of signs and symptoms of infection are not useful. If indicated, wound culture should be performed by needle aspiration or biopsy of ulcer tissue. Bacterial counts >105/gram of tissue suggest that the ulcer will not heal without systemic antibiotics.

Prophylaxis

Pressure reduction is a major component of reducing the risk of ulcer formation.(21) Turning patients with limited mobility at least every two hours, avoiding the 90° lateral position and avoiding pressure on the ulcer have been traditionally employed measures. However, according to the American Medical Directors Association (AMDA) updated clinical practice guidelines on pressure ulcers in long-term care settings, evidence does not support that any specific timing of turning will eliminate pressure ulcers.(22)

Other measures used to reduce extrinsic contributing factors include keeping the head of the bed elevated not more than 30° except when eating, using pull sheets to move patients up in bed and keeping the heels off the bed with pillows or foam pads placed under mid-calf to ankle. When seated, sitting should be limited to less than two hours with a foam or plastic seat cushion and only with reposition at least every hour. If possible, patients should be educated to shift their weight every 15 minutes, to perform range of motion exercises to prevent contractures and to walk.

Use of appropriate support surfaces is important; however, no single support surface is effective for all situations. Static support surfaces include foam overlays (for patients whose activity is limited for short a time only) and air or water mattresses (for patients with or at risk for stage I/II ulcers). Dynamic support surfaces include alternating air mattresses (patients with/at risk for stage I/II ulcers), air-fluidized beds (patients with any stage ulcer but especially stage III/IV; difficulty with turning and transferring of patient; risk of patient and wound dehydration) and low-air-loss beds (patients with any stage ulcer but especially stage III/IV).

Static surfaces can be used on those who can change position without placing weight on the sore and on those who do not "bottom out" (i.e., make contact with) the surface beneath. Dynamic surfaces are used on those who cannot fulfill the preceding conditions and in those whose lesion is not healing. Adjunctive devices may help (e.g., sheepskin, heel and elbow protectors, trapezes). These recommendations are based on empiric considerations and scarce evidence supports the use of a specific support surface over others.(23)

To optimize moisture reduction, a thin layer of a petroleum-based product is typically used to avoid skin damage by urine or feces. Non-caking body powder may be employed to reduce friction and shearing and to absorb moisture. Incontinence should be evaluated and managed.

Nutritional support is necessary for ulcers to have an adequate chance to completely heal. An evaluation for malnutrition with subsequent initiation of high-protein, high-calorie feedings and supplements is almost always required. Vitamin C and zinc are given to patients with deficiencies.

Keys to pressure ulcer prophylaxis include the identification of risk factors and their management, as well as regular examinations of skin. The Norton or Braden Scale is often used to assess risk.(24) The Braden Scale can be viewed or downloaded at http://www2.kumc.edu/coa/education/GeriatricSkillsFair/Station4/BradenInstructionSheet.pdf. A comparison of the Norton and Braden Scales is shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Comparisons of Norton and Braden Scales for Pressure Ulcer Risk.

| Norton Scale | Braden Scale | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria |

|

|

||||||||||||||||

| Score for highest risk (total) | <14 | <12 |

Treatment

General measures in the treatment of pressure ulcers include reduction of pressure, friction, shearing and maceration. Nutrition should be optimized. The wound should be cleansed initially and with each dressing change. Infection must be treated if present.

Treatment considerations should be based on stage as well as general principles for care of any wound. Stage I pressure ulcers can be cleaned with normal saline and covered with a liquid barrier, a film dressing or a hydrocolloid dressing. Stage II ulcers can also be cleaned with normal saline. They can be covered with a film dressing, a hydrocolloid dressing, a hydrogel dressing or a moist normal saline dressing (the latter requiring more frequent changes). Stage III ulcers can be irrigated with normal saline. Necrotic tissue should be removed with mechanical, surgical or enzymatic debridement, except for a stable heel ulcer having a dry eschar. The mechanism of debridement should be chosen to minimize removal of viable tissue. Stage IV ulcers can also be irrigated with normal saline. Surgical debridement is usually performed to excise infected or necrotic tissue followed by surgical repair. Stage III and IV ulcers should be packed using materials that will promote granulation tissue and reduce exudate.

Well-established general principles of wound care should be applied to pressure ulcers. A clean wound bed should be promoted, regardless of stage, by cleansing and debridement. Keeping the wound moist helps to enhance granulation tissue. Dead space (tunnels, undermining) should be eliminated with moistened saline gauze or calcium alginate dressings. Exudate should be controlled with absorptive dressings (calcium alginate, foam or moistened gauze). Systemic antibiotics are employed only in the presence of spreading cellulitis, sepsis or osteomyelitis. A trial of topical antibiotic can be considered for clean ulcers that are not healing or are still producing exudate after 2-4 weeks of optimal therapy. Candidates for surgical repair in those able to tolerate the procedure include patients with stage IV ulcers, as well as those with severe undermining or tunneling.

Examples of commonly used dressings include transparent films (Bioclusive, Tegaderm, Op-site); foam islands (Alleyn, Lyofoam); hydrocolloids (Duoderm, Tegasorb, Replicare); petroleum-based nonadherent dressings (Vasoline gauze, Xerofoam, Adaptic); alginate (Sorbsan, Kaltostat, Algosteril, Algiderm); hydrogels (Intrasite gel, Solosite gel); and gauze packing (square 2x2 in., 4x4 in.). Little evidence supports the use of a specific dressing over alternatives, except perhaps in the case of calcium alginate.(23)

Local infection is indicated by a foul smell, greenish or copious drainage, scant granulation and dull whitish or pink base. Cellulitis is marked by erythema, warmth, swelling or tenderness. Systemic infection includes fever, elevated white count, change in mental status or increasing insulin requirement in diabetics. As part of aggressive management, identification of organisms by qualitative culture of tissue below the wound surface should be collected under sterile conditions; however, quantitative culture, expressed as colony-forming units (CFU) per gram of tissue, is most definitive. Clinical infection is almost always polymicrobial. For local infections, mechanical debridement and frequent inspection for one week may be attempted, and if no improvement occurs topical antibiotics may be tried. Cellulitis and systemic infection should be covered broadly.

Osteomyelitis should be suspected with stage IV lesions. A bone biopsy is not usually performed except as part of aggressive debridement. An elevated ESR, WBC and positive plain film (reactive bone formation, periosteal elevation), taken together, are highly specific and sensitive. MRI and indium-111 leukocyte scanning can also be used. A bone biopsy, if done, should be performed with needle aspiration through intact skin if an infected ulcer is present and radiographic evidence is positive.

For mild to moderate pain associated with pressure ulcers, NSAIDs and acetaminophen is preferable to opioids, as sedation from the latter can promote immobility. However, opioids may be necessary prior to dressing changes or debridement. Treatment of the pressure ulcer itself is the primary treatment for pain.

Limitations of Prevention and Treatment

Pressure ulcers may not be preventable, even with aggressive measures, in high-risk patients. However, a systematic approach to identify and manage pressure ulcers should be undertaken in the hospital and long-term care settings.

Development of pressure ulcers may be unavoidable with clinical conditions such as cachexia, metastatic cancer, sarcopenia, vascular compromise and terminal illness. Despite nutritional interventions, adequate intake of protein and other nutrients does not prevent pressure ulcer formation or assure healing.

Maintenance of weight as a measure of success for nutritional interventions in patients with multiple risk factors is also discouraging. According to one study, approximately 50% of nursing home residents experience at least one episode of weight loss of 5% or more of their body weight within a given 30-day period, and about 20% experience this degree of weight loss multiple times over the course of several months(25). This report also showed that weight loss of 5% or more within 30 days was associated with a greater risk of death.

As mentioned above, there is no established timing interval for pressure relief strategies (such as turning) that will affect prevention or treatment. There are no intervention strategies that consistently reduce the incidence of pressure ulcers in high-risk individuals.

Summary

Pressure ulcers are distinguished from other common causes of skin breakdown by their location over bony prominences. Multiple extrinsic and intrinsic risk factors contribute to the formation of pressure ulcers, especially in the setting of localized tissue ischemia. In 2007, the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel reviewed and redefined pressure ulcer staging to include deep tissue injury and unstageable pressure ulcers as new categories. Prophylaxis for pressure ulcers includes treatment of underlying intrinsic risk factors, if possible, and reduction of extrinsic risk factors (such as pressure) by using appropriate support surfaces. The therapeutic approach to pressure ulcers considers local treatment based on stage and general principles of wound care, as well as treatment of underlying risk factors for poor healing and formation of new ulcers.

In 2008, the American Medical Directors Association (AMDA) updated clinical practice guidelines on pressure ulcers in long-term care settings. The updated guidelines dismiss widely held beliefs regarding turning as a method of pressure relief and the notion that pressure ulcers are avoidable even in very high-risk patients.