Course Authors

Frieda Wolf, M.D.

Release Date: 10/12/2009

Upon completion of this Cyberounds®, you should be able to:

Discuss the use of gadolinium as contrast media for MRI

Assess the risk factors for developing nephrogenic systemic fibrosis when considering use of MRI in patients with renal failure

Describe the clinical presentation and biopsy findings in nephrogenic systemic fibrosis.

Rarely do we have the chance to describe a new disorder or disease. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) presents such an opportunity. Once called nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy, NSF is an acquired idiopathic disorder in patients with renal failure who develop fibrosis in skin and internal organs after exposure to gadolinium−containing contrast agents.

NSF was first noted in 1997, and published in 2000 by Cowper in the Lancet.(1) Fifteen cases of NSF were seen in 14 dialysis patients and one patient with acute tubular necrosis, who were initially thought to have scleromyxoedema. In contrast to NSF, scleromyxoedema presents with a fibrosing skin eruption, which is often associated with monoclonal gammopathy, and on biopsy demonstrates glycosaminoglycan deposition.

Epidemiology

NSF affects patients with advanced kidney disease, either stage IV or V chronic kidney disease, or acute kidney injury. Patients develop large areas of hardened skin with slightly raised plaques, papules or confluent papules, with or without pigmentary alteration. Skin biopsy must be done in order to diagnose NSF. Biopsies demonstrate increased numbers of fibroblasts, alteration of the normal pattern of collagen bundles seen in the dermis and, frequently, increased dermal deposits of mucin. Prior to 1997, gadolinium was not seen in tissue samples. Its subsequent appearance suggested that it was a new skin disorder.

The disease was first called nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy because it is characterized by thickening of the skin of extremities and trunk. When involvement of skeletal muscle, fascia, lungs, liver, testes and myocardium was noted,(2) its name was changed to nephrogenic systemic fibrosis.

NSF appeared in the late 1990s, possibly as the result of a change in clinical practice –the introduction of high−dose in gadolinium−enforced magnetic resonance angiogram (MRA) for renal failure patients. MRA was thought to be safe for these patients with renal dysfunction because it did not involve the use of iodinated contrast media, which had been known to cause contrast−induced nephropathy. Gadolinium had been in use since 1988, and higher doses were employed in order to enhance MR angiography. All reports of NSF are in patients with severe kidney dysfunction, either advanced chronic kidney disease with GFR <45 ml/min (Table 1) or acute kidney injury (Table 2.). There have been no reports of NSF with GFR better than 45 ml/min. The International NSF registry(3) at Yale has so far identified 315 cases.

Table 1. CKD Stages As Defined By K−DOQI.

| Stage | GFR ml/min |

|---|---|

| 1 | Kidney damage with GFR >90 |

| 2 | Kidney damage with GFR 60-89 |

| 3 | 30-59 |

| 4 | 15-29 |

| 5 | <15 or dialysis |

Table 2. Staging of Acute Kidney Injury.

| Stage | Serum Creatinine Criteria | Urine Output Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Increase in serum creatinine of more than or equal to 0.3 mg/dl (≥26.4 μmol/l) or increase to more than or equal to 150% to 200% (1.5- to 2-fold) from baseline | Less than 0.5 ml/kg per hour for more than 6 hours |

| 2 | Increase in serum creatinine to more than 200% to 300% (>2- to 3-fold) from baseline | Less than 0.5 ml/kg per hour for more than 12 hours |

| 3 | Increase in serum creatinine to more than 300% (>3-fold) from baseline (or serum creatinine of more than or equal to 4.0 mg/dl [≥354 μmol/l] with an acute increase of at least 0.5 mg/dl [44 μmol/l]) | Less than 0.3 ml/kg per hour for 24 hours or anuria for 12 hours |

After pre−renal and post−renal azotemia are ruled out, acute kidney injury, an abrupt reduction in kidney function, is defined as a rise in serum creatinine or a decreased in urine output, as staged above, within 48 hours.

Diagnosis

Clinical presentation of NSF must be confirmed by a skin biopsy that demonstrates fibrosis and presence of gadolinium. The most common presentation is a burning or itchy rash on the extremities and trunk, with swelling and tightening of skin. When this occurs over joints, there may be contractures because of inability to flex or extend the joints. There may or may not be hyperpigmentation or erythema. The head is very rarely involved. Some patients also complain of muscle weakness. Approximately 5% of patients have a fulminant presentation with involvement of internal organs, which in most cases is fatal.

Aside from kidney disease, other conditions that may be associated with NSF include coagulation abnormalities and deep venous thrombosis, recent surgery (particularly vascular surgery), recent failure of a transplanted kidney, and sudden onset kidney disease with severe swelling of the extremities. It is very common for the NSF patient to have undergone a vascular surgical procedure (such as revision of an AV fistula or angioplasty of a blood vessel) or to have experienced a thrombotic episode (thrombotic loss of a transplant or deep venous thrombosis) approximately two weeks before the onset of the skin changes. The overwhelming majority of cases appears two to three months after exposure to gadolinium but may begin days after exposure. There seems to be no gender or race predilection. The only prerequisite is severe kidney disease and exposure to gadolinium. The most common symptoms are listed below in Table 3.

Table 3. Most Frequent NSF Symptoms.

| % | Symptoms |

|---|---|

| 36 | Pruritus |

| 16 | Burning |

| 52 | Pain |

| 30 | Tightness |

| 25 | Swelling |

| 24 | Paresthesias |

| 34 | Joint stiffness |

Source: Cowper SE et al. Euro J of Rad 66: 2008; 191−199.

The distribution of skin lesions can be seen in Table 4. Involvement is usually symmetric and bilateral— most often with plaques, papules and nodules. Bullae, vesicular nodules or blisters may progress to plaques, which may coalesce. Hyperpigmentation and erythema are common.

Table 4. Distribution of Skin Lesions in NSF.

| % | Distribution |

|---|---|

| 85 | Lower extremities |

| 66 | Upper extremities |

| 34 | Hands |

| 24 | Feet |

| 23 | Trunk |

| 9 | Buttocks |

| 3 | Face |

Source: Cowper SE et al. Euro J of Rad 66: 2008; 191−199.

Some examples can be seen in Figures 1 and 2. Although skin involvement was the most frequent finding, visceral involvement of the gastrointestinal tract, cardiac muscles, skeletal muscle, liver, lung and testes was also noted. This small subset of patients, represented about 5% of all the cases, and their fulminant course led to death. Accelerated cardiovascular disease was found in patients who died after onset of NSF.

Figure 1. NSF: Right Upper Extremity Skin Tightening and Hardening With Erythema and Hyperpigmentation.

From Cowper SE. Nephrogenic Fibrosing Dermopathy [NFD/NSF Website]. 2001−2009. Available at http://www.icnfdr.org. Accessed 06/01/2009

Figure 2. NSF: Hyperpigmentation of Lower Extremity With Skin Thickening in Lower Extremities of Patient With NSF.

From Cowper SE. Nephrogenic Fibrosing Dermopathy [NFD/NSF Website]. 2001−2009. Available at http://www.icnfdr.org.

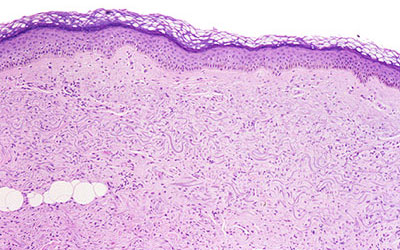

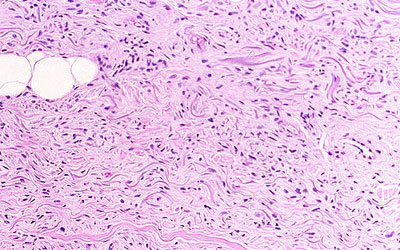

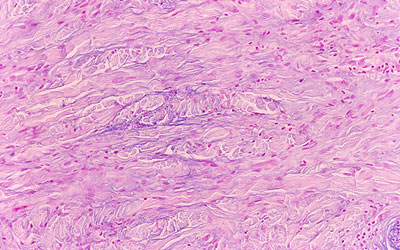

The appearance of rash, regardless of how 'typical' it is of NSF, is insufficient to establish a diagnosis. Skin biopsy must be done in order to demonstrate spindle cells and plumped collagen bundles, often with increased mucin deposition in the interstitium. The spindle cells are thought to originate from circulating fibrocytes because they are CD34/procollagen I positive cells usually involved in wound repair and tissue remodelling. These circulating fibrocytes may be stimulated by endothelial damage or tissue damage, which is why NSF is characterized as a systemic disorder. Increased expression of TGFβ−1, a stimulus for collagen I production, is also noted.(4) Examples of skin biopsy findings can be seen in Figures 3−5.

Figure 3. Skin Biopsy Showing Increased Numbers of Fibroblast−like Cells in the Dermis, Extending Into the Fascia Along Subcutaneous Septa.

From Cowper SE. Nephrogenic Fibrosing Dermopathy [NFD/NSF Website]. 2001−2009. Available at http://www.icnfdr.org.

Figure 4. Dermis Demonstrating Haphazardly Arranged Collagen Bundles and a Strikingly Increased Number of Spindled and Plump Fibroblast−like Cells.

From Cowper SE. Nephrogenic Fibrosing Dermopathy [NFD/NSF Website]. 2001−2009. Available at http://www.icnfdr.org.

Figure 5. Mucin Present and Demonstrable by the Colloidal Iron or Alcian Blue (pH 2.5) Staining Methods.

From Cowper SE. Nephrogenic Fibrosing Dermopathy [NFD/NSF Website]. 2001−2009. Available at http://www.icnfdr.org.

The presence of gadolinium should be confirmed in the dermis, in fibrotic areas of blood vessels.(5)

Pathophysiology and Risk Factors

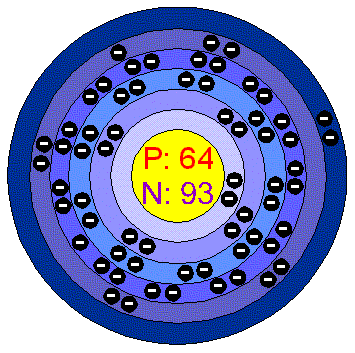

Gadolinium (Gd) is a rare earth metal, a member of the lanthanide series in the periodic table of elements (Figures 6 and 7). It was discovered in 1880 from gadolinite, an earth mineral. It has an atomic number of 64 and atomic mass of 157.25 amu. Free lanthanides are nephrotoxic. Lanthanum, the first of the series, is used to bind phosphate in patients with chronic kidney disease.

Figure 6. Gadolinium, Atomic Mass Number 64, In the Lanthanide Series.

Figure 7. Periodic Table.

Gd−containing agents are rapidly cleared, with a half−life of about two hours in people with normal renal function. When renal function is impaired, half−life can be as long as 30−120 hours. In Gadolinium−containing contrast media, the Gd binds to an organic chelating ligand, which forms a stable complex around Gd. Cyclic chelates bind Gd more tightly than linear chelates, and are more stable with much lower dissociation. Free Gd ion solubility is poor, and it may precipitate with phosphate or carbonate of hydroxyl. These precipitants are deposited in the interstitia of muscle, bone, liver and skin.

In renal failure, in addition to the reduced clearance of the Gd−containing agent, there is metabolic acidosis. In this setting, it is thought that the gadolinium−ligand complex dissociates into the metal ion and ligand. Metals such as zinc, copper and iron, or calcium and endogenous acids, compete with the ligand for binding of the gadolinium ion, causing dissociation of the complex.(6) This process is called transmetallation. Combining free gadolinium with iron, especially in dialysis patients who receive intravenous iron preparations regularly, may induce the initial tissue injury.

Approximately 100 years after its discovery, gadolinium was introduced in 1988 for use in magnetic resonance imaging. Adverse reactions included headache, nausea, pain and cold sensation at site of injection, taste preversion, dizziness, vasodilation and reduced threshold for seizures, though all these side effects were seen infrequently. It was not until 1997 that NSF was first described. Gadolinium was thought to be safe in patients with renal failure because it was not an iodinated contrast media, which were known to cause contrast−induced nephropathy, and had been used in increasing doses to enhance MR angiography, with repeated exposure in some patients.

In a study by Othersen,(7) however, repeated gadolinium exposure increased the risk of NSF by 5−10 fold, as compared with single exposure. NSF was reported with Omniscan, OptiMARK and Magnevist. It is possible that since these are the most commonly used agents and are employed in the highest doses that lack of ‘exposure’ is the reason that NSF secondary to other agents has not been reported. ProHance (gadoteridol), for example, was used for MR imaging in a study with 141 patients with advanced CKD and no cases of NSF were observed.(7) Gadoterat (Dotarem) has not been associated with NSF to date. The FDA believes that all Gd agents have the potential to cause NSF, so warning notices exist for all agents. In Europe, in particular the UK and Denmark, gadodiamide, which is associated with highest number of patients with NSF, carries a warning. The cyclic agents appear to be safer than the linear ones, or perhaps the apparent relative “safety” occurs because smaller doses of the cyclic agents are being used.

Table 5. Gadolinium−containing Contrast Media.

| Chemical Structure | Brand Name | Generic Name |

|---|---|---|

| Linear | Omniscan | Gadodiamide |

| Linear | OptiMARK | Gadoversetamide |

| Linear | Magnevist | Gadopentetic acid |

| Linear | MultiHance | Gadobenic acid |

| Linear | Primovist | Gadoxetic acid |

| Linear | Vasovist | Gadofosveset |

| Cyclic | ProHance | Gadoteridol |

| Cyclic | Gadovist | Gadobutrol |

| Cyclic | Dotarem | Gadoterat |

In looking for risk factors, other than advanced renal failure and exposure to gadolinium, the search has been confusing. Elevated anti−cardiolipin antibodies may be seen in some patients with NSF, however, these elevations also occur with increased frequency in dialysis patients. Surgical procedures are associated with NSF but most procedures were placement of vascular access for dialysis. In short, it is not possible to predict who will develop NSF and who will not.

Differential Diagnosis

Because of the nonspecific appearance of the skin and the rapid decline associated with fulminant NSF, it is important to recognize this disorder as soon as possible and to rule out diseases that look similar. The differential diagnosis includes scleromyxedema, systemic sclerosis, eosinophilic fasciitis and β2 microglobulin amyloidosis. Some clinical characteristics may differentiate NSF from these disorders but ultimately a biopsy is necessary to demonstrate the associated changes and the presence of gadolinium in the dermal vessels of patients with NSF.

Scleromyxedema often involves the face/head and is associated with monoclonal gammopathy. Both features are absent in NSF. Systemic sclerosis, usually with Raynaud’s, also involves the face and can be distinguished serologically from NSF. Eosinophilic fasciitis is a disease that typically spares hands and feet in contrast to NSF. β2 microglobulin amyloidosis is seen in chronic dialysis patients because of poor clearance of β2 microglobulin. It usually presents with arthralgias and arthropathies, and is strongly associated with carpal tunnel syndrome, bone cysts and fractures.

Treatment and Prognosis

Although some therapies have been proposed, none has cured any patient, and only a few have been able to slow the progression of NSF. These include UVA therapy, extracorporeal photopheresis,(8) cytoxan, pentoxyfilline,(9) IVIG and steroids.(10) Pentoxyfilline has anti−TNF alpha activity, and has demonstrated efficacy in other fibrotic disorders. Twelve hundred (1200) mg orally per day, with either stabilization or arrest of disease, and perhaps a slight reversal in one patient, was reported by Grobner.(9) Other reports document 1 to 3 cases. No controlled studies exist to date. A cure and complete reversal has not been reported in the literature, without restoration of kidney function.

Although the therapeutic options are slim, renal transplantation and hemodialysis (HD) do offer hope. Two or three consecutive HD sessions are required to remove Gd. In peritoneal dialysis (PD) patients, as a consequence of poor Gd clearance by PD, hemodialysis is needed to remove Gd. Immediate dialysis may be required because Gd goes to tissue where it precipitates. Optimally, dialysis should be done within two hours of exposure, prior to gadolinium precipitating in tissues. Two consecutive sessions remove up to 93% of Gd. Immediate renal transplantation is almost impossible to achieve but may be lifesaving,(11) especially for patients with the fulminant presentation.

Summary

NSF is a systemic disorder that occurs in patients with severe renal impairment. It has cutaneous manifestations that resemble other skin disorders very closely but can be differentiated in skin biopsy by typical appearance and presence of gadolinium in dermal vessels. Biopsy is crucial for diagnosis because there are few therapeutic options and because, in 5% of known cases, NSF can be fulminant and lethal.

No effective therapy exists, although restoration of renal function, for example, from transplantation may be helpful. Hemodialysis should be coordinated for the patient so that the patient receives two to three consecutive sessions, the first within two hours of exposure. Patients on peritoneal dialysis should also receive at least two hemodialysis sessions after the procedure, as PD does not remove gadolinium. The indications for the imaging procedure should be considered carefully. Gadolinium should only be used when other imaging modalities are not possible in patients with renal failure. Computerized tomography with contrast should be considered as an alternative, as well as nuclear imaging techniques. No gadolinium agent is completely safe, despite the reports of NSF in only the three most commonly used agents. Perhaps using the cyclic more stable compounds, with attention to dose, will prevent future cases of NSF, as will avoidance of unnecessary imaging procedures.