Treatment-resistant Depression in Adolescents: Assessment and Management

Course Authors

David Brent, M.D.

Dr. Brent is Academic Chief, Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, Endowed Chair in Suicide Studies and Professor of Psychiatry, Pediatrics and Epidemiology, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine

Within the past 12 months, Dr. Brent reports no commercial conflicts of interest.

Albert Einstein College of Medicine, CCME staff and interMDnet staff have nothing to disclose.

Estimated course time: 1 hour(s).

Albert Einstein College of Medicine – Montefiore Medical Center designates this enduring material activity for a maximum of 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

In support of improving patient care, this activity has been planned and implemented by Albert Einstein College of Medicine-Montefiore Medical Center and InterMDnet. Albert Einstein College of Medicine – Montefiore Medical Center is jointly accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME), the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE), and the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC), to provide continuing education for the healthcare team.

Learning Objectives

Upon completion of this Cyberounds®, you should be able to:

Provide definitions of adequate treatment and treatment-resistant depression

Present a guide to the assessment of the adolescent with treatment- resistant depression

Describe a treatment approach to the adolescent with treatment-resistant depression.

Defining Treatment−resistant Depression

We define “treatment−resistant depression” as a depression (unipolar dysthymia, major depression, or depression not otherwise specified (NOS) that has shown an inadequate clinical response to at least one evidence−based treatment with duration and dose within current clinical guidelines.(7) An “adequate clinical response” is usually defined as either a 50% or greater reduction in depressive symptoms, or a rating on the Clinical Global Impressions Improvement Subscale of “much or very much improved.”

The treatment response may be less than optimal because the initial diagnostic formulation is incorrect or incomplete.

There are three evidence−based treatments for adolescent depression: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) and interpersonal therapy (IPT). An adequate duration for all three treatments is 8−12 weeks. There are two FDA−approved medications for adolescent depression — fluoxetine (adequate dosage 20−40 mg) and escitalopram (adequate dosage 10−20 mg).

Clinical Import

Around 40% of depressed youth will not respond to initial treatment with an SSRI,(14) and even with the combination of CBT and medication, response rates at 12 weeks range between 55−71%.(12)(30) Those who do not respond to an initial treatment are at risk for developing sub−syndromal and eventually chronic depression, which is functionally impairing and associated with a higher rate of suicidal behavior.(10)(15)(35)

Assessing the Adequacy of Previous Treatment

A treatment may not have worked because it was inadequate in intensity, duration or quality. Lack of adherence to medication or psychotherapy regimens also render such a trial as less than adequate. Patients may have been adherent with treatment, but the medication or psychotherapy was not of sufficient dosage. With respect to psychotherapy, a minimum effective dosage is between 8−12 sessions. With respect to medication, the half−life of several agents such as citalopram and sertraline is much shorter in adolescents than in adults, which means some youth treated with these agents may be underdosed (see Tables 1 and 2).(2)(21) Especially if one has failed more than one trial with an SSRI, obtaining a trough plasma level of antidepressant plus metabolite is useful to determine if the patient is adherent, and also, to consider the possibility that the patient may be a rapid metabolizer who may need higher and/or more frequent dosing.

Table 1. Antidepressants: Half-Lives. 1

| Drug | Half-Life | Developmental Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Fluoxetine | 4-6 days | Higher levels in children than adults |

| Paroxetine | 11 hours | But non−linear, may be “overdosing” |

| Sertraline | 15.3-20.4 hrs. | Non-linear, lower than in adults |

| (s) Citalopram | 16.4-19.2 hrs. | Lower than in adults |

| Venlafaxine | 9-13 hrs. | Lower than in adults |

| Nefazadone | 3.9 vs. 7 hrs. | Lower than in adults |

1 Adapted from Findling RL, McNamara NK, Stansbrey RJ, Feeny NC, Young.C.M., Peric FV, Youngstrom EA. The relevance of pharmacokinetic studies in designing efficacy trials in juvenile major depression. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology 2006; 16:131-145.

Substance abuse can both mimic depression, and accompany it.

Table 2. Citalopram Pharmacokinetics: Steady State.

| Half-Life at 20 mg(hrs) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Isomer | Adolescent1 | Adult2 |

| S | 16.9 | 32.7 |

| R | 30.4 | 54.3 |

1 Perel J, Axelson D, Rudolph G, Birmaher B. Stereoselective PK/PD of s-citalopram in adolescents: Comparisons with adult findings. Clin Pharmacol Therapeutics 2001; 69:30.

2 Sidhu J, Priskorn M, Segonzac A, Grollier G, Larsen F. Steady-state pharmacokinetics of the enantiomers of citalopram and its metabolites in humans. Chirality 1997; 9:686-692.

Adequate treatment also requires sufficient duration. Data from adults suggest that it takes around four weeks to assess the impact of a given dosage of an SSRI.(33) Lack of adequate exposure (e.g., low plasma levels of drug + metabolite) has been associated with a poor response to fluoxetine and to citalopram in depressed adolescents in the TORDIA study. Also, exposure is very much dependent on dose/kg. The likelihood of response in adolescent depression treated with bupropion is correlated with the level of drug plus active metabolites.(18)

Patients with comorbid anxiety disorder may require higher doses of antidepressants and anxiety-focused psychotherapy.

If the initial treatment is reported to be one of the evidence−based therapies, the clinician should determine if treatment was of sufficient frequency and duration to have an impact. In order for psychotherapy to have been considered “adequate,” a patient should be able to explain its basic principles. Alternatively, a patient may be able to relay the key lessons imparted from a given treatment but does not implement them. It is important to understand what are the barriers preventing the use of these interventions prior to proceeding to another therapeutic strategy.

Optimization of Initial Treatment

Often, patients have shown a partial response to a given treatment. For patients who have tolerated a specific SSRI, in the absence of other factors contributing to a less than optimal response, the first choice should be to increase the dosage of the current medication.(25) If a patient has responded to psychotherapy, but is now in a “taper phase,” a brief period of more frequent sessions may be indicated.

Diagnostic Assessment

The treatment response may be less than optimal because the initial diagnostic formulation is incorrect or incomplete. Diagnostic considerations fall into four categories. The patient may have: (a) a different subtype of mood disorder requiring different interventions; (b) the wrong primary diagnosis; (c) clinically significant comorbid psychiatric diagnoses; or (d) comorbid medical illness.

Patients may have a subtype of mood disorder, namely bipolar disorder, psychotic depression, or seasonal affective disorder, for which there are specific treatments that are distinct from CBT, IPT, and SSRI’s. The index of suspicion for bipolar disorder in early onset depression should be high, especially if there is a family history or bipolarity.(4)(31) Even brief hypomanic episodes in youth may be indicative of bipolar disorder, as many youth will progress from bipolar NOS to bipolar I and II.(5) Treatment with antidepressants without use of a mood stabilizer is relatively contraindicated. Based on studies with adult depressives, patients with psychotic depression will require a combination of antidepressants and antipsychotic agents, and those with seasonal affective disorder will benefit from light therapy.

The rates of depression are increased in epilepsy, asthma, inflammatory bowel disorder, diabetes and migraine.

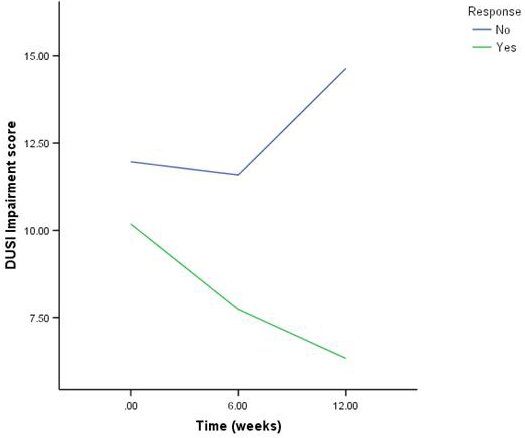

Patients may not respond to “adequate treatment” for depression because either the primary diagnosis is wrong, or another comorbid condition is contributing to non−response. For example, mood symptoms are often secondary to, or comorbid with, ADHD, substance abuse, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), anxiety or eating disorders. In those with ADHD, school and peer difficulties can lead to demoralization and depression that will only remit when the attentional issues are addressed. Substance abuse can both mimic depression, and accompany it. In either case, the mood symptoms often will not remit until the patient abstains from use. In a recent study of adolescent treatment−resistant depression, alcohol and substance use was associated with a poorer rate of response and high risk for suicidal events (see Figure 1).(11)(23)

Figure 1. Drug and Alcohol Use in Responders and Non-Responders in the TORDIA Trial.

Both anxiety and OCD lead to significant dysphoria, especially when anxious patients are unable to avoid an anxiogenic situation. Also, it is difficult to experience mastery and pleasure when anxiety symptoms lead to avoidant social behavior. Anxious patients may benefit from a higher dose of antidepressant, and psychotherapy focused on graduated exposure to anxiety provoking situations. A patient with an eating disorder may not respond to an antidepressant until nutritional status is normalized. Patients with Asperger’s syndrome often develop depression because of a sense of social isolation and inability to connect with peers, in which case, teaching social skills, and greater emotional awareness will be an important part of the treatment.

There are a number of comorbid medical conditions that can predispose to or mimic depression. Hypothyroidism, anemia and mononucleosis can all cause fatigue. The rates of depression are increased in epilepsy, asthma, inflammatory bowel disorder, diabetes and migraine. Also, treatments for epilepsy and inflammatory bowel disease may induce depression. Treatments for migraine may not help depression and vice versa, but venlafaxine and duloxetine are two agents that may have efficacy for both disorders.(20)

Although not well studied, exacerbations in chronic disorders can lead to depressive symptoms if they interfere with activities important to the individual,(28) and conversely, depression may cause the patient to be non−adherent, which in turn may lead to an exacerbation of the chronic illness. Lower levels of folic acid and vitamin B12 have been reported to be associated with depression.(16) The use of oral contraceptives is associated with lower levels of B12, and B6 deficiency, which may predispose to depression.(29)

Sleep difficulties may lead to depression, may be a symptom of depression or may be a complication of SSRI treatment.

Residual Depression and Side Effects

Episodic non−adherence to antidepressants such as sertraline, citalopram and venlafaxine can result in withdrawal effects that include flu−like symptoms, fatigue and dysphoria. On the other hand, a depressed adolescent may have shown some response to treatment but still have residual symptoms, such as fatigue, lability, irritability or sleep difficulties. Irritability may be due to inadequate treatment but if it is isolated or associated with lability, then targeting emotion regulation with psychotherapy or with mood stabilizers like lithium or an antipsychotic are reasonable approaches. While augmentation of antidepressants with antipsychotics, with lithium and with bupropion has been shown to be useful for treatment−resistant depression in adults, this has not been studied in children and adolescents.(8)(34)

When patients have residual fatigue, the clinician must rule out medical comorbidities, and also sleep difficulties that result in fatigue. Assuming that these have been eliminated, augmentation with bupropion is often helpful, as it is an activating agent. Sleep difficulties may lead to depression, may be a symptom of depression or may be a complication of SSRI treatment. If a patient complains of daytime fatigue and the timing of the fatigue fits the pharmacokinetic pattern of the antidepressant, then either splitting the dose between evening and morning, or shifting the drug to the evening may be helpful. On the other hand, in the absence of fatigue related to the drug, it is better to give antidepressants in the morning, in order to minimize sleep disruption secondary to these agents.

For those with difficulty falling, or staying asleep, a review of sleep hygiene can be useful. Also, the clinician should inquire about symptoms consistent with sleep disorders, namely parasomnias, sleep apnea, narcolepsy, and restless legs syndrome. Patients should not ingest caffeinated beverages in the afternoon. If the patient is going to bed too late, then efforts should be made to advance bedtime. Adolescents should "shut down" prior to going to sleep, and not be stimulated with phone calls, watching television or using the computer as part of their bedtime routine. Some patients have difficulty falling asleep because of anxiety or rumination, which can be targeted with psychotherapy that counters ruminative thoughts and uses relaxation techniques. Pharmacological agents for those with difficulty falling asleep include diphenhydramine and melatonin. Proper management of sleep difficulties is important because it can be an important correlate and cause of treatment resistance. In one study, the use of trazodone was associated with a particular poor treatment response(12).

Psychosocial Stressors

A number of psychosocial stressors have been associated with the onset and maintenance of depression, and may interfere with treatment response.(see Table 3).

Table 3. Psychosocial Stressors that Affect Treatment Outcome.

| Stressor | Intervention |

|---|---|

| Parental depression | Treatment of parent improves child |

| History of abuse | CBT, IPT, respond worse; need to address trauma |

| Bullying | School mandated to intervene |

| Family discord | Predicts non-response, relapse; improvement related to response |

| Sexual orientation | Bullying, family discord |

| Loss | Traumatic grief treatment |

Current parental depression has been shown to interfere with response to CBT in several studies of the treatment or prevention of depression.(13)(22)(26) Moreover, treatment of maternal depression is associated with a lower risk of onset of symptomatology in the child and a better response when the child is in treatment for mood or anxiety disorders.(38)(40) Therefore, assessment and treatment of parental depression is an important part of the management of depression in youth.

Current parental depression has been shown to interfere with response to cognitive behavioral therapy.

A history of abuse may lead to a less vigorous response to psychotherapy oriented to depression, and may require treatment that addresses issues of traumatic stress and current disorder family interaction.(1)(3) Parent−child conflict has been consistently associated with a less vigorous response to treatment as well as with relapse, so that assessment and treatment of these difficulties makes good clinical sense.(1)(6)

Youth may be being bullied at school. Schools are mandated to take action against bullying, and the clinician should help the family and patient advocate for an end to this activity. Sometimes, youth may become depressed in response to concerns about sexual orientation, which, in turn, can be a precipitant for peer bullying and parental rejection. The clinician should inquire about these issues and be prepared to work with the school, family and patient to help come to a healthier equilibrium. Patients who have lost a close friend or relative may become depressed, and these depressive episodes may be associated with complicated grief, that is, pining, preoccupation with the deceased, inability to focus on current life issues, and mental anguish and guilt in thinking about the deceased.(9) Treatment of complicated grief may require a more specialized type of psychotherapy, which may be necessary in order to facilitate recovery from the depression as well.(37)

The best way for the clinician to prevent the development of treatment resistant depression is to intervene early, since response rate is inversely related to chronicity.

The clinician should encourage the family to collaborate with the school about educational and social issues and, when necessary, should join the family in advocacy for the needs of the patient. In addition to the social issues described above, depressed youth often fall behind in their schoolwork, and feel hopelessness about ever catching up. Negotiating a “repayment plan” in which the patient may have a reduced load and a reasonable timetable for making up the work can help to reduce the stress experienced by educationally challenged depressed youth.

Preventing Treatment−resistant Depression

The best way for the clinician to prevent the development of treatment resistant depression is to intervene early, since response rate is inversely related to chronicity.(14)(17) In addition, the clinician must treat until remission, since response without remission will lead to recurrence and the development of chronic depression, which is much more difficult to treat.(34) Those who attain remission begin to show a different trajectory than non−remitters as early as four weeks after the beginning of treatment, which suggests the need to switch or augment treatments as soon as it is clear that the patient is not responding .(41) Finally, it is important to continue treatment for at least 6−12 months after the attainment of remission, as discontinuation prior to that time is associated with a greater risk for recurrence of depression.(19)

The patient and family should be helped to understand that depression is a disease that is no one’s fault, and to set reasonable expectations about the patient’s role at home and in school. The clinician should collaborate with the family and patient with respect to the choice of treatment interventions. The clinician should communicate hope to the patient and family, and that, while many patients require more than one intervention strategy, persistence does pay off. The level of hope or hopelessness that the patient is experiencing about treatment should be assessed because high hopelessness is associated with early drop−out from treatment (Brent, 1998).(13) The patient should be asked what things would make him or her feel more or less hopeful, which can guide treatment strategies and feedback to the patient about progress.

Regardless of the choice of intervention, it is vital to identify concrete, measurable and achievable goals. Depressed patients, especially those with chronic depression, are often very global and have difficulty being specific. Often depressed patients will pick as a goal, “I just want to feel better.” Instead, the type of goals that are more easily reified are connected to observable behavior: concentrating better in school, enjoying oneself more in social situations, engaging in activities that were formally fulfilling, being less irritable with other people—all based on observable behavior that has functional significance for the adolescent. It is important to measure progress with standardized scales, whether self−reported or by interview, especially for those with chronic depression who may minimize progress. For the same reason, parental input in assessing depressed youths’ response to treatment is important.

The patient and family should be helped to understand that depression is a disease that is no one's fault.

The combination of an SSRI antidepressant and CBT has been shown to result in a quicker, more complete response in some, although not all studies.(12)(24)(30) If patients want to start with mono−therapy, then the clinician should re−evaluate by six weeks, and if there has been no response, then consideration should be given to combined treatment. We recommend starting at the equivalent of 10 mg of fluoxetine for a week, and then increasing to 20 mg and re−evaluating at four weeks. If there has not been a significant improvement, then clinical guidelines and some studies recommend an increase in dose to 40 mg. It is important not to change dose or medication too quickly, as it takes around four weeks at a given dose to determine response status. On the other hand, non−responding patients should not be continued on the same treatment strategy beyond eight weeks. If we start with CBT mono−therapy, then we re−evaluate at 6−8 weeks, and if there has not been symptomatic progress, re−initiate a discussion with the family and patient about medication.

Assuming that one is able to attain remission, it is important to maintain these gains through booster sessions with a CBT therapist and with continuation at the same dosage of medication for 6−12 months after the patient first became asymptomatic.(27) Even for those who have achieved a good response on medication alone, the addition of CBT during the continuation phase resulted in a dramatically improved rate of remission and prevention of relapse.(26) In the absence of continuation therapy, the risk of recurrence or development of chronic depression is markedly increased.(19)

Partial Responders

The diagnostic assessment of partial responders follows the format outlined above: determine adherence and adequacy of treatment, and review possible psychiatric and medical comorbidity. For those who show a partial response but still have residual symptoms, the STAR*D data in adults suggest that augmentation is the most effective and best−tolerated next step.(34) If a patient has shown some improvement on a given drug, it does not make sense to lose another eight weeks by titrating a new medication that may or may not work. Augmentation in child and adolescent patients has been little studied, but in adults there are data to support the use of bupropion, T3, lithium and atypical antipsychotics as augmenting agents for treatment resistant depression.(34)

Based upon adult data and clinical experience, we augment with bupropion for those who are fatigued or have difficulty concentrating, and use lithium and neuroleptics for those with mood lability and irritability. One additional benefit of neuroleptic augmentation is that the drug can be given at night and can be helpful for those with difficulty falling or staying asleep. The downside of both lithium and neuroleptics are the short−term and long−term side effects that can have serious health consequences.

Non−responders

For patients who have not shown any response at all to an antidepressant, the Treatment of SSRI−Resistant Depression in Adolescents (TORDIA) can help guide the next treatment steps. In this 6−site, NIMH funded study, 334 depressed adolescents who had not responded to an adequate trial with an SSRI were randomized to one of four treatments: (a) switch to another SSRI; (b) switch to venlafaxine; (c) switch to another SSRI + CBT; or (d) switch to venlafaxine + CBT. The addition of CBT to either medication strategy resulted in a modest improvement in response rate after 12 weeks of treatment (55% vs. 41%). However, there was no difference in response rate between the two medication strategies (venlafaxine vs. SSRI, 48% vs. 47%).

Since the SSRI switch strategy resulted in fewer side effects, and venlafaxine was associated with a poorer response rate with high self−reported BDI and a higher rate of self−harm events in those with high baseline suicidal ideation, we conclude that the best medication step is to switch to a second SSRI antidepressant. If the person has not had a previous adequate trial of CBT, the addition of CBT to medication alone is likely to increase the response and remission rates.(12)(26)

Those who have not responded to a single treatment with an SSRI should be switched to another SSRI.

No studies have been conducted on third, fourth and fifth step treatments in adolescents with depression but, on the basis of STAR*D, switching to a wide variety of medications, augmentation strategies and either a switch or augmentation with CBT all produce fairly similar results. Buproprion has efficacy for both ADHD and depression. We use venlafaxine, in collaboration with the patient’s neurologist for the co−management of depression and migraine. Other agents that have a possible role in the management of treatment resistant depression include omega−3 fatty acids, lamotrigine, nefazadone and riluzone.(14)(32)(36) Non−pharmacological somatic treatments such as vagal nerve stimulation, transmagnetic cranial stimulation and even ECT have been little studied in adolescent depression. One case series seems to suggest that patients with psychotic or bipolar symptoms do well with ECT, whereas those with personality traits do not.(39)

Summary Recommendations

In conclusion, for the assessment and management of treatment−resistant patient, we recommend:

- Ascertain hopelessness and use education to counter it.

- Document improvement, or lack thereof, using standardized scales and clear, agreed−upon outcome parameters.

- Prepare patient and family for a possible period of trial and error in trying different agents before finding one that works.

- Establish the adequacy of, and adherence to, previous treatment.

- Assess for different subtypes of mood disorder, primary diagnoses, cormorbid psychiatric disorders and medical comorbidity.

- If possible, first optimize.

- For partial responders, consider augmentation first.

- For non−responders, add CBT and/or switch to another agent.

- Those who have not responded to a single treatment with an SSRI should be switched to another SSRI.

- Always aim for remission as the goal for treatment.

- Be persistent! Sixty−seven percent (67%) of STAR*D participants eventually achieved complete remission.