Course Authors

Renata Urban, M.D., and Jonathan S. Berek, M.D., M.S.S.

Dr. Urban is a Resident and Dr. Berek is Professor and Chair, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Stanford University Medical Center, Stanford, CA.

Within the past 12 months, Drs. Berek and Urban report no conflicts of interest or competing interests.

Albert Einstein College of Medicine, CCME staff and interMDnet staff have nothing to disclose.

Estimated course time: 1 hour(s).

Albert Einstein College of Medicine – Montefiore Medical Center designates this enduring material activity for a maximum of 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

In support of improving patient care, this activity has been planned and implemented by Albert Einstein College of Medicine-Montefiore Medical Center and InterMDnet. Albert Einstein College of Medicine – Montefiore Medical Center is jointly accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME), the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE), and the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC), to provide continuing education for the healthcare team.

Upon completion of this Cyberounds®, you should be able to:

Discuss the symptoms and signs associated with ovarian cancer

Discuss the staging and surgical management of epithelial ovarian cancer

Discuss common medical treatments and complications in epithelial ovarian cancer.

Ovarian cancer is the most lethal of all the gynecologic malignancies. It is an extremely challenging illness for practitioners, patients and families. The majority of ovarian tumors originate from the ovarian epithelium. Screening methods, such as the use of transvaginal ultrasonography and serum CA-125, have not been found to be effective. At the time of diagnosis, the majority of patients present with vague symptoms despite having advanced disease. The principal treatment for ovarian cancer is surgical removal of all visible tumor. The first-line chemotherapy for epithelial ovarian tumors is a regimen of carboplatin and paclitaxel. Patients with advanced disease may be treated with either intravenous or intraperitoneal chemotherapy.

Epidemiology

Ovarian cancer is the fifth-highest cause of death from solid tumors in American women. A woman's lifetime risk of developing ovarian cancer is approximately 1 in 70.(1) In 2006, it was estimated that 20,180 women were diagnosed with ovarian cancer, and 15,310 women died from the disease.(2) Approximately 90% of ovarian tumors are tissues that are derived from the coelomic epithelium, and composed of epithelial cells. The majority of epithelial ovarian malignancies are serous; other histologic types include mucinous, endometrioid, clear cell, Brenner and undifferentiated tumors. Additional ovarian tumors include sex cord stromal cell, germ cell and other rare histologies.

The majority of epithelial ovarian tumors occur in women between the ages of 56 and 60. Nearly 30% of ovarian masses in postmenopausal women are malignant, compared with 7% of those in women of reproductive age.(3) Ovarian cancer has been associated with low parity and infertility.(4) Additionally, early age at menarche and late age at menopause have been found to increase the risk of ovarian cancer.(5)

There has been controversy regarding whether fertility-stimulating drugs may increase the risk of ovarian cancer, though multiple studies have shown that infertility drugs do not increase the risk of ovarian cancer.(6)(7)(8) However, a prior meta-analysis of case-control studies showed that infertility of greater than five years, in the absence of treatment, was associated with an increased relative risk of ovarian cancer.(8) Oral contraceptive use is protective against the development of ovarian cancer, with the benefit persisting for as long as 15 years after discontinuation of the medication.(9)

Recently, obesity has been found to be associated with an increased risk for ovarian cancer.(10)(11) A meta-analysis published in 2007 demonstrated a relative risk of 1.3 for the development of ovarian cancer in obese females.(11)

Nearly 90% of ovarian tumors are spontaneous; however, 5-10% of ovarian malignancies are found in association with hereditary mutations.(12) Most hereditary ovarian tumors are associated with the BRCA-1 gene, with a smaller proportion of inherited tumors traced to the BRCA-2 gene.(13) A small number of ovarian tumors occur as part of the Lynch II syndrome; such multi-site cancer syndromes commonly occur in families with Hereditary Nonpolyposis Colon Cancer, which is associated with colon, endometrial and other cancers.

The BRCA-1 and BRCA-2 mutations are autosomal dominant disorders, and have been found to occur more frequently in women of Ashkenazi Jewish descent. Women who carry the BRCA-1 mutation have been estimated to have a lifetime risk for ovarian cancer between 28-44%, and for those women with a BRCA-2 mutation, the risk has been estimated as high as 27%.(14) In patients with a mutation in either the BRCA-1 or BRCA-2 gene, the use of oral contraceptives seems to have a protective effect.(15) Furthermore, a recent study demonstrated that in 1,828 patients with a BRCA-1 or BRCA-2 mutation, the performance of a prophylactic bilateral salpingooophorectomy was associated with an overall reduction in cancer risk of 80%.(16)

Diagnosis and Screening

The majority of patients with ovarian cancer report symptoms prior to their diagnosis; unfortunately, these symptoms are often vague and nonspecific. A survey of 1,725 women with ovarian cancer in 2000 revealed that 95% of patients had symptoms prior to their diagnosis; interestingly, 89% of patients with early stage disease reported symptoms.(17) A prospective study in 2004 demonstrated that bloating, urinary symptoms and increased abdominal size were associated with the development of ovarian cancer.(18) Urinary frequency or constipation may be due to compression of the bladder or rectum by an ovarian mass. In advanced stage disease, symptoms are frequently related to the presence of ascites, as well as bowel and omental metastases; such symptoms can include abdominal distension, nausea, anorexia or early satiety. In a retrospective study of more than 16,000 women in California, patients reported a collection of "target symptoms," including abdominal pain and bloating, for more than six months prior to the diagnosis.(19) A recent case-control study of 149 women developed a symptoms index based on the presence of pelvic and/or abdominal pain, increased abdominal size/bloating, difficulty eating, and early satiety. When these symptoms occurred more than 12 days a month for less than a year, the index had a sensitivity of 56.7% for early-stage disease and 79.5% for advanced-stage disease.(20)

One of the most important signs of ovarian cancer is the presence of a pelvic mass on physical examination, which includes a bimanual and rectovaginal examination. A mass that is solid, irregularly shaped or fixed in the pelvis is suspicious for cancer. Additionally, if an upper abdominal mass or ascites is present, the diagnosis of ovarian cancer is almost certain. However, the utility of the physical examination in the discrimination of ovarian cancer can be limited, especially in obese females.(21)

In a patient with an adnexal mass, an ultrasound is useful in the preoperative evaluation. Transvaginal ultrasonography is preferable to transabdominal because of improved visualization of the adnexa with transvaginal views.(22) Features of an ovarian cyst which are suspicious for malignancy include irregular borders, echogenic material within the mass, and irregular septae.(23) Doppler color flow imaging may possibly improve the utility of ultrasound in the assessment of potential malignancies.(24)(25) The size of the mass does have bearing on the management. In a premenopausal female, a complex mass measuring 8 to 10 cm may initially be monitored with ultrasound. However, the mass should be surgically removed if it does not resolve within 2-3 months. In post menopausal women, a simple ovarian cyst measuring 10 cm or less may be followed conservatively;(26) however, if the cyst is larger than 10 cm or has complex features that are suggestive of malignancy, it should be surgically removed.

Figure 1. Preoperative Evaluation of the Patient with an Adnexal Mass.

Used with permission from Practical Gynecologic Oncology, Berek and Hacker

Serum CA-125 levels can help discriminate benign from malignant masses in postmenopausal women. CA-125 levels greater than 65 mU/mL provide a sensitivity of 91% for the detection of an ovarian malignancy in postmenopausal patients.(27) The sensitivity of CA-125 for the detection of ovarian cancer is estimated at 61-90%, and the specificity at 71-93%; the positive predictive value is estimated at 35-91% and the negative predictive value at 67-90%.(1)(28)(29)(30)(31) In premenopausal females however, the level of CA 125 conveys much less specificity, as it can be elevated in a number of benign conditions.

Other gynecologic conditions leading to an elevation in CA-125 include functional ovarian cysts, benign ovarian neoplasms, endometriosis, adenomyosis, leiomyoma and pelvic inflammation. CA-125 levels were found to be elevated in 1% of 888 healthy patients and 6% of 143 patients with nonmalignant disease.(32) Recent studies have examined the use of patterns of serial CA-125 levels as they pertain to the detection of ovarian cancer.(33) Several large cohort studies have found that the combined use of ultrasonography and CA-125 is useful in screening for ovarian cancer in postmenopausal women.(34)(35)

Recently, a new technique using mass spectrometry in the assessment of serum protein has been suggested as a screen for ovarian cancer. A study of 116 serum samples of patients with ovarian cancer and matched subjects found that those samples from ovarian cancer patients displayed the same cluster pattern.(36) However, further assessment of data from this study showed that this technique may not be as reliable as was initially thought.(37)(38)

In the preoperative assessment of a patient suspected to have ovarian cancer, other primary tumors, which can metastasize to the ovary, should be excluded. Any patient with evidence of intestinal obstruction or melena should undergo a colonoscopy. The presence of any symptoms of disease in the upper gastrointestinal tract should prompt a referral for endoscopy. Patients with breast masses should have bilateral mammography performed since breast cancer may metastasize and mimic primary ovarian cancer. If a patient has ascites in the absence of a pelvic mass, a CT of the abdomen and pelvic or MRI should be obtained to look for hepatic or other intraabdominal tumors.

The presence of an adnexal mass in a female patient should warrant referral to a gynecologist; however, the suspicion of an ovarian malignancy, based on preoperative ultrasound and CA-125 levels may indicate that a referral to a gynecologic oncologist is appropriate. A study of 1,491 patients in the California Cancer Registry found that treatment by a gynecologic oncologist was an important prognostic factor for women with ovarian cancer,(39) as such treatment was significantly associated with the performance of primary surgical staging and chemotherapy.

Surgical Treatment of Ovarian Cancer

Epithelial ovarian malignancies are staged according to the 2002 revised American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) and the International Federation of Gynecologic and Obstetrics (FIGO) system, which is shown below (Table 1). The FIGO staging is based on the intraoperative findings during surgical staging. The majority of patients (58-63%) who present with ovarian cancer are found to have stage III-IV disease.(40)

Table 1. FIGO Staging.

| Stage I | Growth limited to the ovaries. |

| Stage IA | Growth limited to one ovary, no ascites containing malignant cells. No tumor on the external surface, capsule intact. |

| Stage ICa | Tumor either stage IA or IB but with tumor on the surface on one or both ovaries; or with capsule ruptured; or with ascites present containing malignant cells or with positive peritoneal washings. |

| Stage II | Growth involving one or both ovaries with pelvic extension. |

| Stage IIA | Extension and/or metastases to the uterus and/or tubes. |

| Stage IIB | Extension to other pelvic tissues. |

| Stage IICa | Tumor either stage IIA or IIB, but with tumor on the surface of one or both ovaries; or with capsule(s) ruptured; or with ascites present containing malignant cells or with positive peritoneal washings. |

| Stage III | Tumor involving one or both ovaries with peritoneal implants outside the pelvis and/or positive retroperitoneal or inguinal nodes. Superficial liver metastases equals stage III. Tumor is limited to the true pelvis, but with histologically proves malignant extension to small bowel or omentum. |

| Stage IIIA | Tumor grossly limited to the true pelvis with negative nodes but with histologically confirmed microscopic seeding of abdominal peritoneal surfaces. |

| Stage IIIB | Tumor of one or both ovaries with histologically confirmed implants of abdominal peritoneal surfaces, none exceeding 2 cm in diameter. Nodes negative. |

| Stage IIIC | Abdominal implants >2 cm in diameter and/or positive retroperitoneal or inguinal nodes. |

| Stage IV | Growth involving one or both ovaries with distant metastasis. If pleural effusion is present, there must be positive cytologic test results to allot a case to stage IV. Parenchymal liver metastasis equals stage IV. |

a To evaluate the impact on prognosis of the different criteria for allotting cases to stage IC or IIC, it would be of value to know if rupture of the capsule was (a) spontaneous or (b) caused by the surgeon, and if the source of malignant cells detect was (a) peritoneal washings or (b) ascites.

The technique for surgical staging centers on optimal cytoreduction of all malignant cells. This principle is based on studies that have shown an improved outcome for patients with less than 1 cm of disease after surgical staging.(41)(42) A meta-analysis published in 2002 involving 81 studies, and nearly 7,000 patients, demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in survival with minimal volume of residual disease.

The primary surgical treatment of ovarian cancer is achieved through the following procedure:(3)

- Performance of a laparotomy

- Removal of free fluid for cytologic analysis; if no free fluid is present, washing should be obtained by placing normal saline in the pelvic cul-de-sacs and gutters

- Total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingooophorectomy

- Exploration of all intraabdominal and peritoneal surfaces, with biopsies of suspicious lesions

- Retroperitoneal assessment, including that of the pelvic and paraaortic lymph node chains with resection of clinically suspicious lymph nodes

- Palpation of the diaphragm, liver and spleen

- Omentectomy

- Appendectomy; the role of routine appendectomy is controversial, as prior studies have been inconclusive as to the incidence of metastases to the appendix. (44-45) However, appendectomy is always recommended in the presence of a mucinous ovarian tumor, as a primary appendiceal tumor may metastasize to the ovaries.

In women of reproductive age with early stage disease, a conservative approach may be undertaken, with sparing of the unaffected ovary and uterus. However, the patient should receive extensive counseling on the need for further surgery with removal of the uterus and ovary once childbearing is completed; a review of 282 ovarian cancer patients managed conservatively with the purpose of retaining fertility found that 33 patients recurred, and 16 died of the disease.(46)

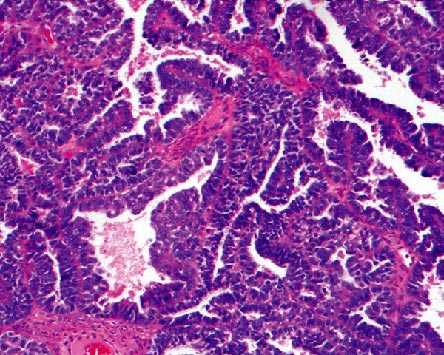

Histopathology

The majority of epithelial ovarian tumors are of serous histologic type. Other less common histologic types include mucinous, endometrioid, clear cell, Brenner and undifferentiated carcinomas. Mucinous tumors are often large in size and, more frequently, are unilateral. Endometrioid tumors are hypothesized to arise in foci of endometriosis.(47) Clear cell tumors are associated with a history of endometriosis; although they have a worse prognosis than other epithelial tumors,(48) they are treated in a similar fashion.

Borderline, or low malignant potential, epithelial tumors of the ovary represent 10-25% of all epithelial ovarian tumors. The histologic diagnosis requires the presence of atypical ovarian epithelial proliferation without stromal invasion. Borderline tumors are associated with a relatively good prognosis compared with other histologies.(49) In a series of 339 patients with borderline tumors, there was noted to be a 2% rate of progression into invasive carcinoma.(50)

Frequently, an intraoperative pathologic assessment of an ovarian mass is requested, prior to the completion of a full staging surgery. In 1991, 176 frozen sections of ovarian masses at a single institution were reviewed.(51) Sensitivity of the frozen section method for malignant or borderline disease was 83.5%. Specificity for benign lesions was 92.8%. Predictive values were computed as 100% for malignancy, 62% for borderline malignancy, and 92% for a benign disease. Diagnostic problems occurred in large borderline tumors of mucinous cell type. Eleven out of 12 false negative diagnoses were associated with sampling errors. A recent review of 914 cases revealed an overall accuracy of frozen section diagnosis of 95.3%.(52) Serous cystadenofibromas were most often misinterpreted and mistaken for borderline tumors.

Figure 2. Ovarian Serous Cystadenocarcinoma.

Used with permission from Practical Gynecologic Oncology, Berek and Hacker.

Figure 3. Well-differentiated Serous Papillary Adenocarcinoma of the Ovary.

Used with permission from Berek & Novak's Gynecology, Berek and Novak.

Treatment

Post-surgery, the current standard of care for chemotherapy for patients with epithelial ovarian cancer includes six to eight cycles of carboplatin and paclitaxel. Chemotherapy is intended for patients with early stage high-risk disease and those of higher stage of disease. High-risk factors include Grade 3 disease, clear cell histology and ascites that is positive for malignant cells. During treatment with chemotherapy, CA-125 remains a useful tumor marker in the estimation of disease responsiveness to the agents being used.(53)(54)

Table 2. Combination Chemotherapy for Advanced Epithelial Ovarian Cancer: Recommended Regimens.

| Drugs | Dose (mg/m2)* | Route | Interval (weeks) | Treatments (cycles) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Regimens | ||||

| Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy | ||||

| Paclitaxel | 135 | IV | 3, day 1 | 6 |

| Cisplatin | 50-100 | IP | day 2 | |

| Paclitaxel | 60 | IP | day 8 | |

| Intravenous Chemotherapy | ||||

| Paclitaxel | 175 | IV | 3 | 6-8 |

| Carboplatin | AUC* = 5-6 | IV | ||

| Paclitaxel | 135 | IV | 3 | 6-8 |

| Cisplatin | 75 | IV | ||

| Alternative Drugs** | ||||

| Docetaxel | 75 | IV | 3 | |

| Doxorubicin, liposomal | 35-50 | IV | 3-4 | |

| Topotecan | 1.0-1.25 | IV | 1 | |

| 4.0 | IV | 3 (daily _3 3-5 days) | ||

| Etoposide | 50 | PO | 3, days 14-21 | |

* Except for carboplatin dosing, where AUC -- area under the curve -- dose calculated by using Calvert formula

** Drugs that can be substituted for paclitaxel if hypersensitivity to that drug occurs; the number of treatments administered as tolerated.

Multiple chemotherapeutic agents are active against ovarian cancer. Regimens including platinum-based agents and taxanes have since then been found to be more effective than other combination regimens.(55)(56) The inclusion of paclitaxel with platinum compounds has been shown to produce an improvement in survival.(57) In comparison to cisplatin, carboplatin is associated with less GI side effects, as well as less nephrotoxicity, neurotoxicity and ototoxocity; it has, however, provoked more hematologic toxicities.(58)(59)

Patients who have Stage IA-IB disease without any high-risk factors, and who are completely surgically staged, do not currently require any further adjuvant therapy. In 1990, RC Young et al. published the combined results of two randomized controlled trials. Patients with Stage 1A-IB, Grade 1-2 disease were found to have equivalent survival, regardless of whether they received post-operative treatment with melphalan or not.(60)

In patients with Stage I high-risk and Stage II disease, two recent randomized controlled trials demonstrated the benefit of combination chemotherapy. In the ICON1 and ACTION trials,(61) progression-free and overall survival were significantly improved; however, the majority of these patients had not been completely surgically staged. A recent study of the Gynecologic Oncology Group examined the effects of three versus six cycles of carboplatin and paclitaxel in these patients; there was no improvement in recurrence-free survival, and there was a significant increase in toxicity.(62) At this point however, three to six cycles of chemotherapy are recommended for patients with high-risk early stage disease.

In patients with Stage III-IV disease, combination chemotherapy is more effective than single-agent regimens. Two recent studies demonstrated the efficacy of the use of six cycles of carboplatin and paclitaxel in improving the recurrence-free and overall survival of patients with advanced stage disease.(63)(64)

The possibility of intraperitoneal chemotherapy has long been advocated. Given that ovarian malignancies have a propensity to spread throughout the peritoneal cavity, intraperitoneal agents may achieve much higher concentration near tumors cells.(65) In 1996, intraperitoneal cisplatin was shown in more than 500 patients with Stage III disease to be associated with improved survival and less toxicity when compared with intravenous cisplatin.(66) A subsequent study demonstrated a significant improvement in progression-free survival in patients receiving intravenous carboplatin and paclitaxel as well as intraperitoneal cisplatin;(67) however, the associated toxicities were more significant, and the improvement in overall survival was not statistically significant. The most recent of the trials of intraperitoneal agents, GOG 172,(68) demonstrated an improvement in both progression-free and overall survival in patients who received intraperitoneal cisplatin and both intravenous and intraperitoneal paclitaxel, compared with those who received the agents only intravenously.

Intraperitoneal chemotherapy, despite its associated improvements in survival, is associated with complications related to intraperitoneal catheters, which may limit its adoption by community health centers.(68)(69) Intraperitoneal chemotherapy is currently indicated as first-line chemotherapy for patients with stage III ovarian cancer who have had optimal surgical removal of the tumor.

Conclusion

In summary, ovarian cancer remains the most lethal of the gynecologic malignancies. Epithelial ovarian cancer is the most common histologic type. Transvaginal ultrasound and serum CA-125 levels have both been extensively researched as screening methods, and are most useful in the post-menopausal population. Optimal therapy includes surgical staging and debulking, followed by chemotherapy with a platinum-based regimen and taxane.