Course Authors

Susan C. Stewart, M.D.

Dr. Stewart reports no commercial conflict of interest.

Estimated course time: 1 hour(s).

Albert Einstein College of Medicine – Montefiore Medical Center designates this enduring material activity for a maximum of 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

In support of improving patient care, this activity has been planned and implemented by Albert Einstein College of Medicine-Montefiore Medical Center and InterMDnet. Albert Einstein College of Medicine – Montefiore Medical Center is jointly accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME), the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE), and the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC), to provide continuing education for the healthcare team.

Upon completion of this Cyberounds®, you should be able to:

Introduction

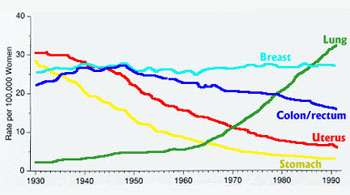

At the turn of this century, smoking by a woman was considered disgraceful behavior; there were even laws prohibiting women from smoking in public. It was not until the 1920's and 1930's when female leaders in society -- debutantes and college women -- were persuaded to smoke in public that the headlong rush to smoke began.(1) By the 1950's over 30% of the female population smoked. Many thought that women were not susceptible to smoking-related illnesses, like lung cancer, that were seen in men. What they did not realize was that men were 30 years ahead in morbidity. In 1987 the death rate from lung cancer in women surpassed that of breast cancer, the most common cancer in women, and has been steadily rising (Fig. 1).(2)

Figure 1. Cancer Death Rates* Among Women, by Cancer Site -- United States, 1930-1991.

Source: American Cancer Society.

Figures 1-4, from Husten et al, with permission.

* Rates are adjusted to the 1970 census population.

Discussion

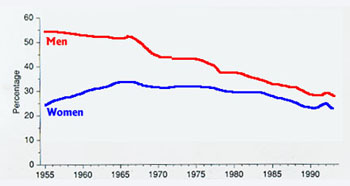

Even before the first Surgeon General's report on smoking related illnesses came out in 1964, the incidence of male smokers in this country was already going down. In the mid 1950's, close to 55% of the male population smoked; by 1993 it was 32%. On the other hand, in the mid 1950's, 25% of women smoked. The incidence actually increased to 35% in the early 1960's and then started a slow downturn, eventually paralleling males in the early 1980's (Fig. 2).

Percentage of Adults Age > 18 Years Who Are Current Cigarett Smokers,* by Sex -- United States, 1955-1993.

* Estimates since 1992 incorporate some-day smoking.

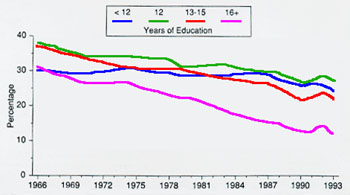

As you look at these curves I wonder whether there is a certain set percentage of the population who will, if given free access to cigarettes, become hooked. These sad statistics are reflected by surveys of smoking by youths under 18. In the early 1970's, about 16% of boys and 8 % of girls smoked. Now these percentages are nearly the same, 20-25% in both sexes. There are a few hopeful signs in this group. As opposed to the trend in the 1930's, when the more educated women led the way to the smoking habit, now college-bound young people are less likely to smoke. It is also true that the smoking incidence is lower in adults with the most years of formal education (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Percentage of Women Age > 25 Years Who Are Current Cigarette Smokers,* by Education -- United States, 1965-1993.

Source: National Health Interview Surveys, 1965-1993.

* Estimates since 1992 incorporate some-day smoking.

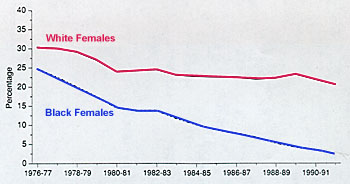

Another trend is a sharp decrease in smoking by young African-American women (Fig. 4).(2)

Figure 4. Percentage of Female High School Seniors Who Are Daily Smokers,* by Race -- United States, 1976-1992.

Of course we should do all we can to discourage the initiation of smoking in the young. In practice, however, we are confronted daily by smokers who are ill and should quit. Are there any differences between male and female smokers and do differences translate into particular ways to help women quit? Unfortunately, many of the studies of cessation are short-term and do not focus on gender differences in a way that could be helpful. Smokers themselves are a slippery group. They dive resolutely into an attempt to quit, they disappear from your schedule, and then you find they are smoking again. Three to four strong efforts to quit are usually required before long-term success is achieved.(3)

In general, the best studies have shown little difference between men and women in the characteristics of their habits or their ability to quit. Looking at women specifically, two main factors emerge. One is the tendency to medicate depression with smoking. The other is to use smoking for weight control. Another interesting observation is that in premenopausal women, those with a lot of premenstrual symptoms, are less successful quitting in the luteal phase (ovulation to menses) than in the follicular phase (menses to ovulation).(4)

Smoking and Depression

Smoking is more common in men and women with major depression and depression is twice as common in women.(3),(4) Nicotine is thought to be the main drug producing the mood elevating effect, but there may be others in tobacco smoke with similar effects. Any smoker should be evaluated for depression and treatment offered. Such treatment does not necessarily lead directly to smoking cessation but it makes quitting attempts more likely to succeed. A history of current or prior abuse may maintain the smoking habit. Smoking is private, controllable and reduces stress. Again, helping the woman address these problems may eventually enable her to quit smoking. One interesting observation is that the smoking habit itself may maintain stress. The stress perceived is actually nicotine withdrawal and smoking relieves it.(3)

Smoking and Weight Control

Ever since the advertising genius Edward Bernays thought up the motto, "Reach for a Lucky instead of a Sweet," tobacco advertising has strongly emphasized the pro-metabolic effects of nicotine. A 10% increase in metabolic rate occurs in a moderate smoker and, unless allowances are made for that at the time of cessation, weight gain will occur. More women are "supergainers" (25 lbs or more) than men.(3) The most important strategy for quitters is to see it coming. Low calorie snacks like carrot and celery stick should be always available. A graded exercise program (preceded by a stress test, if indicated) can be started. Women need to understand that "weight" is not necessarily equated with fat. Weight gain from an exercise program may be from muscle, which is a more metabolically active tissue than fat, and will raise the metabolic rate.

Another technique to use is nicotine replacement therapy. When weight gain is expected (or feared) to be a particular problem, the best choice is the nicotine gum. The reason for that is probably having a "mouth activity" that is calorie free. Using the gum successfully is a skill that has to be taught to the patient. If you are a little rusty on how to do it, take a look at the Nicotine Replacement Therapy write-up accompanying this article. The gum can now be purchased over the counter. All the more reason for us to take particular care in getting patients to use it correctly. Also, copies of a superb brochure, A Patient Guide to Nicotine Reduction Therapy, originally published by the Oregon Health Sciences University, can now be obtained for your patients through the Tobacco Intervention Network (toll free: 1-800-938-1957 or via email: kmanske9@idt.net.

Summary

Smoking by women is raising their risks of heart disease, high blood pressure, stroke and many cancers. Helping women quit must be a high preventive health priority. Addressing special risk factors and concerns, like depression and fear of weight gain, can increase your success.