Course Authors

Manuela Marinescu, M.D., and Peter Barland, M.D.

Dr. Marinescu is a Senior Rheumatology Fellow, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York.

Within the past 12 months, Dr. Marinescu reports no commercial conflicts of interest.

Estimated course time: 1 hour(s).

Albert Einstein College of Medicine – Montefiore Medical Center designates this enduring material activity for a maximum of 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

In support of improving patient care, this activity has been planned and implemented by Albert Einstein College of Medicine-Montefiore Medical Center and InterMDnet. Albert Einstein College of Medicine – Montefiore Medical Center is jointly accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME), the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE), and the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC), to provide continuing education for the healthcare team.

Upon completion of this Cyberounds®, you should be able to:

Discuss the clinical manifestations of diabetic muscular infarction (DMI)

List the diagnostic tests for DMI

Describe the purported pathogenesis of DMI

Discuss the prognosis and optimal treatment of DMI.

Recognizing the musculoskeletal manifestations of diabetes is an important component in the evaluation of patients with diabetes because the morbidity from these conditions can be very severe. Indeed, failure to make the correct diagnosis may lead to inappropriate treatment and have serious consequences.

These manifestations include diabetic amyotrophy, peripheral motor neuropathy, necrotizing fasciitis, cholesterol emboli and diabetic muscular infarction (DMI). Diabetic muscular infarction first described by Angervall and Stener in 1965(1) was a rarely reported complication of diabetes (only 116 cases reported by 2003). Prior to the availability of MRI and its application to musculoskeletal syndromes, the diagnosis of DMI could only be made by muscle biopsy, despite a fairly characteristic clinical presentation. It is likely that the incidence of DMI will be much higher now that noninvasive diagnostic tests are readily available.

Clinical Features

Diabetic muscular infarction occurs most commonly in patients with type 1 diabetes, with long duration of the disease and poor glycemic control. It is more frequent in women. There does not appear to be any age group that is predominantly affected. Most of the patients with DMI have microvascular and macrovascular target organ involvement -- nephropathy (71%), retinopathy (57%) and neuropathy (54.5%).

DMI usually affects one or a group of muscles of the thigh and can be recurrent. The typical clinical presentation of DMI is that of abrupt onset of pain in the affected muscle, accompanied by local swelling. Subsequently, there is partial pain resolution and the appearance of a palpable tender mass. The thigh muscles are most frequently affected and calf involvement was reported in only 19% of patients. The quadriceps is the most commonly affected muscle, especially the vastus lateralis and the vastus medialis. Bilateral involvement was reported in 8% of cases. In some patients the passive range of motion of the hip, knee or ankle is decreased secondary to pain. Fever and skin erythema are rather uncommon features. Only one case of DMI in a muscle of the upper limb (forearm) has been reported.

There is often a significant time-lag from the onset of symptoms until the patients seek medical advice. Among the reported cases, this delay averaged approximately 4 weeks (range 1- 40 weeks). With conservative therapy of rest and analgesics, symptoms gradually resolve over many weeks (see Treatment below). Recurrences have been reported in 48% of cases, about 9% involving the originally affected muscle and 39% involving another muscle.

Laboratory Investigations

There are no specific laboratory findings in DMI. Increased plasma levels of muscle enzymes are infrequent, with less then 50% of reported cases having high levels of creatine kinase (CK) at the time of diagnosis. The lack of correlation between muscle involvement and increased CK levels might be explained by the delay in requesting medical advice after onset of symptoms. Leukocytosis was reported in only 8% of the cases and elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate was reported in 53% of the cases.

Radiographic Findings

Standard radiographic films are rarely helpful, except to exclude bony abnormalities or soft-tissue calcifications. The most valuable diagnostic technique for DMI is MRI. Axial images are the best plane for diagnosis, although coronal and sagittal images may be useful to document the extent of involvement. The T1-weighted images show an isointense swelling of the involved muscle. Fat-suppressed T2-weighted images are consistent with diffuse heterogeneous, high signal intensity in the muscles, suggestive of edema. Specific findings on gadolinium-enhanced images are characteristic for skeletal muscle necrosis. These consist of a focal area of heterogeneous enhancement and small focal areas of rim enhancement that correspond to areas of high signal intensity on T2-weighted images (that represent infarction or necrosis within the areas of ischemic muscle).(2)

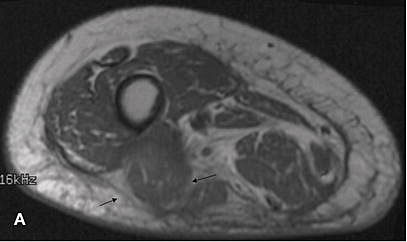

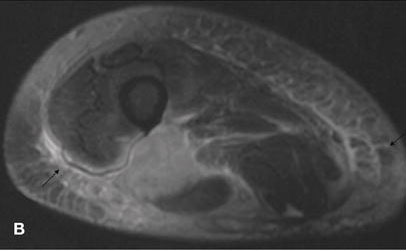

Figure 1. Fifty-four-year-old Woman with Type 1 Diabetes with 1 Week of Acute Right Thigh Pain.(4)

A. T1-weighted image in the axial plane shows slight enlargement of the short head of the biceps femoris (arrows). The signal intensity within the muscle is slightly higher than in the rest of the muscles. There is minimal loss of the fat signal within the muscle.

B. T2-weighted image in the axial plane shows heterogeneous bright signal intensity within the muscle with enlargement of the muscle. Note the subcutaneous edema (arrows).

C. and D. Coronal and axial T1-weighted images with fat suppression following the intravenous injection of gadolinium show peripheral enhancement of the mass. Note the linear, serpentine dark signal intensities within the mass (thick arrows) separated by enhancing linear signal intensities.

All images reproduced with permission from The International Skeletal Society.

The MRI enables the exclusion of other conditions such as deep venous thrombosis, pyomyositis, and primary or secondary muscle tumors. The diagnosis of DMI can be almost certain in a longstanding diabetic patient with microvascular complications, presenting with new quadriceps pain, focal tenderness and the characteristic MRI findings.

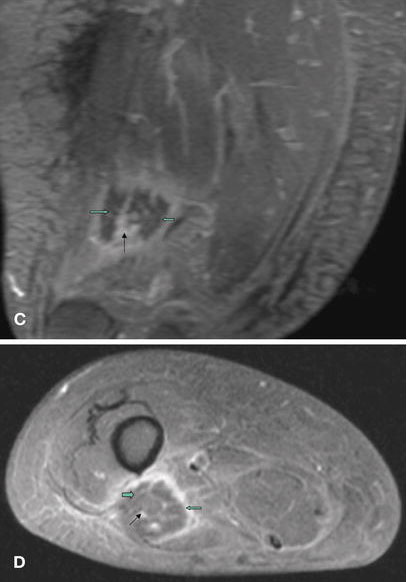

Figure 2. Fifty-year-old Man with Diabetes and Hypertension Presents with Acute Symptoms of 8 Weeks Duration.(4)

Sagittal T1-weighted image with fat saturation following the intravenous injection of gadolinium shows small, linear nonenhancing areas within the rectus femoris (thick arrows) with surrounding significant enhancement.

Histopathology

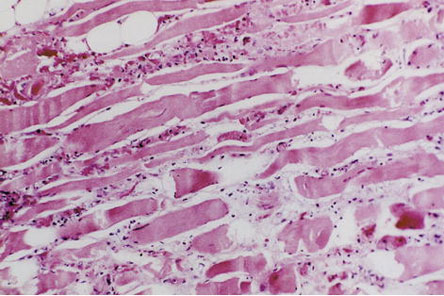

The possibility of diagnosing DMI using MRI enables physicians to avoid all invasive diagnostic methods such as excisional and incisional biopsy. Biopsy should be reserved for cases in which either the clinical presentation or the MRI findings are atypical or when appropriate treatment fails to elicit improvement. Either open biopsy or fine-needle aspiration has a good diagnostic yield. Grossly, DMI presents as a nonhemorrhagic, pale, whitish muscle. Light microscopy shows large areas of muscle necrosis and edema, phagocytosis of necrotic muscle fibers, and appearance of granulation tissue and collagen. Findings at later stages include replacement of necrotic muscle fibers by fibrous tissue, myofiber regeneration and mononuclear cell infiltration (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Necrotic Skeletal Muscle Evidenced by Nuclear Pyknosis and Dropout with Edema, Neutrophilic Infiltration, and Hemorrhage.(4)

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of DMI is not totally clarified. While arteriosclerosis and diabetic microangiopathy(5) are almost always present in patients with DMI and contribute to the muscle ischemia, it is thought that an additional insult or factor precipitates the muscle infarction -- Chester and Banker(6) proposed that there is hypoxia-reperfusion injury similar to myocardial infarction. An initial thrombotic/embolic event, which produces ischemic muscle damage, leads to an inflammatory response, hyperemia and reperfusion. This in turn leads to the generation of reactive oxygen species and muscle edema, resulting in a compartment syndrome. Both of these factors cause further muscle damage and this vicious cycle results in extensive muscle necrosis. The vulnerability of the thigh muscles may be explained, as in the heart muscle, by the high level of mechanical load sustained by this group of muscles.

Other investigators have proposed that DMI results from alterations in the coagulation-fibrinolysis system in the form of hypercoagulability. Support for this hypothesis comes from the findings of increased factor VII activity, impaired response of tissue plasminogen activator to venous occlusion, and increased plasma levels of both plasminogen activator inhibitor and thrombomodulin.(7) Further support comes from the report of two patients with DMI and antiphospholipid syndrome.(8) After their episodes of DMI, both patients showed additional evidence of coagulopathy in the setting of detectable aPL antibodies, with ocular involvement in both patients and renal involvement in one patient.

Differential Diagnosis

The disease entities that should be considered in differential diagnosis are:

- deep venous thrombosis

- polymyositis

- pyomyositis

- soft-tissue abscess

- necrotizing fasciitis

- focal myositis

- primary lymphoma of the muscle

- benign tumors or sarcomas of the muscle

- diabetic amyotrophy

- osteomyelitis

- exertional muscle rupture

- ruptured Baker's cyst

The clinical course and the MRI images are usually sufficient to make the diagnosis of DMI. Histological examination of a muscle biopsy can confirm the correct diagnosis but is often not necessary. Non-tropical pyomyositis occurs most frequently in immunocompromised patients such as those with HIV infection or in intravenous drug users. However, it has been reported in patients with diabetes.

Pyomyositis patients may have localized swelling and tenderness of a large muscle such as the quadriceps, normal or slightly elevated creatine kinase levels and elevated ESRs, similar to the findings in DMI. In contrast with DMI, these patients usually have a fever, a marked leukocytosis and the MRI with contrast shows enhanced central activity suggestive of an abscess. In pyomyositis, aspiration of the involved tender muscle yields a purulent material. Necrotizing fasciitis is usually accompanied by signs of systemic toxicity such as fever and hypotension. In addition, there is often erythema of the overlying skin, a portal of entry (cutaneous ulcer) and the area of tenderness increases rapidly in size. The MRI will show evidence of edema and inflammation of the subcutaneous tissues. Diabetic amyotrophy is characterized by pain and weakness in a lower extremity caused by a radiculopathy of a lumbar nerve root. In contrast with DMI, the pain is not localized to a circumscribed area of muscle and there are no accompanying swelling and tenderness. The MRI in diabetic amyotrophy is usually normal.

Treatment

The optimal treatment of the diabetic muscle infarction (DMI) is still debatable. There is a trend favoring conservative management (bed rest and analgesics) and medical therapy (anti-platelet drugs and/or steroids) compared to surgical therapy. Patients with either conservative or medical therapy had a significantly shorter recovery time and less recurrent events compared with surgical excision. Also there is an additional risk of postoperative complications in surgically-treated patients, including infection, hematoma and delayed wound healing. Some authors recommend avoidance of physical therapy because recovery can be prolonged,(9) but other authors have not observed this in their patients.(10)

Patients with medical management had shorter recovery times, although not statistically significant when compared with conservative therapy. Steroids may decrease edema of infarcted muscle and treat associated vasculitis as per some authors. However, vasculopathy not vasculitis is the predominant feature of DMI. If we consider the lack of significant differences in outcomes between the conservative and medical treatment groups, the risk of steroids in patients with diabetes may outweigh their benefits. It has been suggested that in patients with a hypercoagulable state such as those with antiphospholipid antibodies, anticoagulation may be the optimal treatment.(8),(10)

In the review by Kapur and McKendry,(11) the advantage of the conservative therapy was emphasized again. The time to recovery from symptom onset was 11.6, 8.5, and 18.6 weeks in the conservatively-, medically-, and surgically-treated patients, respectively. The time to recovery from treatment onset was 8.1, 5.5, and 13 weeks, respectively. The adjusted time to recovery from treatment onset in medically- versus surgically-treated patients was significant (P=0.05). The recurrence rates were 35% (9 of 26) in the conservative group, 29% (2 of 7) in the medical group, and 71% (5 of 7) in the surgery group. The mortality rates were 4% (1 of 25) in the conservative group, 14% (1 of 7) in the medical group and 29% (2 of 7) in the surgery group. These differences were not statistically significant.

Conclusions

Diabetes muscular infarction is a very rare complication of diabetes, clinically presenting with pain, swelling, and occasionally, a palpable mass.

Laboratory findings are nonspecific with CK, WBC and ESR either normal or elevated. The most valuable diagnostic technique for DMI is MRI; muscle biopsy is only indicated in cases of atypical presentation or progression of the condition.

DMI usually resolves spontaneously or after immobilization and administration of analgesics. Medical and surgical therapies are controversial. Usually, the short-term prognosis of DMI is good but the general prognosis is poor (because patients often have end-organ damage when they develop DMI).