Course Authors

Mark D. Sherman, M.D.

Dr. Sherman is the director of the Uveitis Service at Loma Linda University School of Medicine. He serves on the Board of Directors of Project Vision, Inc.

Dr. Sherman reports no commercial conflicts of interest.

Estimated course time: 1 hour(s).

Albert Einstein College of Medicine – Montefiore Medical Center designates this enduring material activity for a maximum of 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

In support of improving patient care, this activity has been planned and implemented by Albert Einstein College of Medicine-Montefiore Medical Center and InterMDnet. Albert Einstein College of Medicine – Montefiore Medical Center is jointly accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME), the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE), and the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC), to provide continuing education for the healthcare team.

Upon completion of this Cyberounds®, you should be able to:

Diagnose and classify uveitis

Conduct a systematic evaluation of uveitis patients

Discuss the relationship between uveitis and systemic medical conditions

Formulate a management plan for patients with uveitis.

Uveitis refers to inflammation of the uveal tract. By definition, the uveal tract consists of three segments, the iris, the ciliary body and the choroid. In common usage, the term uveitis has been expanded to include any condition presenting with intraocular inflammation, whether primary uveal structures are involved or secondary inflammation affects adjacent sites.

Classification

Uveitis can be classified in many ways, including location of inflammation in the eye, mode of onset and course of the disease, pathological characteristics of the inflammatory reaction, demography of the patient and underlying etiology. The more systems of classification the clinician can use, the more precisely and accurately the uveitic condition can be defined, diagnosed and treated.

Location can be divided into four general categories: anterior uveitis, intermediate uveitis, posterior uveitis and diffuse uveitis (panuveitis). Anterior uveitis includes two subcategories: iritis and iridocyclitis. Posterior uveitis includes three subcategories: retinitis, retinochoroiditis and choroiditis.

When classifying uveitis by onset and course, we separate conditions into acute, chronic, recurrent and chronic recurrent categories. Uveitis which has persisted for six weeks or more is considered chronic. Some cases may entirely resolve only to return days, weeks or months later. These are called recurrent uveitis conditions. Other cases show some resolution with treatment, but are not entirely cleared and experience exacerbations, especially with tapering of medications. These can be labeled chronic recurrent cases of uveitis.

The designation of granulomatous or nongranulomatous uveitis is somewhat incomplete in the sense that these are pathologic designations and require microscopic examination. However, we have accepted the designation of granulomatous uveitis as those cases characterized by an insidious onset with gradual decrease in visual acuity, accompanied by mutton fat keratic precipitates, posterior synechiae, cataract and possible posterior segment involvement. In contrast, nongranulomatous uveitis typically presents abruptly with a red, photophobic eye and may be accompanied by a plasmoid aqueous, posterior synechiae and decreased visual acuity. Nongranulomatous uveitis may likewise involve posterior segment structures, especially in the case of spillover of cells from the anterior chamber.

Demographic information helpful in the classification of uveitis include age, sex, ethnicity, geographic locality and other personal characteristics of the patient. Of course, an etiologic diagnosis cannot be based entirely on demographic data. However, such demographic data help to formulate a differential diagnosis and construct a "tailored" laboratory evaluation.

An etiologic diagnosis may identify the underlying causative agent or may be descriptive for a group of diseases that share common clinic features. For example, "herpes simplex retinitis" is considered an etiologic diagnosis which identifies the causative agent. On the other hand "Fuchs' heterochromic iridocyclitis" names a specific uveitis syndrome, although the causative agent is unknown.

Clinical Evaluation

History

Evaluation of the patient with uveitis begins with an extensive and systematic history. In addition to the chief complaint, the clinician must obtain data pertaining to geographic history, family history, demographic history, personal history, history of systemic disease and history of present illness.

Geographic history relates to specific uveitic entities that are more prevalent in specific areas of the world, whether this results from genetic predisposition, environmental factors or social characteristics. Some regions of the world of particular interest are the Ohio River Valley (ocular histoplasmosis), Asia (Behcet's disease and Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome) and the Middle East (Behcet's disease).

Ocular histoplasmosis is characterized by multiple "punched out" choroidal lesions, atrophy along the perimeter of the optic nerve and a disciform macular scar. There is no associated vitreous inflammation and the disease may present bilaterally. Ocular histoplasmosis is related to exposure to the fungus Histoplasma capsulatum. Behcet's disease is a multisystem autoimmune disorder characterized by recurrent intraocular inflammation in association with oral and mucosal lesions. The incidence has been observed to follow the Silk Route of Asia and Europe. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome (VKH) is an autoimmune condition concentrated in Asia, although cases have been reported in other parts of the world as well. VKH is a multisystem disease characterized by recurrent bilateral panuveitis in association with systemic symptoms which may involve the ears, skin and meninges.

Figure 1. Major Endemic Area for Histoplasmosis in the United States (>60% of the resident population in this area is skin test positive).

Family history must cover any predisposition to collagen vascular disease, HLA-B27-related conditions (Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis, psoriatic arthritis), vasculitic disease (Behcet's disease) and hemoglobinopathies (sickle cell disease). Other points to consider in family history would be family members with particular infectious conditions such as tuberculosis.

Demographic data are especially important in constructing a differential diagnosis. For example, the age of the patient may point in the direction of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis or toxocariasis. Similarly, the sex of the patient may increase the probability of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (female) or ankylosing spondylitis (male) in children. Of course, a diagnosis cannot be made purely on demographic data but must be combined with other clinical information and laboratory evaluation.

Personal history must include inquiry regarding pets (toxoplasmosis, Bartonella and toxocariasis), diet (eating undercooked meats), sexual history (syphilis, Reiter's disease, AIDS), drug use (HIV-related disease), exposures (tuberculosis) and travel to areas known to be endemic for certain types of uveitis (e.g., Lyme disease).

Past medical history should include any history of systemic disease, with special attention to conditions such as sarcoidosis, collagen vascular disease, cancer and AIDS. Likewise, patients should be questioned regarding use of any medications for these conditions or others in the past.

In obtaining the history of present illness, patients are questioned regarding any previous uveitis attacks and the use of any topical medications. They are asked to describe the features of the onset of the current episode of inflammation including any preceding events, symptoms and previous treatments. A past ocular history is also important and should include any history of eye trauma (no matter how long ago), as well as conditions such as macular degeneration, glaucoma and previous eye surgeries.

The most important symptoms pertaining to uveitis are pain, redness, photophobia and decreased vision. Sometimes decreased vision may be characterized as hazy, cloudy, loss of central vision or distortion.

Signs of Uveitis

Examination of the uveitis patient should follow a systematic progression from the front of the eye to the back of the eye so that no clinical sign is unnoticed. Examination begins with measurement of visual acuity, which includes best corrected vision by manifest refraction in each eye. Intraocular pressure must be measured in each eye, even when uveitis involves only one eye.

The time of tonometry measurement is worth noting, especially if the patient has a history of glaucoma. External examination begins with a general assessment of periocular structures, specifically to identify alopecia, vitiligo and mucosal lesions. Orbital infiltration, proptosis, ptosis, lacrimal enlargement and conjunctival lesions should be noted and photographed if possible.

Slit lamp examination is performed to assess both the tarsal and bulbar conjunctiva, as well as anterior segment structures. Particular attention should be directed to the presence of perilimbal hyperemia (i.e., increased redness at the location where the sclera meets the cornea), corneal edema, keratic precipitates (inflammatory cells deposited on the corneal endothelium), anterior chamber cells and flare, iris nodules, iris neovascularization, posterior or anterior synechiae (adhesions between the iris at the pupillary margin and the anterior lens capsule or between the peripheral iris and corneal endothelium), heterochromia irides (a difference in iris color between the two eyes) and cataract formation.

Figure 2. Lacrimal Gland Enlargement in a Patient with Sarcoidosis.

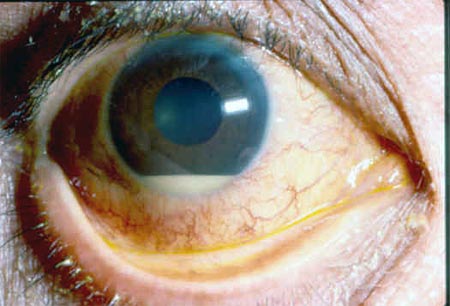

Figure 3. Hypopyon Uveitis - A Common Presentation of HLA B27-related Uveitis.

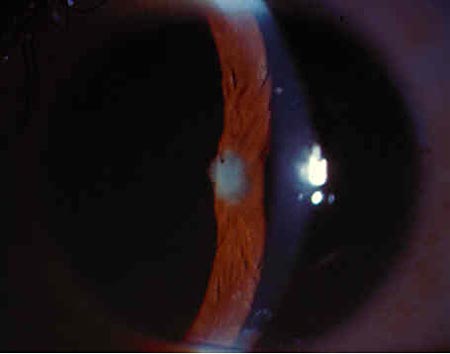

Figure 4. Extensive Posterior Synechiae and Advanced Cataract in a Patient with Sarcoidosis.

Examination of the posterior segment is performed following dilation. Particular attention is directed to the presence of vitreous cells, snowball opacities in the vitreous and snow banking along the pars plana. Optic nerve edema and macular edema must be noted. Abnormalities in the vasculature, including neovascularization and mass lesions, must be identified.

Figure 5. Toxoplasma Retinochoroiditis.

Differential Diagnosis

At the conclusion of the clinical examination, a differential diagnosis can be constructed based on a "name and mesh" strategy described and applied to uveitis by Dr. Robert Nozik.(6) Based on a thorough history and precise clinical examination, a "fabric" of positive and negative clinical features can be organized into a set of possible clinical entities known to cause similar disease patterns. This strategy of processing a differential diagnosis allows rapid and concise communication with colleagues. This strategy also leads to formulation of a tailored approach to laboratory testing. As an example, at the conclusion of a thorough uveitis consultation, and prior to laboratory testing, a clinician should be capable of communicating an entire picture of a patient's disease, such as "I have a patient who is a 40-year-old Caucasian male, presenting with acute, recurrent nongranulomatous iridocyclitis involving only the right eye and he also has a medical history of lower back pain." A differential diagnosis can then be formulated, and laboratory testing can be performed to confirm the differential diagnosis.

Laboratory Evaluation

The principles of laboratory testing for uveitis are simple. The laboratory serves the purpose of confirming a diagnosis. It is not used for formulating a differential diagnosis. Tests should not be chosen randomly, hoping for a "positive" result to give the diagnosis. Tests should not be ordered unless the clinician already knows how a positive result will be managed. Sensitivity and specificity for these specific tests should be generally understood in order to choose the most useful tests.

A "tailored approach," which tests specifically for entities in the differential diagnosis, should be chosen. This may include skin tests for tuberculosis, radiologic tests such as chest x-ray, gallium scan, chest CT scan and "sacroiliac joint imaging," as well as serologic tests such as angiotensin-converting enzyme, lysozyme, syphilis serologies, HLA testing and countless other serologic assays for infectious and noninfectious diseases. Under certain circumstances, more sophisticated imaging of the eye may be necessary, such as fluorescein angiography, ocular coherence tomography (OCT) and ocular ultrasonography. Finally, biopsy procedures may be necessary when traditional laboratory and imaging procedures have not identified an etiologic diagnosis.(1),(5) This may include conjunctival biopsy when a conjunctival mass or granuloma is seen, or vitreous or aqueous biopsy to rule out rare infectious or neoplastic conditions.

Uveitis Treatment

Treatment of uveitis consists of a variety of specific and nonspecific modalities, depending on the underlying diagnosis. Medications, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, steroids, mydriatics, cycloplegics, immunosuppressive agents and immunomodulating agents, are commonly used. Newer modalities of treatment, including oral tolerance and genetic engineering, are on the horizon.(1) The spectrum of antimicrobial agents continues to expand and infectious etiologies are more easily identified with the newest molecular techniques such as polymerase chain reaction testing of intraocular fluids.

Delivery of pharmaceutical agents may be topical, subconjunctival, posterior subtenons, oral, intravenous and intravitreal, depending on the agent and the disease under consideration. Surgical treatment may be directed to the primary disease or secondary complications. The most frequently used topical agents for the reduction of inflammation involving the anterior segment of the eye are prednisolone acetate, prednisolone phosphate and topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents. Mydriatic drops are used to prevent and reduce posterior synechiae and consist of short-acting mydriatics (tropicamide) or longer-acting mydriatics such as atropine and homatropine.

Topical medications may be needed to reduce intraocular pressure in patients with uveitic glaucoma. These medications include beta blockers, carbonic and hydrase inhibitors, and alpha agonists. Periocular steroids are occasionally required for higher dose or sustained delivery of medication. More recently, intravitreal delivery of steroids has been proposed for treatment of uveitis involving the posterior segment.

For those cases not responding to local treatment, systemic therapy may be necessary. Systemic medications include oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents and oral steroids. There is increasing recognition of the side effects of chronic systemic steroids and awareness that other immunosuppressive agents may be more desirable for long-term treatment. Thus, antimetabolites and alkylating agents have become part of the armamentarium for the treatment of severe and chronic uveitis. Most recently, the tumor necrosis factor antagonists have been shown to have efficacy for the treatment of uveitis and offer an alternative to long-term systemic steroids and other immunosuppressive agents.(2)

Summary

The field of uveitis diagnosis and treatment has grown exponentially during the past ten years. We now enjoy a greater understanding of the epidemiology of uveitis, expanded recognition of the differential diagnoses underlying uveitis and the development of improved technology for evaluation of the eye. We have also benefited from improved technology in the realm of laboratory diagnosis and from newer treatment modalities that offer more specificity and less potential toxicity to the body as a whole.