Course Authors

Meggan Mackay, M.D., M.S., and Peter Barland, M.D.

Dr. Mackay is an Assistant Professor of Medicine at Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

Dr. Mackay reports no conflict of interest. Dr. Barland reports no conflict of interest.

Estimated course time: 1 hour(s).

Albert Einstein College of Medicine – Montefiore Medical Center designates this enduring material activity for a maximum of 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

In support of improving patient care, this activity has been planned and implemented by Albert Einstein College of Medicine-Montefiore Medical Center and InterMDnet. Albert Einstein College of Medicine – Montefiore Medical Center is jointly accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME), the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE), and the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC), to provide continuing education for the healthcare team.

Upon completion of this Cyberounds®, you should be able to:

Describe the clinical manifestations and course of diffuse cutaneous scleroderma (dcSSc)

Describe the clinical manifesations and course of localized cutaneous scleroderma (CREST)

Discuss the possible pathogenesis of scleroderma as well as the current therapeutic options available for the different clinical syndromes associated with dcSSc and CREST.

Scleroderma (Systemic Sclerosis; SSc) is an autoimmune disease well known for the characteristic skin and internal organ fibrotic lesions it produces. Though descriptions of cases may be found in the writings of the ancient Greeks, Sir William Osler's description of Ssc in 1898 eloquently depicts the pathos of those suffering from this disease:

"...one of the most terrible of all human ills...to wither slowly...and be 'beaten down and marred and wasted' until one is literally a mummy, encased in an ever-shrinking, slowly contracting skin of steel, is a fate not pictured in any tragedy, ancient or modern".(1)

Though, fortunately, a rare entity, SSc has the potential for great morbidity and mortality amongst its' victims as suggested by Osler. Currently, SSc is best described as a generalized connective tissue disorder with abnormalities of three systems: the immune system, the vascular system and the extracellular matrix, resulting in extensive and exuberant fibrosis. It is important to recognize that the clinical course of scleroderma can be extremely variable. A diagnosis is not synonymous with a death sentence and the disease does not progress relentlessly in all patients. Despite ongoing research in molecular immunology and biology to unravel the pathogenic mechanisms responsible for the disease, SSc remains incurable, though certain aspects of the disease are treatable. This Cyberounds® will focus on the epidemiology, clinical presentation and course of scleroderma.

Diagnosis

Criteria set by the American College of Rheumatology in 1980 to make a diagnosis of SSc with a sensitivity of 97% and a specificity of 98%(2) require the presence of sclerodermatous skin changes in any location proximal to the metacarpal phalangeal (MCP) joints or two of the following:

- sclerodactyly

- digital pitting scars of the fingertips

- loss of digital fat pad substance

- bibasilar pulmonary fibrosis

SSc has been further divided into four subsets: Diffuse Cutaneous SSc (dcSSc), Limited Cutaneous SSc (CREST), Sine Scleroderma and scleroderma with an Overlap syndrome. We will focus only on Diffuse and Limited Cutaneous disease. Sine Scleroderma (internal organ involvement without cutaneous signs) is extremely rare and Overlap Syndromes represent different disease processes. Classification of the two major sub-groups defined by LeRoy et al. in 1980 was based primarily on the extent of skin involvement.(3) Diffuse Cutaneous SSc is characterized by the presence of skin thickness on the upper arms, thighs or torso in addition to the distal extremities and face (Figures 1, 2).

Figure 1. Diffuse Cutaneous Scleroderma.

Note the taught, shiny skin over the face and chest with characteristic hypopigmentation and pursed lips.

Figure 2. Diffuse Cutaneous Scleroderma.

Extensive cutaneous involvement of the back.

Limited Cutaneous SSc [also known as CREST (Calcinosis, Raynaud's syndrome, Esophageal dysmotility, Sclerodactyly, Telangectasias)] has skin thickening on the face and distal to the elbows and knees (Figure 3).

Figure 3. CREST Syndrome.

In addition to the tightened, shiny skin over the face, there are diffuse telangectasias and a small oral aperture.

The classification into the two subsets has tremendous implications in terms of disease mortality and morbidity as reflected by internal organ involvement. DcSSc tends to be a more aggressive disease with an increased number of systemic signs and symptoms at disease onset compared to the limited variant. In general, the patients with dcSSc will present with Raynaud's beginning within one year prior to the onset of skin changes (edematous or thickened skin - especially of the hands), fatigue, arthritis/arthralgias and tendon friction rubs. These patients with dcSSc will have higher incidences of pulmonary, renal, GI and cardiac involvement.(4) Patients with CREST may have Raynaud's for years prior to the onset of skin changes and have significantly less internal organ involvement with the exception of isolated pulmonary hypertension that occurs late in the disease process.(5)

This difference in organ involvement translates directly to a difference in mortality rates between the two subsets: a five-year mortality rate of approximately 30-40% in dcSSc vs. 20% in CREST.(6),(7) Anti-nuclear antibodies are found in 90-95% of patients overall. Anti-centromere antibodies are highly associated with the CREST variant and are found in 50-96% of those patients. The Scl-70 antibody (antibody to DNA topoisomerase I) is very specific for dcSSc, but is only found in approximately 20-40% of patients (less in African Americans) with diffuse disease, and has been associated with pulmonary involvement.(8) Important associations between autoantibodies and clinical disease subsets are categorized in Table 1.

Table 1. Anti-nuclear Antibodies Associated With Scleroderma.

| Anti-Nuclear Antibody Type | Sensitivity | Specifity | Clinical Associations |

| Anti-nuclear antibody by indirect immunoflurescence (ANA) | |||

| Screening test no pattern | 80-90% | Low | None |

| Nucleolar pattern | 25% White |

Mod | Pulmonary fibrosis |

| Centromere pattern | 15% | High | CREST? Pulmonary hypertension |

| Anti-nuclear Antibodies by Enzyme-linked Immunoassays (ELISA) | |||

| Anti-Topoisomerase 1 (Anti-Scl70) | 10 - 18% | High | Diffuse skin involvement |

| Anti-Centromere | 38% White |

High | CREST |

| Anti-RNA polymerase I, II, III | 20%| High |

Diffuse skin involvement |

|

| Anti-U3 RNP (fibrillarin) | 20% African-American |

High | Both limited and systemic Scleroderma, mainly in African American |

| Anti-PM-Scl | 3% | Mod | Overlap features of Scleroderma and polymyosiits |

Note that different percentages are given based on ethnicity for some of the autoantibodies.

Epidemiology

As seen in most of the autoimmune diseases, there is a female predominance in Ssc, with a female to male ratio of 3-4:1, once again highlighting the possible role of estrogens in immune tolerance. The incidence of the disease has been studied by five groups since 1973, revealing low rates of 3.7/million/year in Britain and Iceland compared to 18.7-22.8/million/year in the United States.(9),(10),(11),(12),(13) The mean age of disease onset varies depending on ethnicity. Disease onset in a Caucasian population typically occurs in the fourth and fifth decades as opposed to disease onset in a African American population that occurs in the third and fourth decades. The racial differences are quite striking. Not only is SSc more prevalent in African Americans than whites, but also the disease affects African Americans at a younger age and is almost twice as likely to be the diffuse and more aggressive sub-type.(6),(14)

The diagnosis of this disease always prompts the question "Why me?" and indeed that is an important question. Several studies have yielded only a very modest disease association with HLA haplotypes.(15) The associations are much more pronounced and significant between HLA subsets and specificities of the autoantibodies that accompany the disease.(16),(17) Other studies have reported possible associations with specific gene polymorphisms that are involved in regulation of structures in the extra-cellular matrix.(18),(19),(20),(21) Interestingly, studies of twins have found a low concordance for disease (concordance for SSc was the same for monozygotc and dizygotic twins) but a high concordance for the presence of antinuclear antibodies.(17)

These results highlight a recurring theme in autoimmune diseases that genetic susceptibility, though a prerequisite for disease, is not sufficient to account for disease development. Several investigators have researched the theory that microchimerism, whereby fetal cells cross the placenta during pregnancy and give rise to a graft versus host type of disease many years later following an environmental trigger, may lead to SSc.(22),(23) Though this is an intriguing theory, there is not enough evidence to implicate a direct cause and effect relationship between microchimerism and SSc.

It is generally felt that the disease is triggered by an environmental insult to the susceptible host. The nature of that insult is not clear despite epidemiological studies implicating exposures to organic solvents, silica dust and silicone implants.(24),(25),(26) There is compelling evidence for microbial agents and molecular mimicry leading to SSc in that homologies have been reported between antigenic epitopes of the SSc-specific autoantibodies and viral proteins.(27),(28),(29),(30) Geographic clusters of SSc reported in England, Italy and the Choctaw Indians in Oklahoma also provide strong evidence for the "environmental trigger" theory.(31)

Disease Course

In general, the disease course will be shaped by the sub-category of SSc. Those patients with early diffuse cutaneous disease tend to have constitutional symptoms including fatigue, arthralgias (occasionally polyarthritis), weight loss, "puffy" hands and feet before or coincident with the onset of Raynaud's phenomenon (found in 75% dcSSc) and/or skin thickening. Evidence of nail bed capillary dropout [easily seen with an ophthalmoscope set at 40 diopters (Figure 4)], digital pitting (Figure 5), tendon friction rubs or tendon contractures (Figure 6) in the context of severe Raynaud's provide early proof of the diagnosis which is made entirely on clinical findings; a positive autoantibody will support but not prove your diagnosis. The progression of skin thickening is rapid in dcSSc. Skin thickening usually peaks at two to three years and then begins to recede over the subsequent years.(4)

Figure 4. Capillary Nailbed Changes.

Dilated and tortuous capillary loops with avascular areas.

Figure 5. Digital Pitting.

Note the pitting in the pads secondary to digital ischemia. There is also a telangectasia of the third digit.

Figure 6. Sclerodactyly.

Severe tightening and thickening of the skin over the hands and forearms resulting in tethered, bound skin and flexion contractures of the fingers.

Internal organ involvement is far more frequent in dcSSc than in CREST and most organ damage occurs within the first three years. As reported by Drs. Steen and Medsger, data from their cohort of 953 patients with SSc demonstrate that the majority of patients who will go on to develop internal organ involvement will do so in the first three years from disease onset. For example, of those who developed renal disease, 75% did so within three years of diagnosis while only an additional 5% developed renal involvement in the subsequent six years. Disease mortality is directly correlated with the extent of internal organ involvement. Data from the same large cohort of patients reveal survival rates of 25%, 50%, 55% and 60% at three years in patients with severe involvement of the GI tract (malabsorption), lung (interstitial fibrosis), kidney and heart respectively.(4)

Scleroderma renal crisis, previously the most feared complication of SSc, is now eminently treatable with ACE inhibition or blockade. SSc renal crisis occurs in approximately 20-25% of dcSSc patients and rapid progression of skin thickening has been the best predictor of renal involvement.(4) Patients with renal crisis typically present with the clinical findings characteristic of a hyper-rennin state including malignant hypertension, azotemia and evidence of microangiopathic hemolysis. Early diagnosis of the underlying problem and aggressive management with ACE inhibition or blockade are critical for the survival of renal function.(32)

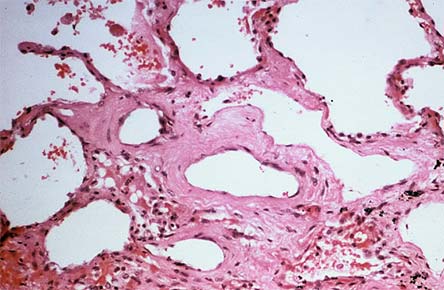

Pulmonary involvement in dcSSc is characterized as interstitial lung disease (ILD) (Figure 7) with fibrosis (22%), pulmonary hypertension (19%)or both may occur together (18%).(4) Patients with antibodies to topoisomerase -I (anti-Scl 70 antibodies) have an increased risk for developing interstitial lung disease.(33),(34)

Figure 7. Interstitial Lung Disease.

Histopathology of sclerodermatous lung revealing extensive interstitial fibrosis. The normally thin alveolar walls are almost unrecognizable.

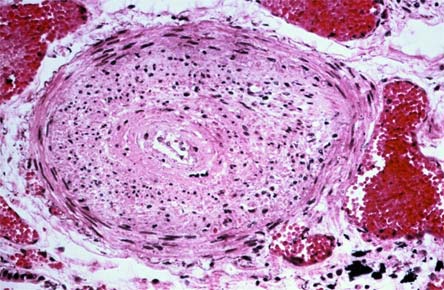

Fibrotic disease is usually preceded by an inflammatory alveolitis that is often clinically silent. The recommended practice is to perform high resolution CT and PFT's every six months for the first 3-5 years of disease to screen for pulmonary involvement. There is a potential window of opportunity for treatment with aggressive immunosuppression if there is ongoing alveolitis; once fibrosed, there is no current therapy and mortality is significantly increased. Isolated pulmonary hypertension (Figure 8) presents with progressive dyspnea and cough, a split P2, tricuspid regurgitation and right ventricular heave on exam with a reduced diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO) on pulmonary function tests and no evidence of restrictive lung disease.

Figure 8. Pulmonary Hypertension.

Cross section of a pulmonary artery revealing intimal proliferation and medial myxomatous change with a mild inflammatory infiltrate emphasizing the heterogeneity of pathologic processes in the scleroderma lung.

Gastrointestinal involvement occurs in the majority of patients. Virtually all SSc patients will have some esophageal involvement with resultant reflux disease. Some with dcSSc (8%) will go on to develop more severe involvement of the small and large intestines which may result in syndromes that include pseudo-obstruction and malabsorption that are associated with a poor outcome.(4) Though patchy myocardial fibrosis is found in most SSc patients at autopsy,(35),(36) clinically evident cardiac involvement occurs in 15% of dcSSc patients.(4) Cardiac involvement can be manifested as a "cardiac Raynaud's" with vasospasm, myocardial fibrosis with arrhythmias or pericarditis with tamponade.

CREST patients have significantly less internal organ involvement and therefore a better prognosis. Disease onset is often slowly progressive with subtle skin changes in the distal extremities preceded for years by Raynaud's. Renal crisis and interstitial lung disease are virtually unheard of in CREST, whereas isolated pulmonary hypertension appears to occur at the same rate in patients with CREST and dcSSc. The esophageal reflux disease is common in CREST but severe GI involvement with intestinal malabsorption is rare. Long-standing Raynaud's, cutaneous telangectasisas and subcutaneous calcifications are hallmarks of the disease and help to make the diagnosis. Figures 3 and 9 demonstrate the diffuse facial telangectasias characteristic of CREST.

Figure 9. CREST Syndrome.

Extensive perioral and facial telangectasias with pursed lips and mild sclerodactyly.

Depression is common in patients with SSc and has been reported in half of the patients screened for it. Given the devastating consequences of fibrosis on appearance as well as function, it is vitally important to screen for depression and to treat accordingly.(37)

Treatment Options

In most connective tissue diseases, the practice is to use immunosuppressive agents to control the abnormal immune response and lower the disease flare rate. This approach has not been successful in SSc because the pathologic mechanisms leading to the disease state are not well understood and inflammation appears to play only a minor role in the process. The fibrosis and vasculopathy that account for most of the disease morbidity may be preceded by an inflammatory infiltrate but when the disease is clinically apparent, anti-inflammatory agents are no longer effective. The exceptions would be active arthritis, pericarditis or alveolitis. Steroids, methotrexate or other immunosuppressive medications have been used to control arthritis as well as pericarditis.

Several retrospective and case-controlled studies have found some benefit (albeit modest) in aggressive treatment of alveolitis with cyclophosphamide to halt the progression of ILD.(38),(39),(40) There is currently an ongoing blinded, placebo-controlled study at the NIH addressing the efficacy of cyclophosphamide in ILD.

Pulmonary hypertension is also extremely difficult to treat. Continuous infusion of iloprost or epoprostanol has been moderately effective but prohibitively expensive and difficult to administer.(41),(42),(43) Inhaled iloprost for pulmonary hypertension is better tolerated but again only moderately effective.(44) Calcium channel blockers are only minimally effective in 25% of adults with pulmonary HTN. The recently approved Endothelin 1 receptor antagonist, Bosentan®, is extremely promising. It is given orally and two studies have demonstrated safety and efficacy.(45),(46)

Treatment of skin thickening continues to be extremely problematic. It is perhaps reassuring to inform dcSSc patients that the worst can be expected at two years. Penicillamine has been used for years but no study has demonstrated efficacy.(47) A double blind, placebo controlled trial of relaxin found no significant difference between placebo and drug.(48) Two studies have reported significant improvement in skin thickening with methotrexate.(49),(50)

One recent study has reported the successful use of intravenous urokinase but that will need to be verified.(51) Based on the theory that supplementation of some of the metalloproteinases may help to improve skin thickness, a cohort of 31 patients was treated with oral minocycline for a year and their skin scores were compared to historical controls. The study, unfortunately, did not demonstrate any efficacy of minocycline in treating the skin thickening.(52)

ACE inhibitors are critical in the treatment of SSc renal crisis. Even if patients require dialysis, they should be maintained on ACE inhibition for the anti-fibrotic and remodeling effects.

All patients with SSc should be treated with proton pump inhibitors to avoid the complications of chronic reflux disease. Small bowel hypomotility frequently gives rise to bacterial overgrowth in the gut, which can be treated with antibiotics. However, there are no current therapies for small bowel malabsorption secondary to sclerodermatous involvement of the muscularis propria other than supportive hyperalimentation.

Raynaud's phenomenon with ulceration continues to pose a treatment dilemma. Calcium channel blockers have only a modest effect on the treatment of Raynaud's.(53) Both IV and oral iloprost have also been shown to have a modest effect on the frequency and severity of Raynaud's attacks but their efficacy is limited by side effects of the medication.(54),(55)

Conclusions

Scleroderma remains a challenging and difficult disease. When counseling patients it is important to understand the differences between the disease subsets and the prognoses associated with each as well as the effects of race and sex on prognosis. The patterns of internal organ involvement have led to recommendations for the follow-up care of these patients that specifically screen for those aspects of the disease that are treatable. These include routine screening with high-resolution chest CT, echocardiography, blood pressure, PFT's, creatinine and urinalysis.

Current basic science research in SSc is making tremendous advances and is focused on understanding and preventing the fibrosis and vascular abnormalities characteristic of the disease.