Course Authors

Gary M. Gray, M.D.

Dr. Gray reports no commercial conflict of interest.

Estimated course time: 1 hour(s).

Albert Einstein College of Medicine – Montefiore Medical Center designates this enduring material activity for a maximum of 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

In support of improving patient care, this activity has been planned and implemented by Albert Einstein College of Medicine-Montefiore Medical Center and InterMDnet. Albert Einstein College of Medicine – Montefiore Medical Center is jointly accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME), the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE), and the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC), to provide continuing education for the healthcare team.

Upon completion of this Cyberounds®, you should be able to:

Describe the evolution of acute to chronic diarrhea

Evaluate, diagnose and select the initial therapy for chronic idiopathic colitis (IBD)

Discuss the emerging role of chronic infection as a cause of chronic colitis in the immunosupressed patient, especially cytomegalovirus (CMV).

Even though the causes of the inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs) remain unknown, a great deal of effort has been devoted to clinical trials of newer forms of anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressant drugs in the last fewyears. Still, when the patient presents with a distinct change in bowel habits, a careful clinical assessment remains the strongest tool for the physician in defining the category of colitis prior to selection of a therapeutic regimen. More than most GI conditions, regular surveillance for IBD in the physician's office or at the hospital bedside often provides the special insight necessary to the correct diagnosis and proper therapy.

The Patient with Increase in Frequency and Quantity of Stool Output

The normal range of stool pattern varies from one passage every other day to 2-3 per day in a particular individual. It is the change from the established norm for a particular individual that prompts concern of both the patient and physician. Patients may present to physicians after only a few days of altered bowel habits. When should an evaluation be done and what should the extent of the workup be? In general, the patient with an increase in the number and amount of stool passages without accompanying substantial fever or constitutional symptoms can be followed for a week or so before proceeding with a comprehensive evaluation.

For short-term episodes, determination of the cause is often not possible and involves considerable expense that often does not affect the outcome. Many acute enteric infections with bacteria or viruses are self-limiting and do not require drug therapy. Furthermore, therapy of some bacterial enteric infestations may prolong the course of symptoms and even promote overgrowth of Clostridium difficili, leading to prolongation of diarrhea due to the C. diff. toxin. Also, the occasional patient will acquire secondary C.diff. pseudomembranous colitis, often involving a prolonged course.

When the change in stool excretion persists for longer than seven to ten days, an evaluation is in order. Freshly collected stool should be submitted or properly preserved for analysis for ova and parasites. Bacterial culture for the usual pyogens such as Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter jejuni and special strains of E. coli is recommended. Often, the physician will need to make a formal request that the laboratory use special culture conditions for these bacteria because many microbiology labs do not routinely set up the special media required for growth of certain organisms. If persistent diarrhea is caused by one of these organisms, appropriate antibiotic or antiparasitic therapy is indicated.

Further Consideration When a Common Causative Agent Is Not Identified and Diarrhea Persists

When stool analyses are negative in theface of diarrhea that has persisted for more than one week, further evaluation is necessary. Usually, it is not advisable to administer bowel-slowing agents such as diphenoxylate-atropine (Lomotil®), loperamide (Immodium®) or tincture of opium at this stage but, instead, to examine the lower bowel. A sigmoidoscopy with a flexible fiberoptic endoscope is now done more commonly than with the rigid 25-cm instrument. When stools are completely liquid, it is preferable to carry out sigmoidoscopy without preparing the patient with enemas or an osmotic flush (with a substance such as nonabsorbable polyethylene glycol). This will allow the physician to determine whether there is loss of the delicate vascular pattern, typically seen in the normal rectum and sigmoid colon. Sites of mucosal friability, indicative of inflammatory changes of a colitis, will appear as pinpoint petechial bleeding with minimal trauma from cotton swabbing or from contact with the instrument itself. Loss of discrete smooth angular folds of mucosa due to edema produce a more linear or pipe-like appearance of the colon.

Although the recto-sigmoid exam is commonly done by gastroenterologists and surgeons, family physicians and internists can reliably perform sigmoidoscopies. However, performing a few procedures per year will not suffice; for maintenance of the proper expertise, it is important that the physician make it a routine to perform the procedures as a regular component of practice. Such facility can usually be maintained by performing screening flexible sigmoidoscopies onpatients after age 40 who have a family history of colonic polyps in parents or siblings. If an altered mucosal pattern is observed, a biopsy should be taken for histological analysis and mucosal swabs submitted for ova and parasite exam and bacterialculture.

In patients who have had prolonged, unexplained diarrhea, a biopsy may be indicated even when the gross mucosal appearance is normal because of the possibility of a microscopic colitis. In patents who are debilitated, elderly, immmunosuppressed from a disease such as AIDS or who have been taking drugs such as high dosage coriticosteriods, azathioprine or cyclosporin to maintain a transplanted bone marrow or solidorgan, stool and biopsy specimens should also be submitted for special histological analysis and culture for cytomegalovirus (CMV), cryptosporidium and cyclospora.

In the portion of patients in whom the loose stools persist in the face of a negative evaluation for an infectious cause, subacute and chronic conditions of the colon and small intestine must then be considered. Further examination of the remainder of the colon, either with a barium enema contrast X-ray series or a complete colonoscopy and a small intestinal contrast exam, may be indicated.

Colitis: The Two Inflammatory Bowel diseases (IBD's) and a New Mimicker

When the excessive stool output persists and no acute infection is identified, the inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs), ulcerative colitis (UC) and granulomatous ileo-colitis (Crohn's disease), are usually considered. Most physicians are involved in the initial evaluation and diagnosis but the therapy, often complex, usually requires the expertise of gastroenterologists and general surgeons, at least in the initial staging and initiation of therapy. An increase in the frequency and volume of stools is typical in both types of IBD and passage of blood is the rule in ulcerative colitis. However, the physician should be on the alert for typical early symptoms pointing to IBD, such as the initial constipation and blood coating of solid stool in ulcerative colitis, as well as the aggravating, constant, deep-seated, severe aching pain of active Crohn's disease, which is often described by patients as having the quality of a toothache. The "toothache" pain of Crohn's disease may occur in the absence of definite stool changes.

Role of Endoscopy and Barium-Contrast X-rays in Diagnosis of IBD

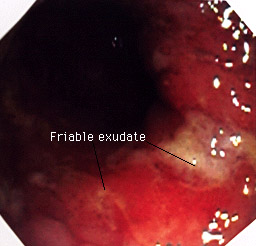

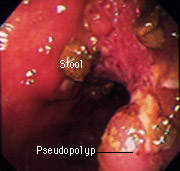

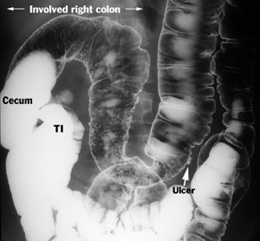

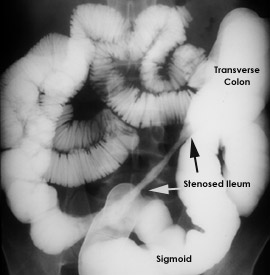

Examination of the colon by flexible endoscopy allows visual analysis and documentation with photos (Fig. 1 & 2), as well as recovery of fluid and tissue samples for ova, parasites, bacterial culture and histologic analysis. Also, the characteristic findings on barium contrast X-ray are often crucial in distinguishing between ulcerative versus Crohn's colitis (see Figures 3 & 4 and Table 1).

Figure 1. Sigmoid Colon in Ulcerative Colitis.

Enlarged folds (due to edema), spontaneous petechial bleeding (friability) and an exudate over an ulcerated area are seen 25 cm from the anal opening. More proximal areas (35 cm and above) were normal (not shown).

Courtesy of Edward Slosberg, M.D., Stanford University Medical Center.

Figure 2. Ascending Colon in Crohn's Disease.

Gross thickening of mucosa to produce polypoid projections but no significant friability. These changes were present in restricted areas ("skiplesions") of the colon with intervening normal mucosa.

Courtesy of Edward Slosberg, M.D. and Harvey Young, M.D., Gastoenterology Division, Stanford University Medical Center.

Figure 3. Undifferentiated Right-sided Colitis.

There is loss of the normal haustral scalloping in the ascending and half of the transverse colon. A barium-filled ulcer is seen at the edge of the mid-transverse colon at the site of an abrupt change to a normal pattern in more distal colonic segments. The small-diameter cecum without mucosal features and the right-sided location suggest this is probably Crohn's disease, and the patient's subsequent course verified this diagnosis. TI, terminal ileum.

Courtesy of Robert Mindelzun, M.D., Department of Radiology, StanfordUniversity Medical Center.

Figure 4. Recurrent Crohn's Disease of the Distal Ileum After Colon Resection.

The right colon and terminal ileum were resected with the margins free of disease; but, a year later, the patient developed loose stools and was found to have a narrowed segment of distal ileum proximal to the ileal-transverse colon anastamosis (progressing left to right in the figure). Note the absence of adjacent loops in the area of the featureless, narrowed ileum caused by its wall thickening. The more proximal loops of small bowel (left and upper abdomen), though somewhat dilated, appear to be normal. Because recurrence such as this is common in Crohn's disease, resection is reserved for patients with complications such as obstruction or fistulae between the diseased bowel and other organs.

Courtesy of Robert Mindelzun, M.D., Department of Radiology, Stanford University Medical Center.

Ulcerative Colitis (UC)

At the outset, most patients with UC will note only the local symptoms of lower abdominal cramping, rectal urgency and multiple passages of mucus and blood, often with scanty quantities of actual stool. The physician must ask probing questions: "How many times per day do you actually need to relieve yourself by attempting to pass a BM? What is the quantity and character of the material passed?". A stocking-like distribution of a roughened or granular mucosa is seen typically in ulcerative colitis, beginning in the rectum and extending proximally to the sigmoid. Biopsies typically reveal acute and chronic inflammation, the hallmark being the presence of segmented neutrophils in the epithelial crypts, the so-called crypt abscesses. But crypt abscesses are not always present and may be seen in some patients with Crohn's disease.

Indeed, unlike the situation with malignancies, there is no pathognomonic microscopic indicator in UC. It is important for the physician to be aware that the diagnosis can be made definitively only after infectious causes have been eliminated and when there is a constellation of symptoms, alterations in the colonic macro- and micro-anatomy, and a clear-cut response to drug therapy.

Treatment

For most patients with UC, local colonic symptoms related to the inflammation warrant regional treatment with 5-ASA enemas(1),(11) and systemic therapy with sulfasalazine orslow-release 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) preparations (Asacol®, Pentasa®).(2),(3) Systemic corticosteroid treatment should be reserved for patients who have constitutional or systemic symptoms such as anorexia, fatigue, an increased sleep requirement and weight loss. Many physicians are loath to prescribe antidiarrheal agents because of the fear of tripping off a severe attack of colitis, especially fulminant colitis and toxic megacolon. But the actual increase in risk of such a dire complication is very low and the most disturbing symptoms inactive colitis are the abdominal cramping and rectal urgency, requiring many trips to the bathroom. I recommend antidiarrheal agents routinely when patients have a colitis flare. Although the proprietary preparations such a Lomotil®) and Immodium®) are frequently prescribed, tincture of opium is considerably more effective in controlling the cramping, urgency and multiplestools.

Prognosis

UC is usually a recurrent illness and progression from seemingly localized distal colitis to global involvement of all colonic segments is not unusual. Despite the fact that many patients can be treated satisfactorily and maintained in remission for long periods of many months or years, recurrent activity and extension to other segments of colon warrant initiation of regular colonoscopic surveillance for the increased risk of cancerous change which becomes significant after eight years of disease.(4) The finding of epithelial dysplasia or the development of adenomatous polyps is a relative indication for a colectomy. Partial colectomy has no role in the treatment of UC because of the common recurrence in even a small segment of residual colon can lead to a fulminant recurrence of colitis.

Other indications for colectomy are

- a fulminant attack, with or without marked colonic gaseous distention (the so-called toxic megacolon), marked by continuing severity of the attack despite high dose intravenous corticosteroids and cyclosporin;

- perforation ofthe colonic wall with peritonitis;

- a luminal stricture that cannot be differentiated from cancer;

- severe extraintestinal complications, such as pyoderma gangrenosum, intractable arthritis and chronic inflammatory liver disease, especially sclerosing cholangitis.

Crohn's Disease

Although some patients experience rectal bleeding with Crohn's colitis, the typical history is passage of increased amounts of loose stools, with or without abdominal pain. However, a common error on the part of physicians is failing to consider Crohn's disease of the small intestine or right colon when there is only abdominal pain in the absence of diarrhea, usually localized over the involved bowel segment. Crohn's disease produces chronic inflammation of the entire bowel width, including the muscle layers, not infrequently extending to the serosa or beyond with the formation of fistulous tracts to other loops of bowel and especially to the perirectal area. Crohn's is a segmental disease, often involving portions of both small bowel and colon, and particularly of the cecum and right colon. Because of the depth of tissue involvement and the tendency to break down, substantial gross ulcerative disease and mucosal mural thickening produce appreciable distortion on both colonoscopic and radiologic examination. This serves to distinguish Crohn's from UC which involves predominantly distal colonic segments and is usually restricted to the mucosa. In Crohn's disease, surgery is often required for obstruction, entero-enteric or enterocutaneous fistulae and recurrences of the disease are the rule. Despite the curative efficacy of a colectomy in UC, surgical cure is unusual in Crohn's disease because of the strong predilection for recurrence of the granulomatous inflammation, especially at the site of ananastamosis.

Evolution of Therapy of UC and Crohn's Disease

The general physician is often reluctant to initiate systemic steroids for patients with the inflammatory bowel diseases and it is advisable to obtain the opinion of a gastroenterologist when the disease is first discovered or when the treatment proves unsatisfactory in anestablished case. As noted above, local therapy is indicated when typical symptoms of cramping abdominal pain, urgency and an increased requirement for passage of stools occur. For patients in whom the symptoms extend beyond the bowel to generalized constitutional effects, such as bodily fatigue, anorexia,increased sleep requirement, severe arthralgias or arthritis and weight loss, then systemic therapy with high-dose corticosteroids is indicated.

There are a variety of approaches to corticosteroid therapy. Short courses of 10-14 days and rapid tapering over a similar period of time are usually met with an abrupt recurrence of symptoms that is discouraging to both the physician and patient. Prednisone or prednisolone, the glucocorticoids most commonly chosen for oral administration, should be administered for at least three to four weeks, and often longer, until the patient's systemic symptoms have abated substantially. The persistence of passage of multiple stools may continue even when the patient's constitutional symptoms are under control, and the local bowel symptoms often require the addition of antidiarrheal therapy. Tapering of the steroid dosage should be slow, usually representing about 5% of the original dose on a weekly basis. Thus, it may take many weeks to lower the steroid dose and patients, not infrequently, relapse during the tapering period. Often, it is necessary to re-institute a higher steroid dosage that is about 50% of the initial level and, then,to begin tapering again two to four weeks later.

Because of this difficulty in preventing resurgence of symptoms, newer adjuvant drugs have been recommended in the last few years because they often maintain the remission and allow steroids to be discontinued. The antimetabolites 6-mercaptopurine (Purinethol®)(5) and its analog, azathioprine (Imuran®),(6) have been demonstrated to provide incremental advantage over corticosteroids alone, especially when it is difficult to taper the steroids because of continuing systemic symptoms. The onset of a beneficial effect usually requires at least 30 days and often longer--thus, the antimetabolites will need to be administered for many months and often for a year or longer. They are useful both in lowering the steroid dosage and in maintaining the remission from the colitis and the physician should seek the support of an expert in the management of patients requiring therapy with corticosteroids and other immunosuppressants.

Guidelines for therapy of the IBD's, based on the extent and severity of the disease, are provided in Table 1.

The New Common Mimicker: Cytomegalovirus (CMV) Colitis

CMV is a ubiquitous viral agent that exits in the tissues of many healthy individuals, usually in a dormant state. However, a compromise in T-cell function that occurs in AIDS, bone marrow and solid organ transplant recipients and lymphoid neoplasms sets the stage for a pathogenic spread of CMV to many organs. CMV is particularly prone to attack the lungs but an ulcerative esophagitis is well recognized and colonic involvement has now surfaced as a serious manifestation of CMV infections in the immunocompromised patient.

The widespread occurrence of AIDS and the increasing use of immunosuppressant agents in patients receiving organ transplants has facilitated the emergence of CMV as a major pathogen. CMV accounts for common opportunistic infections in AIDS, producing a colitis in as many as 10 percent of patients.(7),(11) Because the deep macroscopic ulcerations produced are usually segmental and most prominently located inthe right colon and terminal ileum, Crohn's disease is often mistakenly diagnosed, often with disastrous results if steroid therapy is initiated for presumed IBD when CMV is the actual culprit.(8) Biopsies of colonic ulcerations are indicated because Crohn's ulcers, although they may yield E. coli or Streptococcus sp. on culture, do not harbor CMV. The virus may also produce a mass effect in the colon, similar to that produced by malignant neoplasms, on Barium enema contrast X-ray or CT scan.(9)

The possible diagnosis of AIDS should be considered in the patient with newly developed segmental colitis; indeed, failure to consider AIDS as the setting for the complicating CMV colitis has resulted in patient deaths prior to the diagnosis of the primary immunosuppressive disease. CMV colitis may also develop in debilitated or immunosupressed patients without AIDS. This viral colitis has been reported in the bone marrow transplant patient,(10) in the elderly debilitated patient without the usual evidence of immunosuppression, in the patient with severe trauma(11) or bacterial sepsis and in a child with a lactalbumin milk allergy.(12)

CMV must be considered as the causative agent in the patient, in whom various defense mechanisms are compromised, who develops colonic ulcerations. Biopsies from the margins and base of the colonic ulcerative lesions reveal the typical viral inclusion bodies and the CMV can often be cultured. The polymerase chain amplification (PCR) of the viral DNA is more sensitive than culture for identification. Therapy with ganciclovir (Cytovene®) is often effective in treatment and foscarnet (Foscavir®) should be given when the patient fails to respond to ganciclovir.(13)